Ezidis (often known as Yazidis) are an ethnoreligious group living mainly in northwestern Iraq, southeastern Turkey, north- and northeastern Syria, Armenia and Iran. The main settlement area is in the Sinjar and in the Shaykhan region in northwestern Iraq.

Ezidism is a monotheistic, syncretic religion, having roots in a pre-Zoroastrian Iranic faith. The religion is based on transmission through oral traditions. Their prominent place of worship is the shrine of Shaykh ʿAdi ibn Musafir at Lalish in Kurdistan/Iraq.

The Ezidi people have been marginalized and were repeatedly religiously persecuted.

Anne Mollenhauer interviewed two young Ezidi women, Basma Aldakhi and Sara Hassan, who had to flee from their home in the Sinjar region before the invasion of the so-called “Islamic State”.

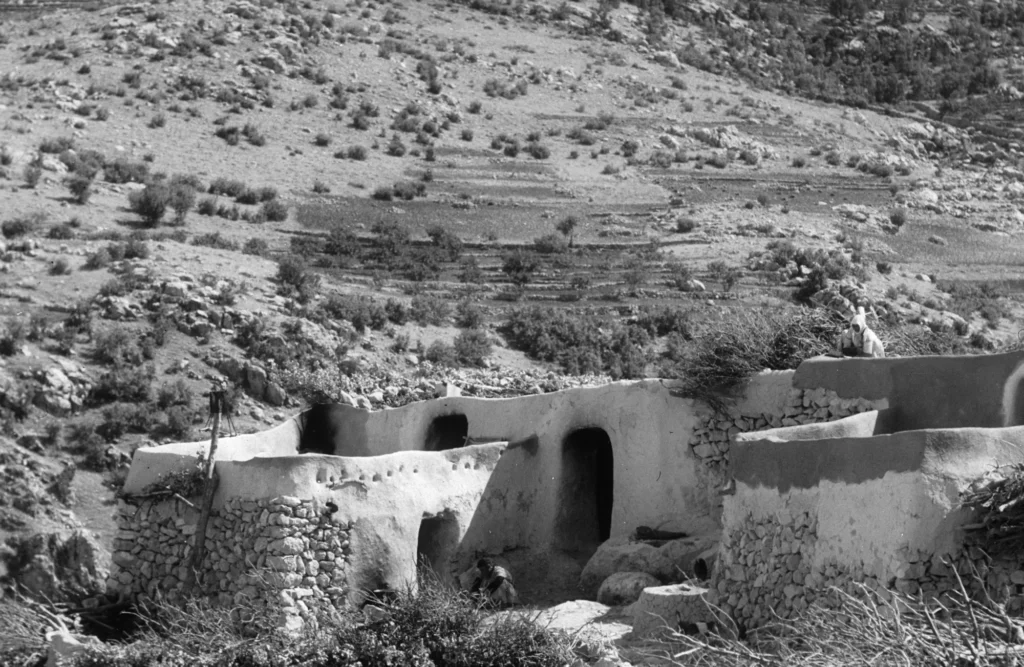

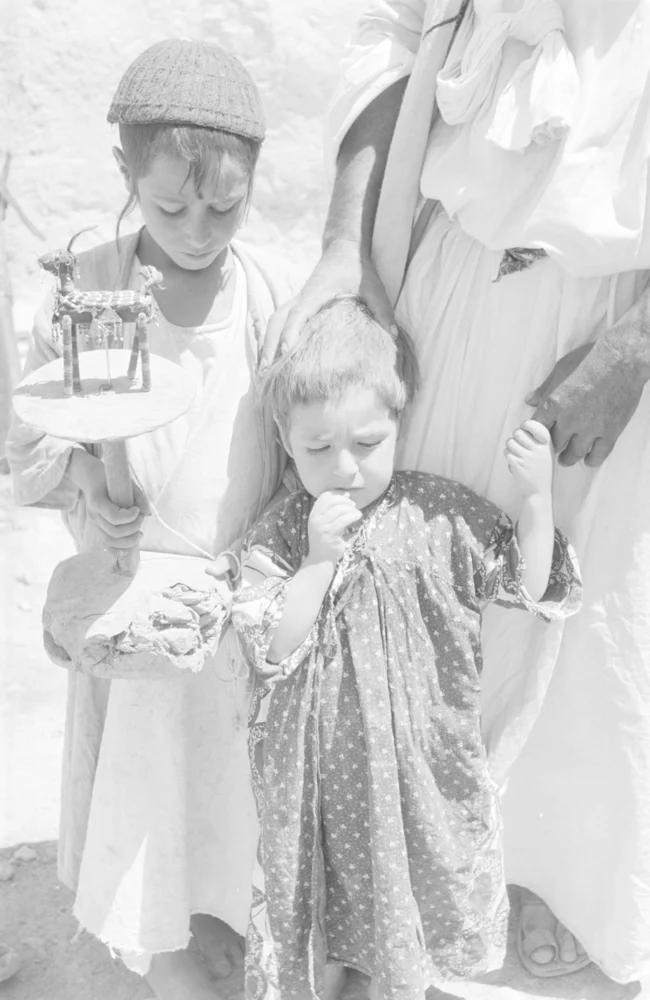

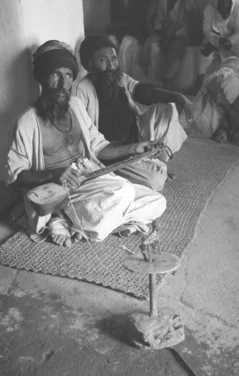

The interview is illustrated with photographs by the geographer Eugen Wirth, which he took in 1953 during a long journey to the Jabal Sinjar. They thus represent a unique source of the vanished world of the Ezidis.

Anne: Where did you live before you had to flee?

Sara: I lived in the Sinjar area, in the collective town of Hateen.

Basma: I also lived in the Sinjar area, but in the collective town of Khana Sor.

Collective Towns

In 1975 the Iraqi government under Saddam Hussein started to destroy Kurdish and Ezidi villages and their local identity by forcing the village population to live in collective towns, the so-called Mujammaʿat. Under the pretext of modernization and access to health care and schools, the historic villages had to be abandoned. On the northern and southern foothills of Jabal Sinjar, 11 collective towns were erected, where the Ezidis had to settle.

Anne: Which language do you speak?

Basma: We mostly speak our dialect from Jabal Sinjar, Kurmanji, a Kurdish dialect. But we also know Arabic very well, which we learned at school, and the Kurdish Badini dialect, since we live now live in Dohuk.

Anne: So you did not live in a traditional village?

Basma: No, never, but my parents lived in the village of Karsee.

Sara: My family came from Bara, which is near the Syrian border.

Anne: Do you know what the traditional houses looked like?

Basma: The traditional houses in our area were made of rocks and mud, and they contained one room, like tents. Since we depended on the fruits which grew in our area, drying and storing of dried fruits and vegetables was very important for our parents and grandparents.

There was also a particular type of house dug into the earth. The roof was on the same level as the soil, so these houses could not be easily seen. They were perfect for hiding in times when we were persecuted.

Sara: Some people in our area, in Bara, near the Syrian border, were living in tents made from goat hair. They were black. (Anne: Like Bedouin tents? Sara: Yes)

Only the notables had houses with more than one floor, consisting of two floors and a basement made of rock and mud. I heard of one man living in the nearby caves. He used three caves: one for living, one for weaving and the third one for tailoring.

