by Manfred Strauß

Most Syrians know the Syrian State Railway (CFS) only by name. Those who want to travel prefer to take the bus to get to their destination faster. Nevertheless, the Syrian railway has well-equipped, comfortable passenger and sleeping cars. Passenger and goods trains rolled across the country on an extensive rail network (until 2011/12). In order for the trains to run smoothly throughout, the network must be regularly maintained. In the late 1970s, a certain backlog of modernisation had accumulated and Syria asked the then GDR for technical support. In 1980, a state treaty was concluded between Syria’s state railway and the GDR Ministry of Foreign Trade, covering signal boxes, rail maintenance and general technical modernisation.

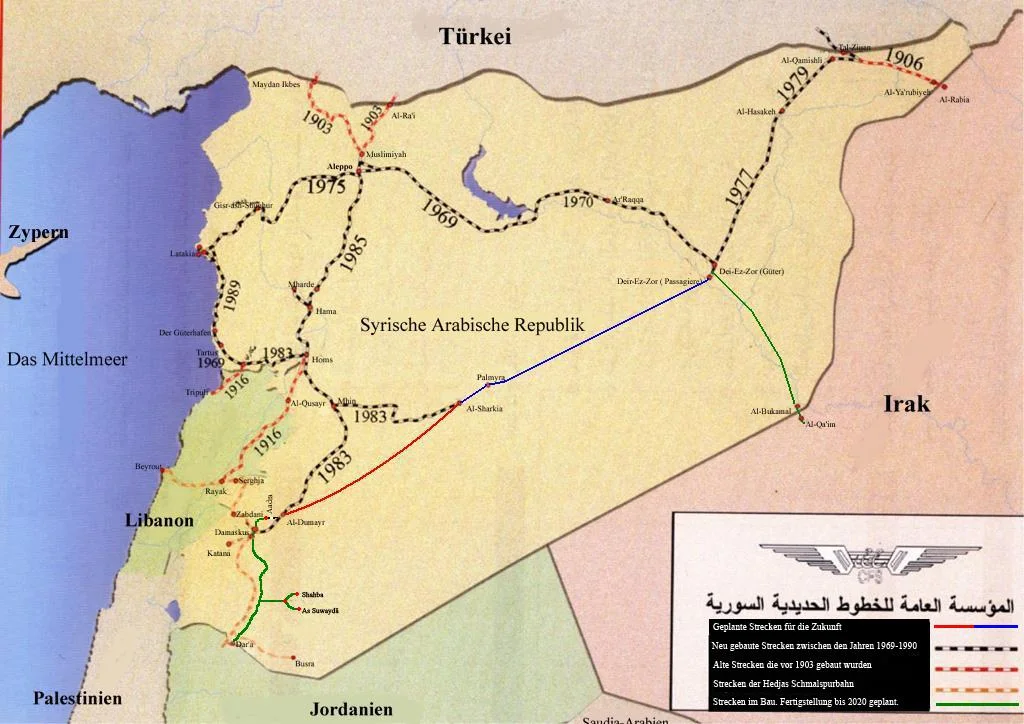

Railway line development in Syria

Only short sections of historic Baghdad Railway, built from 1903 onwards, are in Syria: in the west a branch to Aleppo, completed in 1912, and in the east a short section between Qamishly on the Turkish border and Al-Ya’rubiyya on the Iraqi border.

Already at the end of the 19th century, two railway lines Damascus – Mzayrib and Damascus – Beirut were built as narrow-gauge railways. Probably to ensure the connection to these existing lines, the Ottoman Empire began building the Hijaz Railway in 1900 with a narrow gauge to bring pilgrims from Damascus to the holy sites. Its rail network also included a branch to the Mediterranean port of Haifa, the connection to the existing railway line to Hama and Beirut and later the Dar’a – Bosra branch.

The different gauges made the development of a Syrian railway network enormously difficult. The newly founded Syrian state railway “Chemins de Fer Syriens” (CFS) began to build a standard-width rail network for the entire country. The most important connections built from 1969 onwards were: from Aleppo to the port of Lattakia and eastwards to Raqqa, with continuation to Dayr az-Zawr and Qamishli, where the connection with the rails of the Baghdad Railway was achieved. The Damascus – Aleppo line, built in 1983-85, was the busiest section until 2011/12. Before July 2012, there were also international rail connections to Turkey and Jordan.

Even of greater economic importance than passenger transport is the freight transport for Syria.

