by Elisabeth Korinth

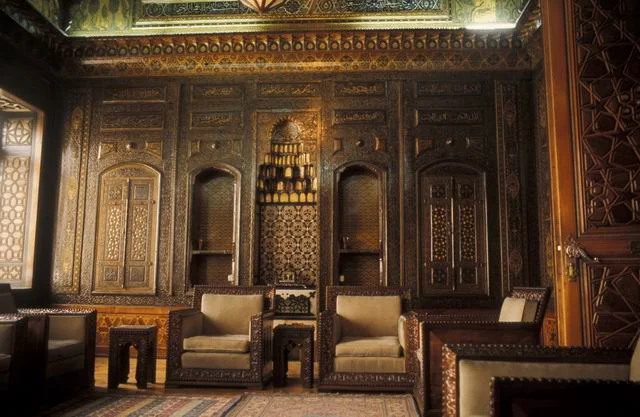

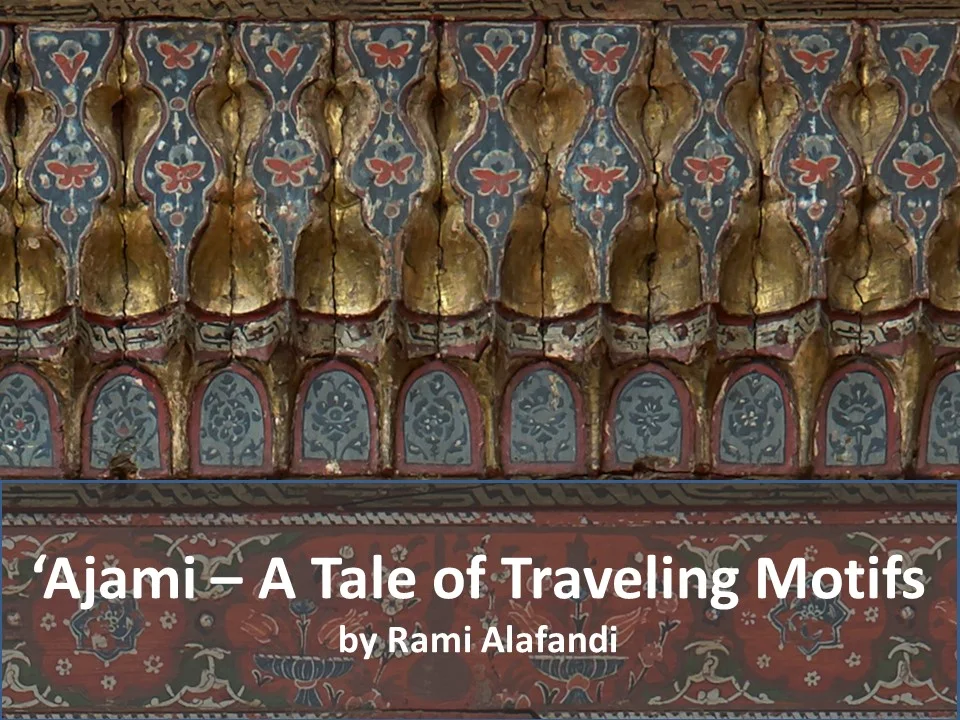

Rooms decorated with ‘Ajami originally consisted of series of framed wooden panels that cover the walls and ceiling, integrating doors, windows and cabinets into their design. Usually poplar, cedar, cypress or walnut wood were used for the panels. Some types of wood also vary within individual rooms: in Damascus, for example, ceiling panels and frames were often made of poplar, while doors and shutters were made of harder wood, such as walnut wood. In Aleppo, cedar and walnut was most often used. The individual panels usually left some gaps in between, which were often filled with organic material.

| Preparation of the wood

The panels itself were held together with an adhesive of vegetable fibers, animal glue or simply nails. Sometimes the panels were covered by cloth in order to hide the joins or cover nails. In the al-‘Azm palace in Hama paper was used as a base to hide nails and transitions. Before applying the ornaments, the wooden panels were elaborately processed with different tools and materials, and primed. The wood surface was usually individually prepared depending on the different requirements of the subsequent decorations and paintings. Commonly, a mixture of unburnt gypsum and animal glue was used as a primer (gesso). Sometimes primers were created in light blue, orange or yellow colour containing indigo, minium (red lead) or orpiment. In some cases, as in the Aleppo Room in Berlin, the tin foil was directly applied to few panels using a sticky resin layer, whereas in Bayt al-Hawraniya in Damascus the ‘Ajami decoration had been applied to some wood panels before the tin decoration. Today, however, the wooden panels are often replaced by MDF (fibreboard) as the material is cheaper and easier to use.

