by Dr. Sari Jammo*

The “Ancient Villages of Northern Syria”, or so-called “Dead Cities”, include more than 700 sites located in the Limestone Massif of the northwestern part of Syria, in the governorates of Idlib and Aleppo. The ancient villages stretch over a wide region on a series of limestone mountains extending from north to south (Jabal Samʿan, Jabal Barisha, Jabal al-Aʿla, Jabal al-Wastani, Jabal az-Zawiya). These villages were built between the 1st and 7th centuries AD and abandoned between the 8th and 10th centuries, when the population began to decline. Tchalenko (1953)** suggests that the region’s economy was specialized on olive oil production, which brought wealth to the region. The peasants produced olives on a large scale and exported olive oil to the nearby city of Antiochia and then to the Roman and Byzantine cities across the Mediterranean.

The Ancient Villages of Northern Syria are distinguished by many well-preserved ruins and architectural buildings, including churches, villas, temples, residential houses, cisterns, and bathhouses dating back to the Roman and Byzantine periods, which mark the cultural landscape in this region. Due to their uniqueness and archeological value, 36 ancient villages of the total sites were inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List in 2011 and set on the UNESCO List of World Heritage in Danger in 2013; they are organized in eight “Archaeological Parks”

.

The ongoing conflict in Syria that began in 2011 caused extensive damage to the Syrian population, their property and the cultural heritage, which is extremely important in human history. The country’s heritage properties are exposed to several threats such as destruction, looting, illicit trade, theft, and corrupt antiquity dealers, which leads to substantial damage or destruction of many important archeological sites and historical monuments.

The military operations forced many people to flee their cities and towns into safe places and many have settled in the ancient villages thinking that these archeological sites would secure shelter. Hence, the Roman-Byzantine buildings became a permanent residence to many families and the fallen stones in the sites were re-used to build shelters for those people. On the other hand, the lack of protection of the sites during the conflict and the poor economic conditions pushed people to look for treasures and hence illegal excavations increased and were undertaken in many sites. However, the greed and irresponsibility of some have caused systematic destruction to a number of sites through recycling the stones into carved or hewn blocks and selling them to build modern houses on a wide-scale compared to before 2011. On the other hand, we cannot hide the fact that the lack of awareness among many people on the importance of cultural properties and understanding that these properties belong to all Syrians, is a fundamental factor that should be considered.

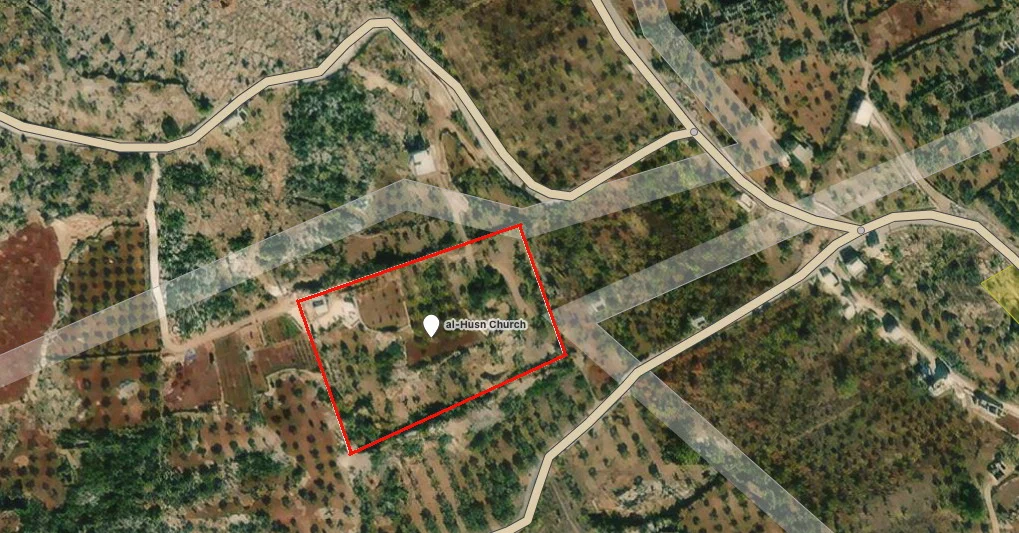

Al-Husn Church in al-Bara

In 2017, the University of Tsukuba surveyed documentation of endangered Syrian cultural heritage. They did this with financial support from the Agency for the Cultural Affairs of the Japanese Government and in cooperation with a civil society organization in one of Syria’s World Heritage Sites, i.e., the “Ancient Villages of Northern Syria”, the Idleb Antiquities Center. Due to the unfortunate intense conflict in the region, the destruction of many ancient villages of Northern Syria was reported. For example, severe damage to Saint Simeon Church in Jabal Samʿan and to al-Bara and Sirjilla, the trading centers in Jabal az-Zawiya, was reported. Therefore, a project was initiated to document the important buildings, especially churches, of this World Heritage Site using 3D modeling images. Al-Bara was selected for 3D documentation according to the upcoming information that buildings at al-Bara were severely damaged by bombing, theft and recycling of building stones.