From 1980 to 1984 I worked as a German expert within the cooperation for modernizing the Syrian rail network. Together with my family we lived in Homs. The railway facilities of Homs are an important hub of the north-south as well as east-west connection routes, the latter especially concerning freight traffic between the interior of the country as well as the ports of Tartus and Latakia. Here, I would like to explain the work I carried out on behalf of my company, the Werk für Signal- und Sicherungstechnik (WSSB in East Berlin).

We were responsible for 48 buildings for signaling equipment for automatic railway operation, 25 fully automatic barrier systems, the laying of signal and telecommunication cables, as well as an automatic telephone exchange in the Homs II railway control centre. The construction staff we worked with was based in Homs, where all activities for the administration, coordination and hiring of manpower, etc. were concentrated. Our material and distribution depot, with the vehicle fleet, was located near the signal box in the village of Baba Amr, with a corresponding siding to the Homs freight station.

I was employed as the warehouse and vehicle fleet manager and at the same time was responsible for both the workshop and the local workforce such as painters, drivers and warehouse workers.

All preparatory work, such as painting signals, preloading batteries or similar, was carried out at the camp premises. Since the existing wayside signals were of Russian design, we had to import their spare parts and pre-assemble them on the camp forecourt. All concrete foundations for signals and barrier drives were manufactured in Baba Amr and delivered to the site, thus ensuring the contractually agreed share of local added value.

We lived in rented public apartments or with private landlords. The furnishing for the flats was provided by WSSB, so that every colleague had the same furniture. Transported in 20-foot containers, they contained everything from small spoons to a wall unit that we might need on site.

Our vehicle fleet comprised 6 cars, about 30 jeeps, a minibus, a measuring van for cable laying, a truck-mounted slewing crane, a truck, a low loader and a track motor car.

The lightning strike

We did have a siding, but it was hardly ever used because all materials were brought to us via the ports of Tartus and Latakia and then transported by truck.

While normal everyday life went on in an orderly fashion, I do remember an exceptionally dangerous situation when a shipment of cable drums from the port of Tartus arrived at the camp in Homs on the afternoon of 24th December 1981. Normally it was agreed that deliveries would be announced one or two days in advance. This time it was different.

The low-loading truck with 24 drums had to be unloaded immediately. I looked for a volunteer who needed to get the cable drums ready for lifting. Somebody else needed to operate the truck-mounted slewing crane, and that was me.

Suddenly a thunderstorm rolled in. We had just unloaded three drums, and the fourth was hanging on the hook – then a lightning bolt struck the tip of the crane. The shock was huge, but no one was hurt. After a short break, we continued unloading the truck and were able to celebrate Christmas that evening, at home, safe and sound.

Everyday life on the railways

Contractually, seven sections of track were agreed: Section I Homs – Mhin, Section II Mhin – Al Sharkia, Section III Homs – Tall Kalakh, Section IV Tall Kalakh – Tartus, Section V Homs – Hama, Section VI Hama – Aleppo, Section VII Mhin – Damascus.

We started laying the cables in the sections first. About 650 km of track cables were laid in various subsoils, partly through rocky or sandy subsoil or through streams. The cables had to be laid to ensure communication with the individual signal boxes. This work, as well as the cabling of a station and the barrier systems, was done by local subcontractors.

In the next step we completed the outdoor facilities. These included the installation of siding boxes, mounting of point machines, laying of foundations, installation of signals as well as completion of the fully automatic barrier systems.

Syria’s rail network is still largely single-track, which means that oncoming trains can only ever pass each other at stations or at passing points. Coordination between signal boxes and train drivers is therefore enormously important. The work with the work train was particularly dependent on timely telephone arrangements. Nevertheless, once, a dispatcher at Homs station sent a freight train off in the direction of Shanshar and we were simultaneously on our way from Shanshar to Homs with our work train, i.e., with crane and signals. Only the quick actions of both train drivers prevented a collision! They had totally forgotten to make a phone call!

Occasionally, the locomotive drivers created difficulties for us, as they were not used to waiting at a red signal and thus often caused mechanical damage to the track switch.

