by Florence Ollivry

| Florence Ollivry (CC-BY-NC-SA)

Right on the corner of the eastern gate of Damascus (Bab Sharqi), on the gable of a vast building, one could once read: “Antoun Elias Mezannar textile factory, founded in the year 1890” (Mʿamal nasij, Antoun Elias Mezannar, taʿssasa sanat 1890). A century of history of silk weaving in Damascus is condensed in this place.

Antoun’s father was a weaver of bath towels (manshafa) made of silk and cotton which were manufactured on handlooms. In 1870, in Syria there were 20,000 craftsmen weaving silk on wooden, non-mechanical looms. Amongst them Antoun Mezannar soon became one of the frontrunners in the modernization of weaving techniques in Syria, and within the span of 20 years he turned his workshop into the country’s largest silk factory.

From 1840 to 1860, the Ottoman provinces of the Levant were shaken by a social unrest which spread to Damascus, where, in July 1860, the Christian quarter was violently looted and burned, many looms destroyed. This unrest became a pretext for French military intervention. The increasing intensity of trade between silk merchants in Lyon, France, and the Levant, as well as their strategic interest of their control over the Syrian silk industry, motivated the pressure they exerted on the French government to obtain the two French mandates in the Levant. Such was the hold of the Lyonese merchants’ on the Levantine sericulture (silk farming) that 90 per cent of the silks produced in Syria and Lebanon were shipped to France at that time. To facilitate this trade, French companies built a road and a railway line between Beirut and Damascus.

Lyon became the French silk capital. It was also in this city that Joseph-Marie Jacquard, who died in 1834, invented his celebrated programmable mechanical loom. At the beginning of the 20th century, Antoun Mezannar brought mechanical looms with electric motors from Lyon to Damascus and became one of the first consumers of electricity in Damascus.

| Hubert Mezannar

His youngest son, Hubert, studied at the ‘Ecole Supérieure des Industries Textiles’ in Lyon for four years, after which he and his older brother Marcel built on their father’s legacy, specializing in the production of brocade (a type of embossed or raised decoration). International competition soon developed in Damascus. The Mezannar family conducted business with a Swiss company, Rüti, which supplied them with high-performance looms. Kaiser, a draughtsman from Zurich, made sketches and designs for them. In 1936 the Mezannars were at the height of their fame and were awarded the gold medal at the trade fair in Damascus.