Al-Bara is one of the major sites among the “Ancient Villages of Northern Syria” and contains at least five early churches. The largest and well-preserved (former) church is the so-called al-Husn church, located on the northern outskirts of the site. It is a typical basilica-plan church dating to the 5th century. However, the situation of al-Bara is not better than other sites in the region where locals extensively raided the archeological sites and systematically dismantled the building stones. A heavy machine driller likely used for digging the foundation of a modern house was observed bulldozing the remains of an archeological site!

One of the worst manifestations of destruction and intentional vandalism is the case of the basilica al-Husn. The building’s landmarks almost disappeared and became difficult to recognize. Unfortunately, al-Husn church was turned into a field for planting fruit trees, such as figs. The arched-shape remnants left standing in the eastern section are likely to collapse. Many parts of the building’s stones were recycled and relocated. The recycled stones were used to construct a stone terrace where a modern building was erected. Thus, we were unable to do anything to protect the building except taking some photos.

Locals Initiatives and Challenges

Many of the archeological sites of the “Ancient Villages of Northern Syria” are located near modern towns, and some of them stand on private land owned by local people. It has been reported that the sites located away from the eyes of people or inhabited villages were subjected to increased damage. Although most of the sites in this region witnessed destruction, positive local initiatives were reported. These initiatives illustrate the active role of local people in safeguarding cultural heritage.

For example, Farkiya is a famous inhabited ancient village near al-Bara and distinguished for its important Roman and Byzantine monuments such as the “Hammam Palace” and the “Hercules Castle” and other buildings with large mosaic floors. Due to this village’s significance, locals have formed a special committee for safeguarding the village’s ruins and historical monuments from looting and vandalism. They succeeded in monitoring the monuments of the village and filled up the illegal excavation spots when discovered. Hence, unlike neighboring villages, the ruins and monuments in Farkiya village are well protected.

In addition, the local council at Qalb Lawza village in the Aʿla Mountain has contributed to the safeguarding of the site. The site is famous for its 5th-century Byzantine church; however, it was subjected to illegal excavations, and it was used for some time as a sheep pen. The local council at Qalb Lawza, in cooperation with a local civil society organization engaged in safeguarding cultural heritage so-called “Idleb Antiquities Center”, have managed to stop these acts of vandalism. The church building was cleaned in cooperation with locals, the doors were repaired, and the site is now in good condition.

Unfortunately, many locals are not aware that Syria’s archeological sites and cultural properties are part of their national identity. This could be attributed to various factors, including lack of educational methods or educational materials on the importance of archeology of Syria in schools, lack of awareness campaigns for locals, the absence of society engagement in site management, and activities to encourage people to contribute in safeguarding cultural heritage. Nevertheless, locals have to share a sense of responsibility for safeguarding heritage regardless of whether they have received support from involved authorities or not through individual, or local-level, initiatives. I believe many people do not share the same sentiment, and this can clearly be seen in the various ways of vandalism of cultural properties. On the other hand, individual and local initiatives have not received sufficient support to be reinforced and spread in various regions under these severe conditions.

Here, I will briefly summarize the reason beyond destroying the archeological sites through two basic points:

1. The educational perspective: In general, Syrians did not receive cultural education at school about the importance of archeology and how Syria’s archeology is important for world history. On the other hand, most – if not all – archeological excavations carried out in Syria for decades did not contribute to raise awareness about the importance of archeology through educational lectures for locals during the excavation seasons. As a result, the negative consequences of inaction can clearly be seen in recent years.

2. Economic factors: Locals lived adjacent to these sites for a long time, but there was no financial benefit, although some of the sites are located on private land. Hence, many people tend to start investing in areas that are suitable for agriculture, which – from their perspective – are more useful to them.

Commenting on the situation of al-Husn church, it can be said that a basket of fruit, from the landowner’s point of view, is more precious than a 5th-century church. Hence, the landowner may claim an extra price for his crop because it comes from a 5th-century (or maybe older) land plot.

*This article is based on a study funded by a research fellowship from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), KAKENHI Grant Number 19F19004.

**Tchalenko, Georges, Villages antiques de la Syrie du nord: le massif de Bélus à lʼépoque romaine, 3 vols., Paris 1953–1958.

Featured image: General view of al-Bara ruins | Eva Haustein-Bartsch (CC-BY-NC-ND)

Published by Sari Jammo: Sari Jammo is a postdoctoral research fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science at the University of Tokyo. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Tsukuba, specialist in ancient Near East Archaeology, and interested in safeguarding cultural heritage in conflict zones.

I am the holder from Ten thausands of Fotos from the Dead Cities.

I worked with DGAM Damascus together, with my Syrian residence and my Syrian car I was independent in moving to anywhere.

My name in the Directorate general of Antiques in Damascus is well known.

Dr. HAMOUD Mahmoud was my last manager in Damascus.

In my facebook Account

Elvira Portugall

in Fotos Alben

you will find a lot of Syria Foto reports.

Now I Am in Greek, awaiting better life conditions in Syria.

I would be happy, to do all my foto documentation in the German database.

I worked in additionally with the Tchalenko books and did do actual fotos before 2011.

Major Balatz, Hungarian Chief Archaelogist, supported me with hints and tipps.

I hope, to get any response from you.

I am German.

Kind regards

Elvira Portugall Tartus