by Elisabeth Korinth

Ziad Baydoun is an ‘Ajami craftsman who is both practising and researching the art of ‘Ajami. Together with his father he is running a workshop in Malaysia. In our interview, the artist shares his personal story with this craft, why it is worth safeguarding and how he ended up working in Malaysia.

Ziad, what makes ‘Ajami work so special for you? What do you find unique about it?

Every drawing has its own spirit as each person has its own style to draw. The way someone is drawing the motifs in ‘Ajami work always differs to other painters. A yasmine flower is still a yasmine flower, but the way it is realized by the artisan in his painting is unique. It is like a personal fingerprint. Have you seen the movie The Da Vinci Code? I like to compare ‘Ajami to the Da Vinci Code. When you look at the painting and the relief, you will know who the drawer was and who the owner. In old palaces, you can easily distinguish which room is for women and which room for men or guests by means of the Ajami decoration and calligraphy. In women´s areas you may find poems about women. You may find kind of codes in their calligraphy refering to the owner of the house, praising his hospitality and generosity. I like to include hidden messages in my pictures as well. On the one hand, they help me to recognize the image by integrating my signature. On the other hand, the work becomes something unique this way. I use the names of the inhabitants, their zodiac signs and dates of birth. Often I inquire about the personal taste of my clients – their favourite colour or the favourite flowers of their children, for example. People always look at Islam as a religion that is fighting and killing. For me as a Muslim person, I wanted to learn this craft to show people that Islam is not just fighting. Islam is also art and beauty.

How did you get interested in working with ‘Ajami?

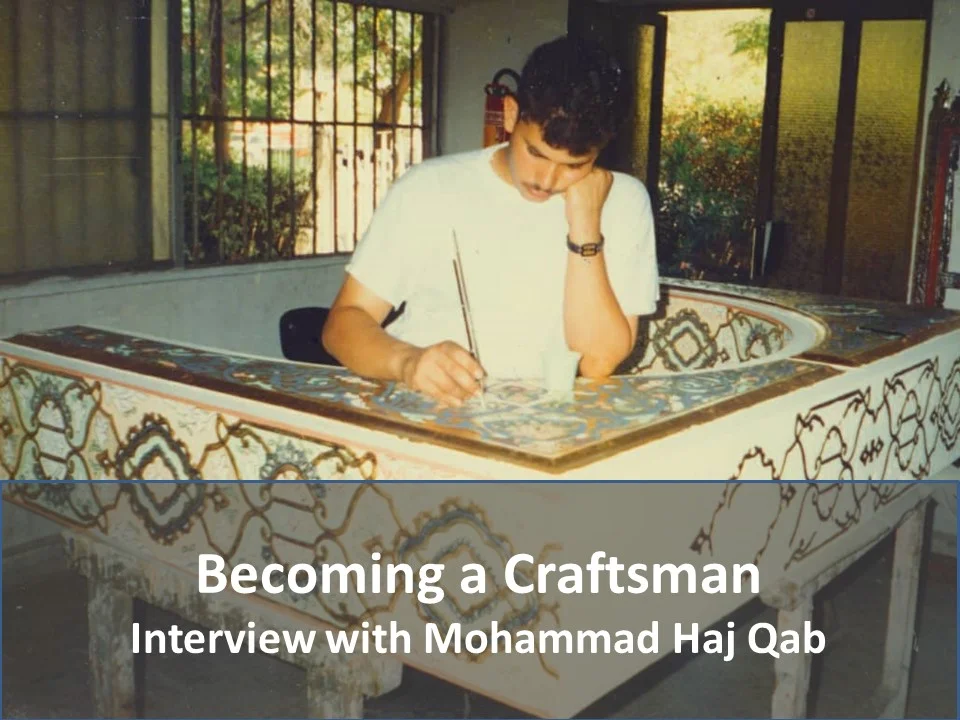

Abdelraouf Baydoun working with the craft of ‘Ajami in Qasr al-ʿAzm (© Ziad Baydoun from Baydoun Creation (CC-BY-NC-ND)

To be honest, when I was young, I did not appreciate the art of ‘Ajami at all. I felt like my father is wasting his time and was sure that he will get tired one day and just leave it. So, when I started studying, I focused on modern art and wanted to open my own workshop. Somehow, I did not want to follow my father´s identity. I really wanted to build up my own identity. And I was succesfull. I had a good income and was working with 3D. But I could see it in people´s eyes that they looked differently at my work than when they looked at my father´s art. The message of his work always seemed to carry something for the future. People did neither forget his name nor his work. There was something that fundamentally distinguished his work from mine. It is a kind of jewelry.

While I was in University, my father would only give me money, when I worked for him. One of his projects was in Hama and went over 5 years. So everytime I needed money, I helped him in his project. When I graduated, it was still running and I continued for a while. Throughout the work with him my perception on ‘Ajami slowly changed. Everytime we finished a work, we were stunned and wondered: Was it really us that made this? I started loving this art and loved it even more when I started researching about it. In the following years, I realized that this kind of work is worldwide accepted and that there are many rooms all over the world cladded with ‘Ajami work.

In your research you have identified 15 different stages when working with ‘Ajami. Which stages do you find particularly difficult? Was it difficult to learn all the details?