| Predrawing: Patterns of ‘Ajami decoration

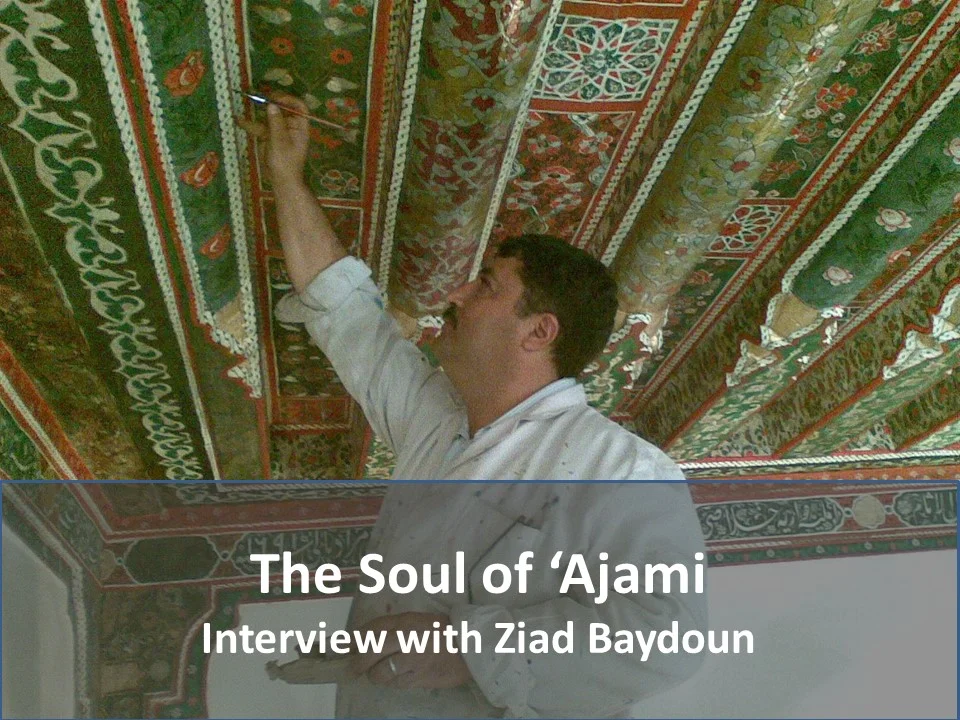

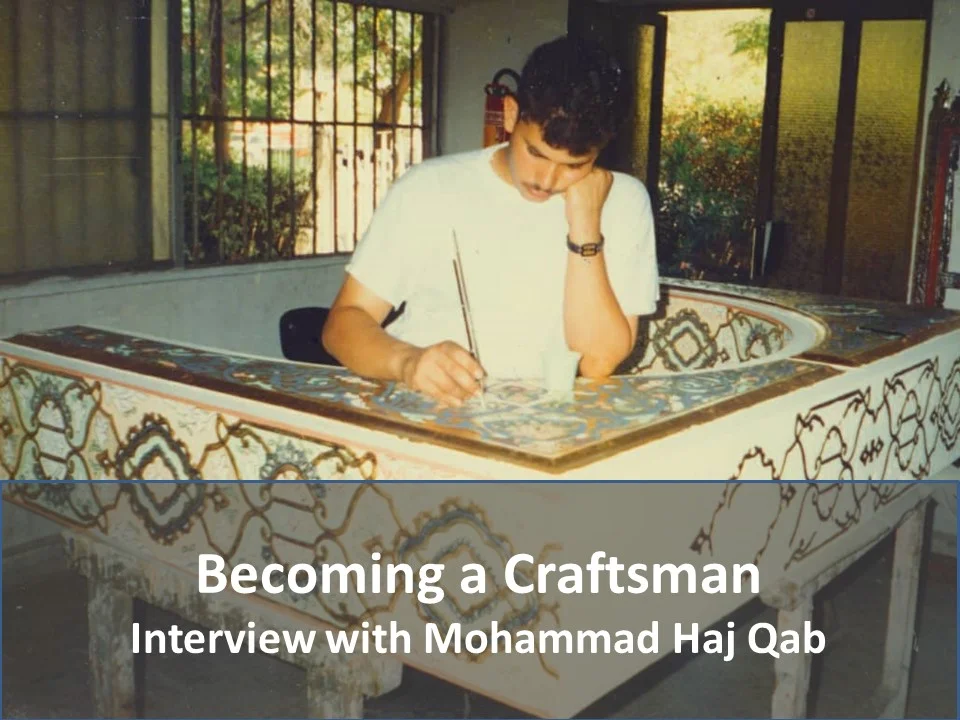

For the decoration and painting of the wooden panels, stencils were used for underdrawing. Therefore a paper sheet punched with lined holes was laid over the wooden surface. Then a small textile bag filled with charcoal powder was pounced over the stencil. This way, the outlines of the ‘Ajami transferred to the primed ground. Individual ornaments that did not follow the regular pattern were drawn free hand.

