by Jabbar Abdullah

Traditional Ajami and Obaidi rugs are considered part of the long-standing folk traditions of the city of Raqqa, with links to the rural lifestyle, its agricultural traditions and livestock rearing from when the city was established up until 1990.

Maryam Ibrahim was born in 1956 in Kasra Sheikh Juma, a village near Raqqa. The village got its name from being the place where water refracts (Kasra) and notable resident Faisal Sheikh Juma, through the practice of villages and places being named after notable incidents and prominent early residents. Her forefathers and other relatives have lived there for over one hundred years. Kasra is around 10 km away from Raqqa, via the Raqqa-Aleppo Highway, which splits the village into two parts: to the north, there is agricultural land that ends along the Euphrates River. To the south are houses bordering a range of high limestone hills known for their mines, followed by wide expanses of land that are the pastures that support the life and lifestyle of the people of Raqqa and the surrounding villages.

Until 1980, the village was small and growing, with a population of several dozen residents who relied on agriculture and sheep farming. They would bake their bread from the wheat and barley they grew every year on the land they own on the banks of the Euphrates. Their livestock guaranteed them milk, cheese and ghee and from their wool they would weave the finest types of Ajami and Obaidi rugs, famous at that time and to this day. Maryam said, “At that time I was about 10 years old. That was when I started to learn how to make rugs at home from my mother, Adla Dugan. This was a transformation in my life”. She adds: “We had around 500 sheep. We would take them out in the spring to the neighbouring pasture full of grasslands, flowers and stalks. We would build a house from goat hairwhere we would stay with the sheep until the end of the spring. We made this journey every year.

“In May, we would return to the village where we would shear the sheep’s wool. We sold the wool we didn’t need and stored specific quantities for ourselves, enough to make rugs for that year for the house and our needs. The process would to take the form of a celebration that everyone in the village took part in.

“My mother, Adla Dugan, would make at least two rugs every year and sometimes she made three or four rugs if there was a special and important occasion in the home, such as the marriage of a son or daughter, to cover their need for rugs in their new home.

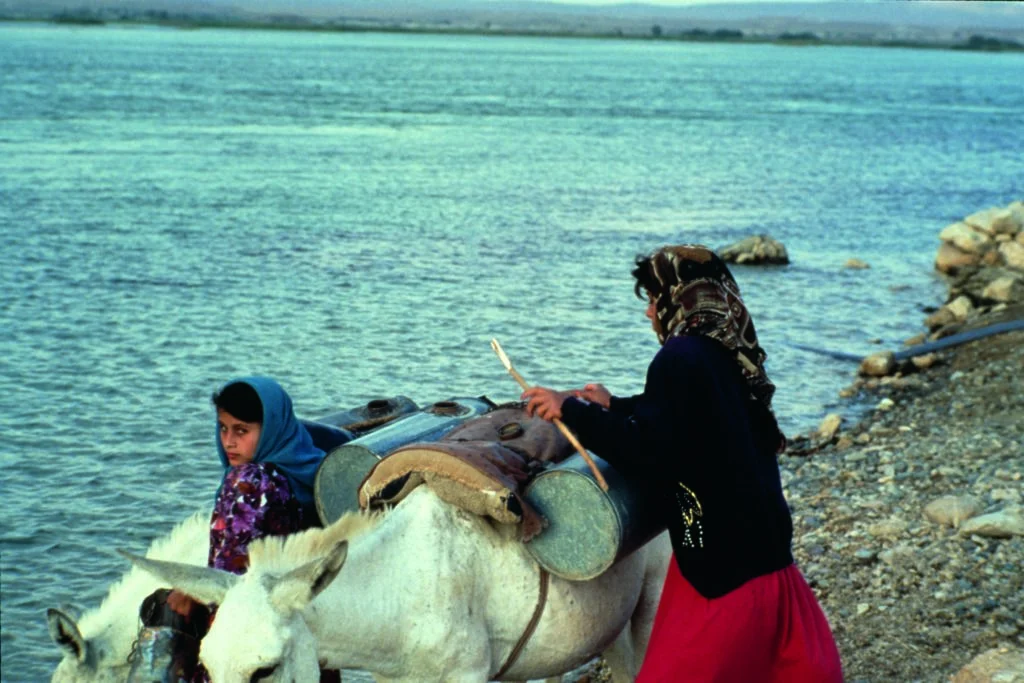

“The preparations would start at the beginning of the summer. First, we remove thistles, plants, sticks and manure from the wool due to the animals’ grazing in the pasture. Once we’ve finished cleaning the wool properly, we fill it into large canvas sacks (around 5 shorn sets of wool in each sack). Then we carry it on donkeys and go in small groups with the women from the village, on a set date and time, to the Euphrates to wash the wool in running water.

