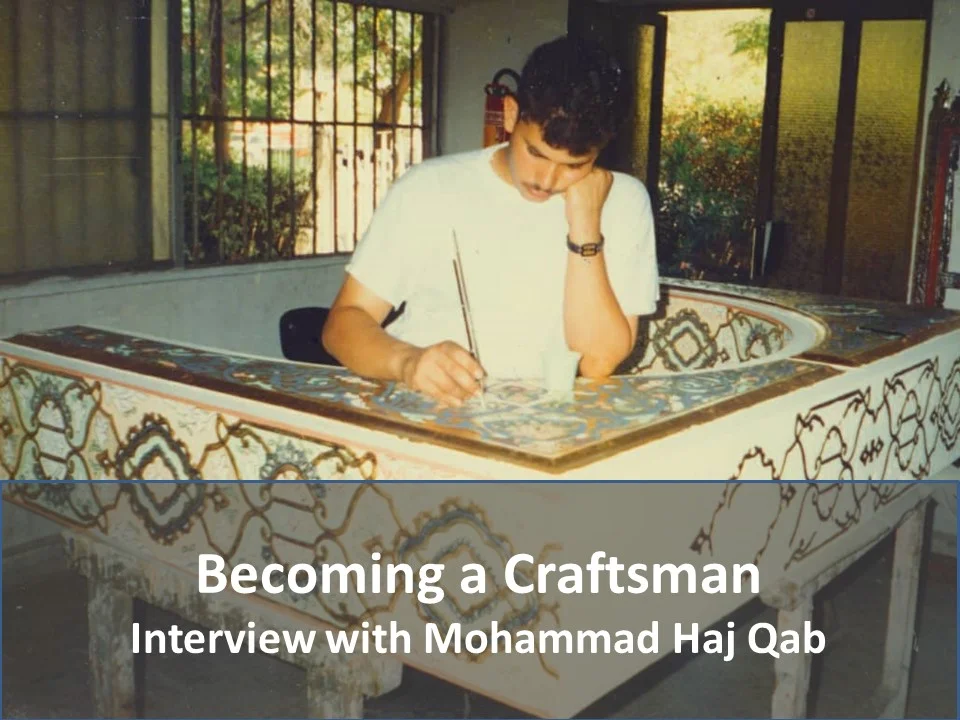

Interview by Interactive Heritage Map team

Aliya Alnuaimi is an artist who lives in Damascus working with the sophisticated craft of ‘Ajami. In her private studio, she teaches the craft and conducts art exhibitions. Being one of the few known women working with this craft, Aliya shared her experience in this field giving a personal female perspective on the issues of innovation when working with a traditional craft.