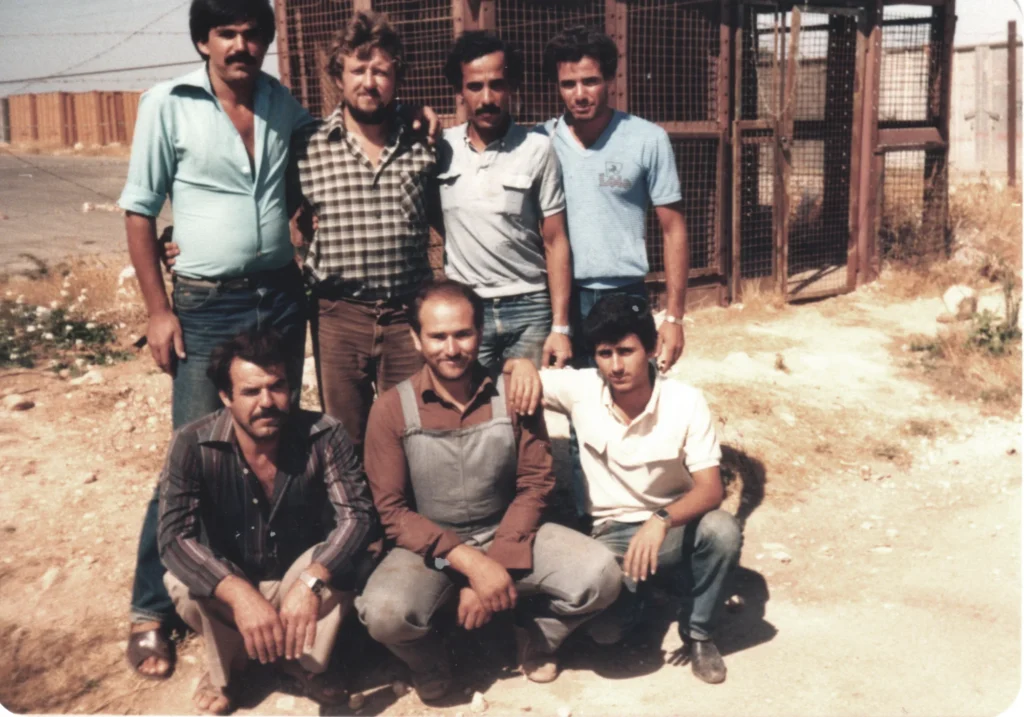

After the completion of each section, a small celebration was held with all the Germans and Syrians involved, because those who work together can also celebrate together. The cooperation with the Syrian colleagues was extremely positive and very friendly. A few of them had received electrical engineering training, which was obviously an advantage, as they were able to work independently in some cases.

My activities included guiding Syrian colleagues in our workshop and during assembly. The Syrians’ thirst for knowledge was enormous; there were detailed discussions on every question, which helped them to consolidate their knowledge and further qualify themselves to carry out work independently. We learned from each other, the Syrian employees acquired knowledge about German railway techniques and used German words, I learned more about the customs, culture and language of my Syrian colleagues.

We also had very good contacts with workshops in the Homs industrial area. Among other things, our vehicles were repaired here when needed.

One day, for example, I had to take my company car to the Peugeot workshop to have the tie rod ends replaced. Abdul, the workshop boss, said we had to do a test drive and so we left the industrial area in the direction of Hama. Whilst doing about 100 kilometres per hour he loosened the steering wheel, lifted it off and adjusted it again! Anxious seconds passed, but all went well.

Besides working we had the opportunity of travelling around the country, which we took advantage of. Since the port city of Tartus was not far from Homs, we could enjoy a swim in the Mediterranean Sea on many a Friday, this being our day off from work.

In August 1984 I finished my foreign assignment and went back to Germany with my wife and our daughter, who was 5 years old by then. It was a very difficult farewell, as we had spent four happy years in Syria and had made many good friends.

Coming back to Syria

In 2000, we set out with friends and former work colleagues on a private journey from Aleppo through Idlib, Latakia, Tartus, Hama, Homs, Palmyra, Maalula, Damascus and Bosra. Of course, we made a longer stop at our old workplace in Homs.

Here we were most warmly greeted and welcomed with the familiar ritual of drinking tea together.

Farwas, our former driver, was now the warehouse manager and handled all the materials.

With the help of old photos, we were able to find our former landlords. Many new buildings had been erected and Homs had changed for the better. The landlord’s family were overjoyed. They wanted to take us straight to Tartus to their bungalow, but unfortunately, we had to decline, because that evening we were going on to Marmarita.

Featured image: Physical strength was also needed to run a track motor car onto a wagon with the help of a crane truck | Manfred Strauß (CC-BY-NC-ND)

Published by Manfred Strauß: Manfred Strauß lived in Homs with his family from 1980 to 1984 to contribute to the modernisation of the Syrian railway system. These four years in Syria had a positive influence on his view of the world.