“When we get there, we choose a place on the river bank that is pebbly with a strong current that we call Al-Mouh. The current quickly removes the dirty muddy water (full of acid, fats and red soil from the wool) down to the river bed. We then soak the wool in water and taking turn with the others, we stamp on it continuously with our feet for around two hours.

“After that, we put the wool in clean water to give it one last wash until we can see it is pure white. We then take it out and place it on the dry pebbly shore and scrub it with our hands and feet and wring it to remove the water stored in it. We leave it on the shore under the sun for several hours to allow it to dry and settle so that it becomes lighter, making it easier for us to carry and take away with us.

“A little before sunset, we fill the wool into the same large sacks and go home. There, we take the wool out of the sacks and spread them on the clothes line for two or three days, depending on the temperature, to get rid of around 80% of the water and moisture in the wool. After it reaches the necessary level of dryness, we heap the pieces of wool on top of each other in a dry place. Heaping the wool helps to maintain 20% moisture in each piece. This process and moisture are essential, making it easier to separate the wool from the wool sheets when it is processed in the next stages into large skeins of yarn, some of which are coarse and some are soft, depending on the special tools used that we call “douk” and “mubram“. The use of the douk and mubram accompany specific social rituals; the women would gather at our house to help my mother Adla every day for almost four weeks. Each of them would bring their own mubram and douk”.

The douk is a thin twisted wooden stick that is no more than half a metre long. On one of its ends are two pieces of wood that are set one on top of the other; the length of one is no more than 10 cm and the width is 3 cm. In the first stage, the women use the douk to turn the wool into thick, coarse threads in large skeins.

In the second stage, the women start to separate each of the threads in the skein into five or six threads using the mubram to produce yarn that is soft, twisted and strong. The mubram resembles the douk exactly, except that the fixed part at the end of the stick consists of a single cylindrical component that is 5 cm long.

One rug that is around 4 m long with a width of 1.20 m requires twelve large pieces of wool with an average weight of 2.5 kg each.

“After the final stage using the mubram is complete, with one of her sons, my mother Adla Dugan would take the wool skeins on one of those Najjar vans that were made in Aleppo and were an important means of transport at that time. They were small three-wheeled vans with a driver’s seat and a small passenger seat and a square box for goods at the back. The skeins were taken to a famous weaver at the time in Al-Quwatli Street in Raqqa. He would dye and weave the yarn depending on the type of rug customers wanted.”

The weaver only made two of the types of rugs Raqqa is known for. The most famous and most expensive is the Ajami, which consists of a series of cubes and different geometric shapes with seven or more colours.

The other type is called Obaidi (the name of a well-known Iraqi tribe that has expanded its reach to the Syrian city of Al-Hasaka). It is cheaper than the Ajami and has a three-colour composition of red, white and black, in long alternating patterns length-wise from top to bottom.

The Ajami is considered to be very valuable and is linked to important, luxurious family occasions. As it is extremely expensive – it was around 75 Syrian pounds for one piece in 1964 (around 34 dollars at that time) -it was only used by middle income families on official feast days and other special family occasions, such as weddings, wakes and others to maintain its value and status for the owners.

Ajami rugs are also considered a luxury item in a bride’s trousseau and gives great value to the trousseau and are a source of pride for the bride before her husband and his family, when her family is able to offer one to their daughter. The bridal trousseau, or zihab in the local Raqqa dialect, are the personal items and gifts the bride’s parents give their daughter during her wedding and when she goes to her new home.

These rugs have not been made in Raqqa since the 1990s due to the abundance of rugs manufactured using machines for little cost and effort. Maryam says, “When I got married in 1975, my mother Adla gave me two Ajami rugs that I still have in my house. They are the only tangible memory that I have of my mother as they are a very precious heritage gift. I refused to sell them even in pressing circumstances. I also never use them in my house or for occasions so that they are not exposed to damage or wear”.

These rugs and other things, which the simple life has lost to machines and technology, are historical finds and artefacts whose owners are eager to hold onto and boast about having in their homes.

This is the most interesting link so far from my Courtalds Institute course as it describes a method of weaving which is similar to ones I’ve read of in North America , it would be good to be more descriptive of the cleaning method of the wool , for example is some type of ‘ carding ‘ instrument used , carding is an implement like a large hair comb made usually of bone or horn later these became mechanical but sometimes just ones fingers and visual cleaning might happen , perhaps someone who is a weaver could discuss and record for posterity this and what is known of dyes and how that too was done , Hank dipping ? Dying the fleece before spinning ? etc please help the daughter to let her memory’s surface and tell you as an on going conversation as her deepest youngest visual memories may take several years to unlock , Philippa Thomas England

Hello Philippa,

thanks for your comment. The comparison you made with North American weaving is very interesting. One can make a nice extensive research about that.

Although the following article doesn’t answer your questions about carpet making in Raqqa but we discuss similar techniques in Estibaliz Iracheta’s article on dealing with textile raw materials: https://syrian-heritage.org/from-animals-and-plants-textile-raw-materials/