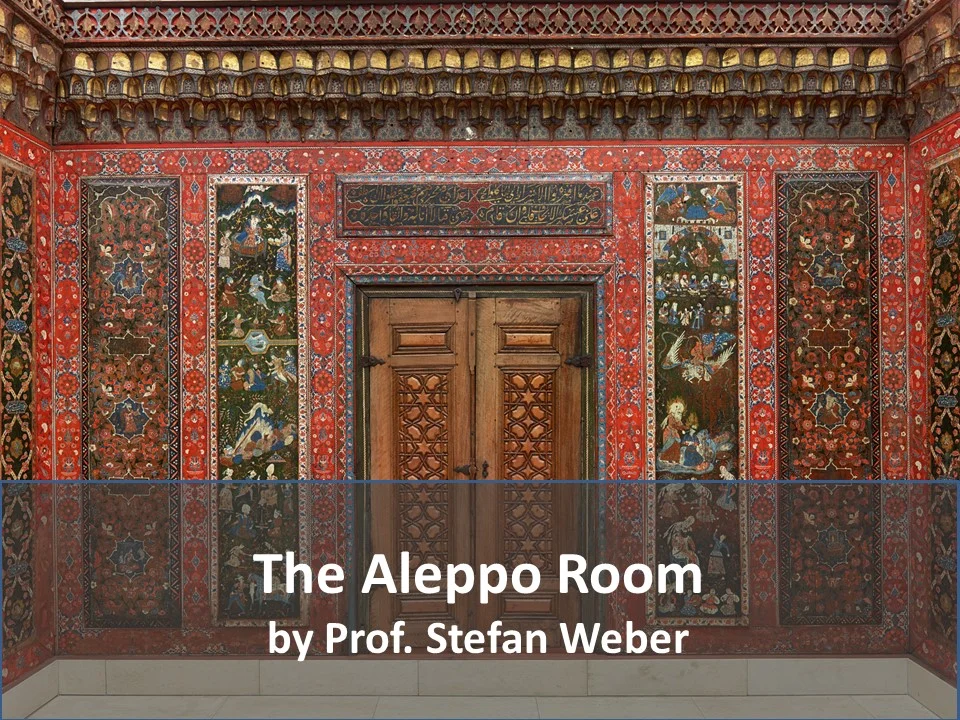

Aliya Alnuami is experimenting with new ways of painting and decorating ‘Ajami work | Aliya Alnuami (CC-BY-NC-ND)

Aliya, you are an artist with a passion for the traditional craft of ‘Ajami or, as you call it, Damascene paint. How did you learn the craft?

Since my childhood, I have always been interested in the art and decoration of traditional old houses in Damascus. So I frequently visited a workshop for Damascene paint (‘Ajami) near my house when I was younger and started observing and trying to paint on my own for about a year. The workshop owner was not willing to teach me this craft. Later, when I entered the Faculty of Fine Arts, I found one course that explained material characteristics and painting techniques in general, also referring to the ‘Ajami craft. However, the exact quantities of the ingredients used where not taught to us. In consequence, I experimented until I got a similar paste in texture and characteristics of that used in the workshop I had visited. Since then I work and develop my own paste and was able to master the different stages of the craft with my own material. Nowadays, most of this knowledge is publically available.

Can anyone learn it? What is the required practical knowledge to learn the craft?

Anyone can learn the craft, provided that they are willing to learn and have a steady hand in drawing. One can learn at the workshops of the craft´s masters. Those who wish to practice the profession will go to a workshop owner and ask for employment. The apprentice then must train for a long time to learn the secrets of the craft in order to be able to work independently in the future. In 2015, I conducted a 3 month workshop in the Opera house with students ranging between 10- 60 years, coming from various academic backgrounds and with different motivations. Naturally, the results differed in their quality, but they are all considered a good first attempt. In the past two years, UNESCO has offered training courses in the handicraft market in Damascus, (in al-Takkiya). The theoretical training period is limited to less than one month. Participants can learn about the basic stages and their theoretical implementation. However, such a profession needs practice and those who want to master this craft must continue to work to develop their skills.