| The relief application

Following the sketch, the ‘Ajami decoration was applied as raised motifs. Here, the correct composition of the paste of the relief decoration (Nabati) played a crucial role. Only with the right amount of water, glue and plaster the viscous mixture of unbaked gypsum and animal glue would lead to the desired relief. Incorrect composition of the different elements caused the paste to sink, leaving a porous layer. Today, artisans mostly use a mixture of acrylic binders, chalk, gypsum and zinc white.

| Najeene ‘Ajami or Nabati

Especially the composition of the relief paste (called Najeene Ajami or Nabati in Arabic) is often a strictly guarded secret. The master himself usually mixes the paste. Many myths and rumors surround the making of the relief paste – add a little sugar…add a little tea. Some believe the secret lies in mixing the colours with bare hands, arguing that the human skin contains enzymes that accelerate chemical reactions in the paint and therefore make an important contribution to its quality – a hypothesis that has never been confirmed by scientific research, but adds to the mysterious aura of the craft.

| Application of metal foil

After the relief layers have dried, metal foil (mostly gold leaf or tin foil) was applied to certain areas or on the entire surface with the help of binders. From the 18th century onwards, copper alloy leaf was increasingly used. The choice of binder was also dependent on the type of material that was applied to the underlying paste. For example, the underlying raised motifs were moistened for the application of gold leaves. Today, the foil is often replaced by bronze paint.

| Colouring of ornaments

In the next step, various areas of the metal layer were polished and painted with a tinted glaze. One started with the larger surfaces and then continued with the smaller ornaments. The glaze used to be made of colored natural resin. This not only improved the appearance, but in some cases also protects particular surfaces like brass from corrosion. Non-glazed areas are today clearly recognizable by a change in the color of the metal. Today, modern colours are used to paint the surface.

| Painting between the relief

Areas that were not highlighted as relief were richly painted. The most popular motifs were recurring floral and geometric shapes as well as flower bouquets and fruit bowls. The pigments used were lead white, orpiment, vermillion, lapis lazuli, verdigris and carbon black as well as organic dyes as for example kermes, indigo, cochineal, and aloe. However, how the binders and colours were made is not documented. An important part of the knowledge of the 17th and 18th century painting is thus lost. Only through scientific analysis, the components of the colours could later be identified. The rich ornaments are then outlined in black or other colours and individual flowers are shaded. The outlines and the shadowing of the various ornaments are important to illustrate the shape and condition of a motif´s surface. As a result the painting not only reflects a picture but adds a spatial dimension to it.

| Final Touch

The rich ornaments are then outlined in black or other colours and individual flowers are shaded. The outlines and the shadowing of the various ornaments are important to illustrate the shape and condition of a motif´s surface. As a result the painting not only reflects a picture but adds a spatial dimension to it.

| ‘Ajami rooms

An ‘Ajami artwork can be considered a living organism. The wood as well as the colours continuously react to their environment. This knowledge and the harmonization of the individual components with nature and its laws were essential for the quality of the work especially in historic times. The correct composition of the colour, for example, depends on the season and the humidity of the place where it is made. Wood, as a living material, cracks and expands depending on the weather. New material such as MDF (fibreboard) has helped to make the practise of the craft easier as it has a soft surface. However, much of the knowledge and original aspects of practising this craft fell into oblivion over the centuries.