| Modernization of the Textile industry in Syria

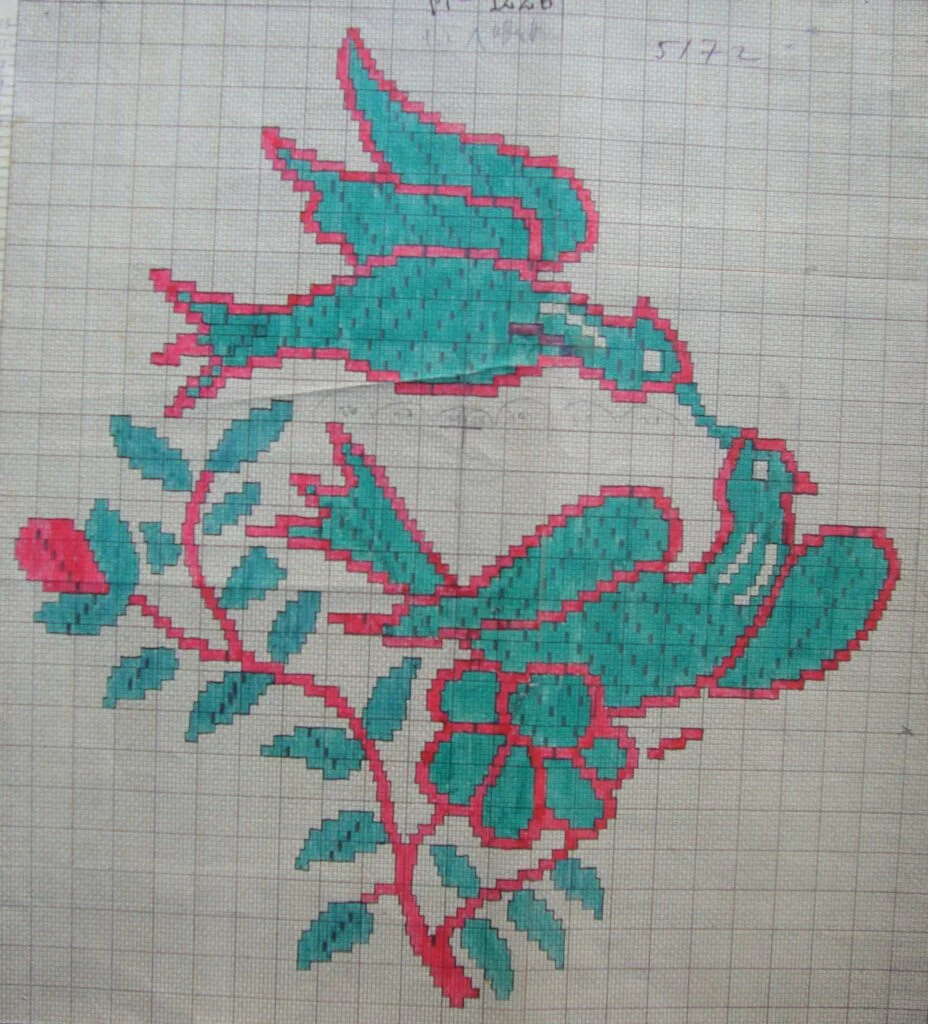

The modernization of weaving looms led to the development and acquisition of new knowledge and skills. In Damascus, the first pattern transposers were two Armenian brothers: Dikran and Yervant Stepanian, the latter is still alive in Damascus. After having fled from the massacres in Diyarbakır in southern Turkey and finding refuge in Cyprus, they went to Beirut, where they learned the craft of pattern transposing from their uncle Hagob, an employee of the Lyonese merchants. In this process, desired patterns are transposed to a drawing with millimetre precision in order to produce the punched cards for Jacquard looms on this basis. The two brothers reached Damascus in 1937 and their skills were appreciated by the city’s weavers.

The Mezannar factory was among the first of their clients. In 1947 President Shukri al-Quwatli commissioned the Mezannar brothers to produce an original design for the wedding of the then Princess Elizabeth of Great Britain (later queen) to Philip Mountbatten. The brothers designed the “Inseparable Ones” (ʿashiq wa maʿshuq). The Queen was offered 200m of white silk brocade, interwoven with gold. To this day this style of brocade is called “Elizabeth” when it is sold in the souks.

During the Second World War, the Mezannar looms were mobilized to weave silk cloth for British parachutes. In 1942 demand for silk cloth was so great that 410 tonnes of additional cocoon had to be imported for spinning in Syria and Lebanon.

The Mezannar factory is part of a long history of silk in Syria. In the 20th century it underwent many changes in connection with colonization, globalization, mechanization, etc. While silk and its weavers were Syrian, the tools ceased to be so. Nevertheless, the craftsmen were able to imprint their culture onto the fabrics.

The Mezannar family has preserved two catalogues from the Victoria & Albert Museum in London: A Brief Guide to the Persian Woven Fabrics (1922) and A Brief Guide to the Turkish Fabrics (1923). These catalogues contained photographs of designs of ‘oriental’ fabrics – originally woven in Central Asia, Persia, the Ottoman Empire, and Andalusia – from European collections or textile museums. In Damascus, Antoun Mezannar a Syrian weaver and international businessman, took inspiration from these collections of ‘oriental’ silk. He selected the sketches that he thought were best suited to express his culture, and had them produced by an entire chain of craftsmen.

| Gallery of the Mezannar factory in Damascus

In the 1960s, the Arab Socialist Baʿath Party nationalized Syrian private schools and companies. Throughout the country the large families that were connected to the textile industry found themselves undermined. At the beginning of the 2000s the Mezannar family was told that it was to be commandeered by the State. In July 2010, after an agonizing wait spent in stifling and bitter anger, the Mezannars watched-on helplessly as big parts the factory were destroyed. Nevertheless, some looms could be saved, so that Tony Mezannar continues the family tradition of silk brocade weaving to this day.

Featured image: Preparation of spools in the textile factory of the Mezannar family | Florence Ollivry (CC-BY-NC-SA)

Published by Florence Ollivry: In Syria, Florence Ollivry was interested in the history of food and sericulture. She holds a doctorate in religious sciences (University of Montreal; EPHE-PSL) and her research currently focuses on the mystical dimension of Islam.

Ok nice

Ok nice