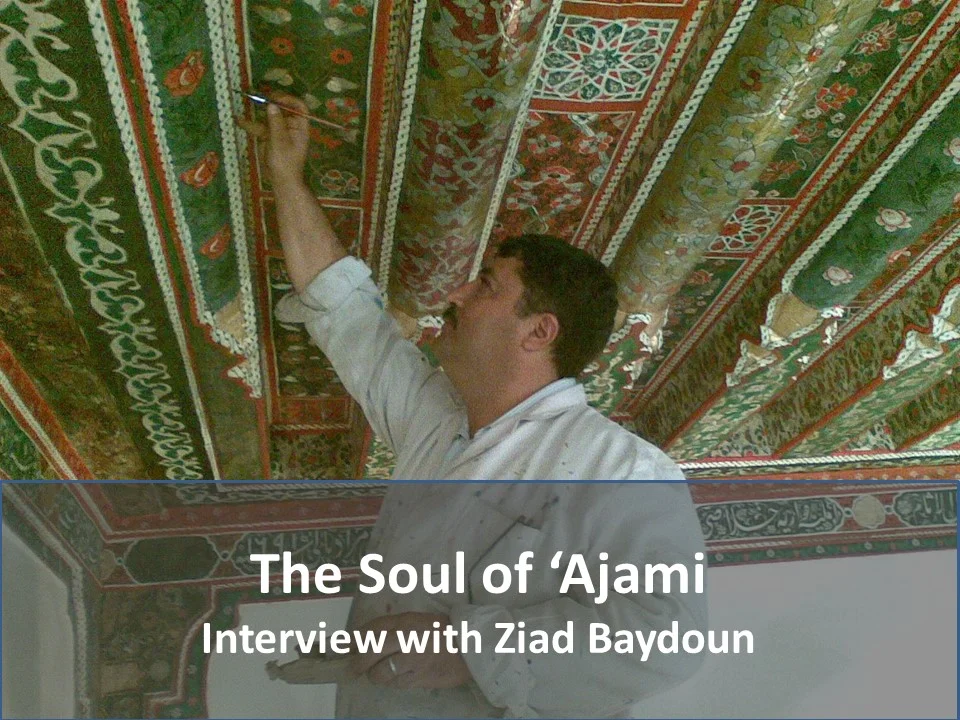

Aliya Alnuami is applying the relief paste on her ‘Ajami-work | Aliya Alnuami (CC-BY-NC-ND)

What is your experience as a woman working in a male dominated profession? Were there difficulties for you to learn it?

The biggest difficulty for me was finding someone who wants to teach me. If somebody wants to work, one can always go to any workshop and buy the material easily. But the workshop owner is not responsible for the rest. They consider this as a way to keep the craft’s secrets. I had some difficulties in the beginning and encountered some disapproval and apprehension to have this as my profession as a woman, until they saw my work and liked it. Even the craftsman, who issued the certificate for me, tested me for three days, although I had been practicing the profession for 17 years at that point. But he insisted on testing all the work stages and gave me the certificate reluctantly. One day I invited him to one of my exhibitions. He saw the paintings and asked me sceptically if I was the one who did this work.

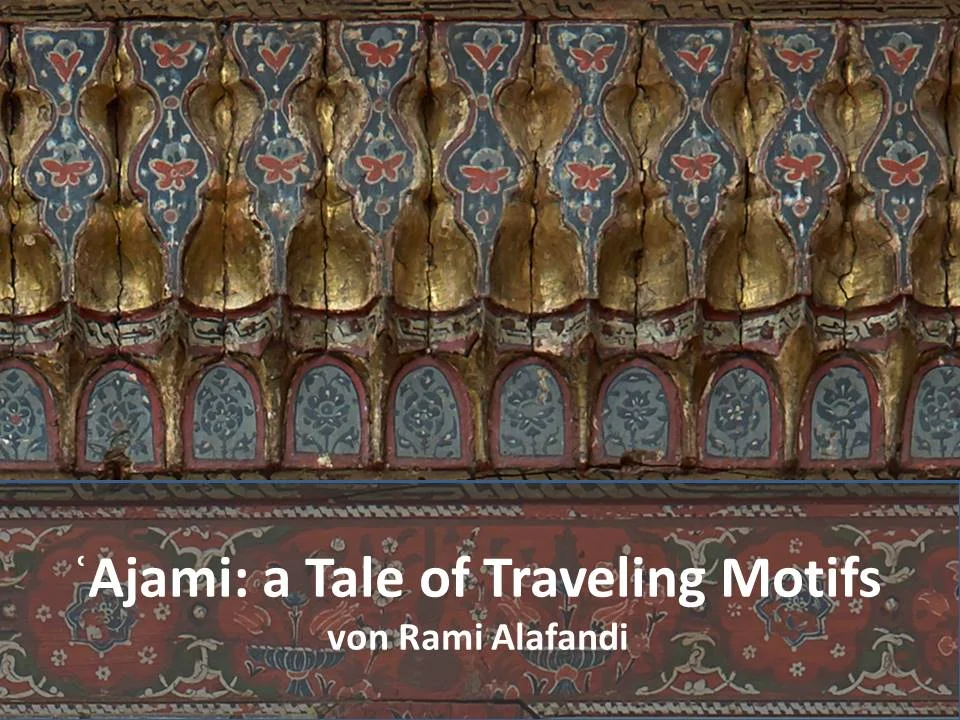

The variety and density of motifs, forms and colours are what make ‘Ajami such a rich decoration. How do you choose your overall design and its motifs? Are there any traditional patterns you follow or motifs you regularly use?