The development of the overall design for the painting and its application on the wood. This is really difficult. Even I, with a background in interior design, find it difficult and sometimes I just take parts of the designs of my father and repeat them. One can learn everything, but for the design part you need to be a creative person. It needs to be someone who can just take the paper and draw – who knows how to compose the colours and experiment with them. It is similar to music, if you don’t know the notes you will never be very good. You need to know it note by note. Another important part of the ‘Ajami work is the mixing of colours and the Nabati (relief paste). We usually apply the Nabati material to the whole panel and then wait for two to three days depending on the area where you have your workshop. In Germany it is different to Syria or Malaysia. Seasons control the time as well as the amount of glew I have to use. These conditions need to be included in your calculation.

Pre-drawn pattern of a contemporary ‘Ajami decoration (© Ziad Baydoun from Baydoun Creation, CC-BY-NC-ND)

Some workshops hold this as a secret. In my opinion it is a mistake to hide this knowledge. This kind of art will be dying if we hold on keeping things secret. Some people are concerned that someone else might do their work. Why would you worry about that? If you have the creativity you do not have to be worried. So thank God, I was able to get all information. I learnt it from my father and even wrote it down. It makes me so happy. There is something right about it and the craft shouldn´t be dying.

You are currently leading a workshop in Kuala Lumpur. When did you decide to go to Malaysia and how it is to work with a traditional Syrian handcraft in a different cultural context?

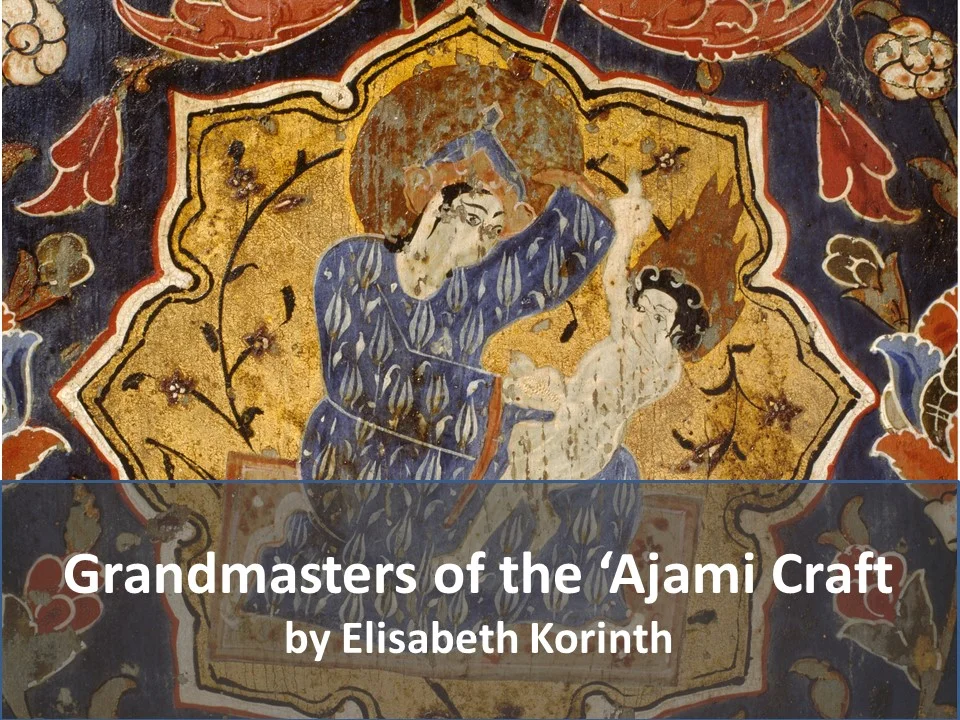

Modern painted panel with ‘Ajami decoration in Ziad Baydoun´s workshop in Malaysia (© Ziad Baydoun from Baydoun Creation, CC-BY-NC-ND)

My father was working with ‘Ajami for 45 years in Syria. When the war broke out in 2011, tenders for work went down and I moved to Malaysia. From that point onwards people in Syria just wanted to survive and stopped thinking about restoration work. After a while, I started recognizing that my father became depressed, not only because of the situation in Syria. But also because he couldn´t do anything. There was no work. I kept on asking him, if he would like to come to Malaysia to open a workshop with me here, because I did not want my father to feel that he is useless. I thought that Malaysia is a Muslim country and they would therefore appreciate this kind of art. Finally, he came. But there were no projects. Nothing. I opened a workshop and did all the paper work. But we had no clients. The reality was different. ‘Ajami is a very specific Syrian heritage that is known in the Middle East. But Malaysian people think differently. Their heritage is unique in its own way.

But despite the difficulties, my father would get up every morning and go to work from 8 in the morning until 9 in the evening. He just sat, drew and enjoyed. It felt like he was really exploring and expressing his feelings into his work. If you go back to his paintings, you will recognize when he was angry and when he was feeling good. If his painting is very smooth, it means he was happy. You can sit 8 to 9 hours working on ‘Ajami without getting bored. When you express your feelings into the drawing and then you can see the result and see people´s reaction to it – you feel glory in your heart.

Visit Ziad Bayoun´s website to find out more about his workshop