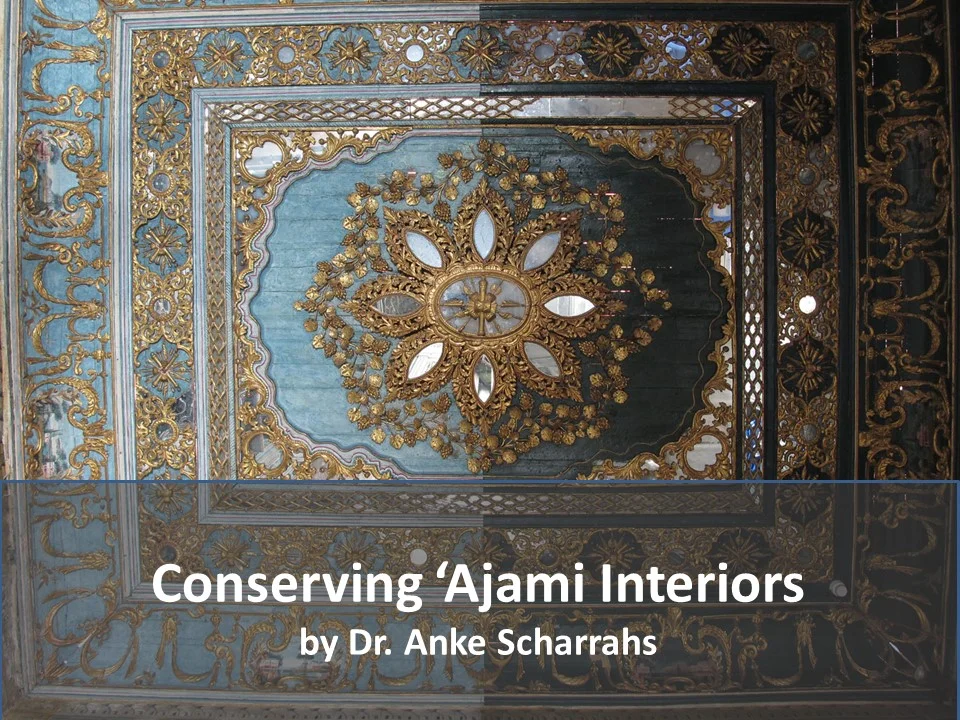

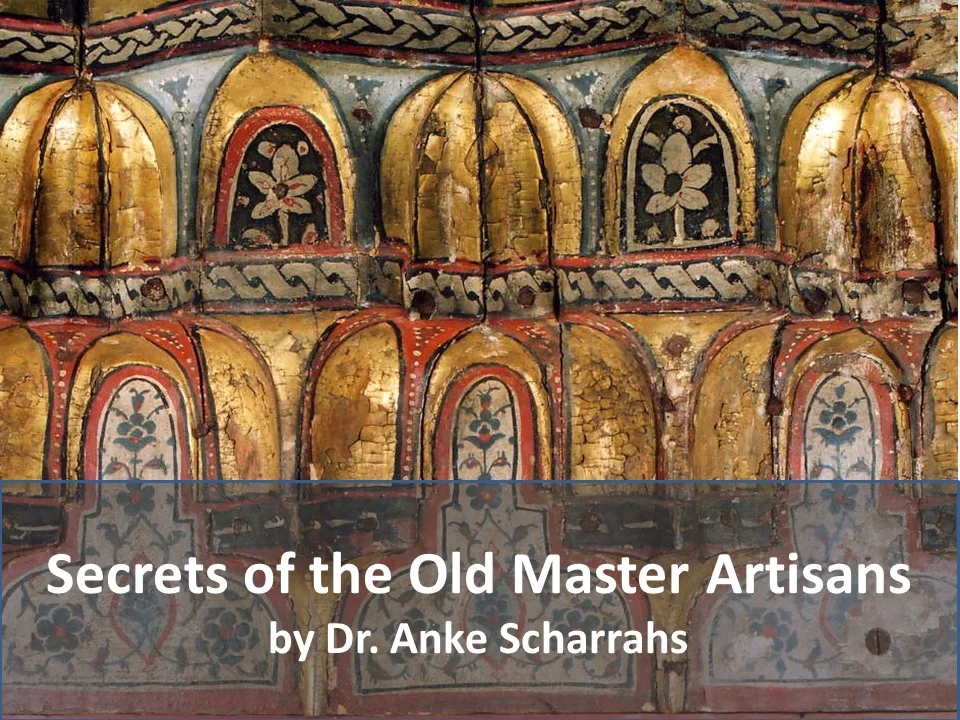

Raising awareness about the importance of safeguarding traditional handcrafts not only includes fostering the practise of a craft itself but further requires the involvement of other disciplines related to the safeguarding of the historical material heritage such as the field of conservation. Furthermore, there is a need of comprehensive research that is able to unveil historical trails of a craft in order to better understand their development over time and their interpretation in present days. Anke Scharrahs has dedicated her professional career to the conservation and research of polychrome decorated wooden interior work. It is due to her comprehensive research, amongst others, that the various layers and work stages of the production of the polychrome decorated panels in historical times can be understood.

Amazing art, I like to go back one day to Syria and join the course with her. Need her contact details.