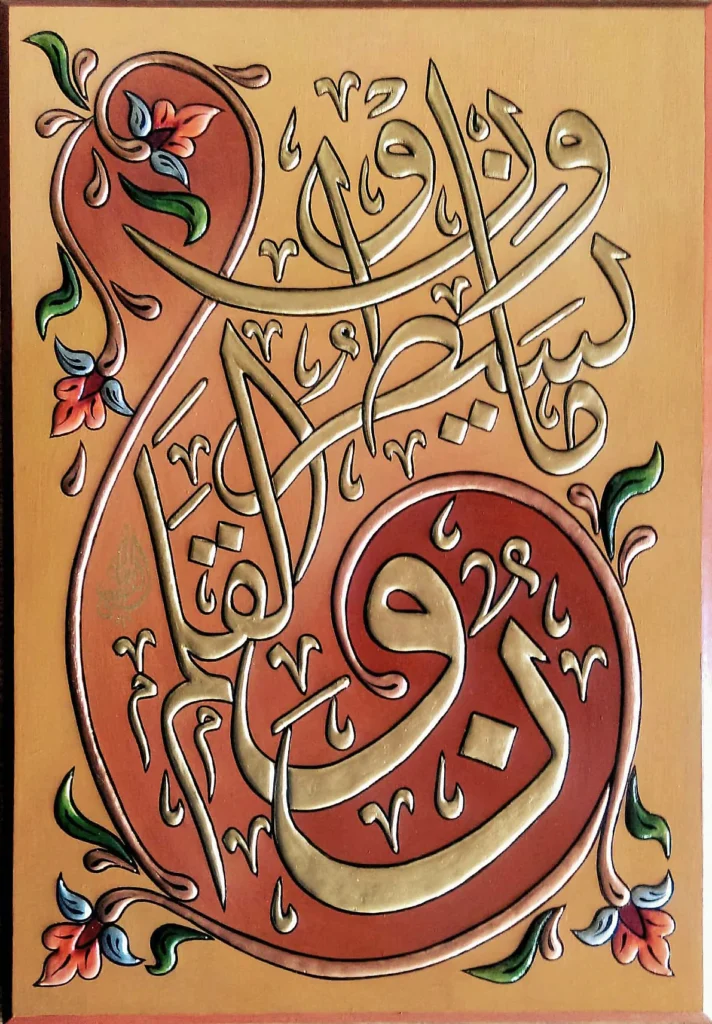

The patterns of decoration are varied and anyone can compose their own motif. It is possible to use a common pattern such as Fatimid ornamentation, geometric decoration, calligraphy, diamonds, octagons, and so on. Between these motifs one can integrate floral decorations. There are known decorative units like the Persian flower and the just mentioned Fatimid decoration which is based on an almond-like leaf. In addition, there is Arabic calligraphy, which is a vast open source including styles such as Diwani, al-Thuluth, Jali-el-thuluth, and Farisi. Well-trained craftsmen are able to create differents styles. In the end, each person leaves their own personal print. The master is the one who provides the basic design. He is the one who can picture the work and estimate the workload. He divides the space and imagines all the necessary steps in his mind. Then he conveys these ideas to the carpenter and to the craftsmen to implement them.

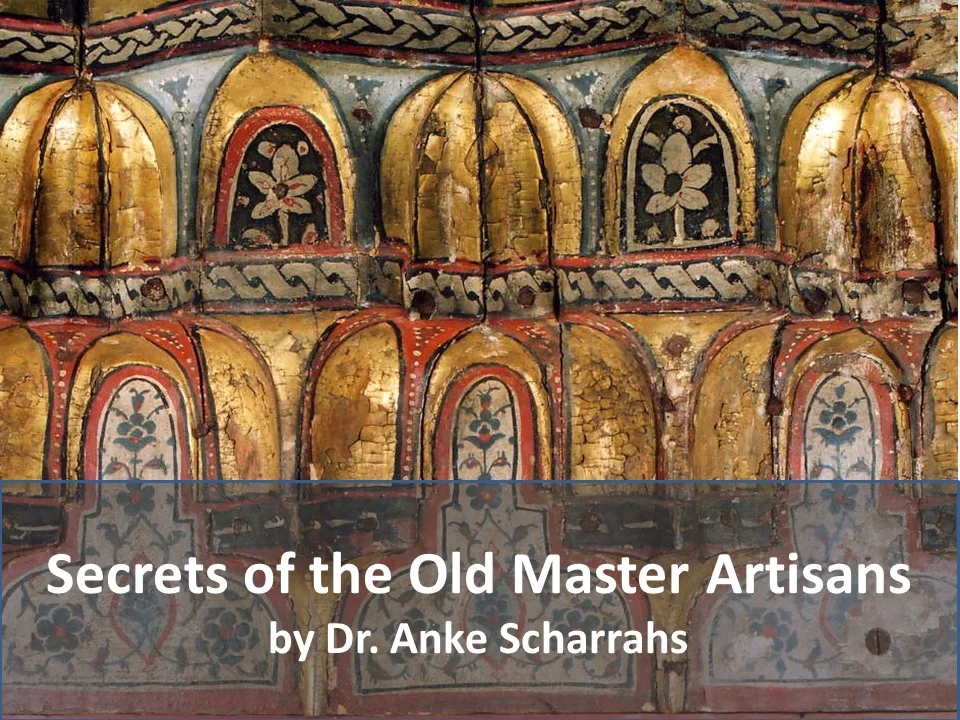

Your work presents a mixture of old traditional forms and the integration of new innovative ways of working with this craft. What is your opinion on transforming a traditional craft to something that is more modern?

Modern interpretations of the traditional craft of ‘Ajami in Aliya´s workshop | Aliya Alnuami (CC-BY-NC-ND)

I firmly believe that anything that cannot be developed has the potential to lose its luster or attractiveness. It is true that preserving the authenticity of heritage is necessary, but new generations need to be attracted to this subject in order for it to last. If they do not find it suitable to acquire and it doesn’t match their taste, it will get lost. The craft of ‘Ajami has always evolved in accordance to the available materials at any time. For example the colours have changed. Nowadays, craftsmen use acrylic colours. Some even use oil paints. There is a development of materials, but one main thing remained to be preserved by masters of the craft, and that is the basic paste mixture for the relief. So when I started changing it and used a different kind of glue, I faced criticism although the result was the same in my opinion. Previously, there was only red glue and there was no chemical or plant-based glue. This is why craftsmen used the traditional methods, using a water bath and creating the glue by hand. Also with regards to the wood types there have been changes: In the old times, they used natural wood which requires a different treatment because the natural wood cracks the drier it gets. In order to avoid this, there was a stage called “Tashiesh”, meaning covering the wood in lenin cloth and applying a layer of the same paint on it before decorating. However, now there are new material such as MDF as it has a soft surface and does not crack. I prefer development to ensure that the profession becomes easier to practice and more widespread.

You are also teaching ‘Ajami. What is your motivation to conduct workshop for others?

I like to share my knowledge and skills on this craft, especially since learning this profession was not available to me. I want to teach it for free and disseminate this knowledge to people because it deserves to be preserved. When such a thing becomes a public interest it gets more important than personal interest. The workshop owner likes to keep the secrets of his profession because of competition or maybe to prevent this craft to become something that is being massively produced. But this I consider selfish. Because the publication and dissemination of the knowledge is a means to preserve the heritage, especially lately as there have been many migrations, and many workshops had to be closed for various reasons. That is why we have a responsibility to keep this spirit alive and immortal for future generations.

Visit Aliya Alnuaimi on Facebook to get to know more about her work.