Anne: Are there any specific features which make an Ezidi village recognizable?

Basma: The typical Ezidi house has a very low door, so you must bend your head while entering it to signify respect and worship to god. Another important feature is the threshold. No one should step on it when entering the house; you must put one foot on the outside and the other inside without touching the threshold. You will also find the same concept in our temples, e.g. the temple of Lalish, which is the holiest place in our religion. Even when the door is of average standard size in a modern house nowadays, some people still bend their head to worship god and as a cultural tradition.

Anne: Are there specific traditional dresses?

Basma: When a girl marries, she wears a white dress and a shawl or red piece of cloth on the head. Grooms do not have special garments; they wear their regular clothes. When someone in the family dies at the time of the marriage, the bride should not wear these ceremonial dresses but dress simply and modestly to show her sadness.

Sara: The most dominant color for our ordinary dresses is white, for both men and women. A black jacket is worn on top, sometimes with red stripes on the sleeves. The men have white galabeyas and no collars but round neck openings. So, when I see a man in that dress, I immediately know that he is from our community.

Basma: Another special dress is worn by the fuqara, the poor. This so-called kharqa is in a dark brown-black. The cloth was dyed with walnut juice and then dried on a walnut tree all night during a full moon. The fuqara (sg. faqir) are very poor but the most honest and respected persons in our community. Only people who had lived an impeccable, simple life, had not harmed anybody, committed no sins and lived according to our religious rules could become a faqir.

A faqir is the most respected person in our community. If there is a fight between Sara and me and the faqir renders a judgment about the conflict, we will follow his decision. Everyone has to follow the decision of the fuqara or what they are doing, even if they were to beat you. If a faqir does anything wrong, the community takes the dress from him, which is very shameful. When he affiliates with or supports one party more than the other or if he supports someone unjustly, the dress is also taken from him because he has lost his neutrality. The tasks of the fuqara are cleaning and serving in the temple, they are always there. Kissing the upper sleeves of their dress is a kind of blessing.

There were many fuqara in our community in the past, but their number has declines more and more today. It doesn’t seem easy to behave in such a perfect way today.

Anne: You mentioned Lalish before, the most important worshipping place of the Ezidis. I saw on my way from Dohuk to Erbil Ezidi shrines on and beside archaeological talls. Is there a special connection between ancient Mesopotamia and the Ezidi religion? Or did you ever hear of the ancient Babylonian god Nabu?

Sara: Yes, our religion goes back to those old times. In our religion the sun is the holiest element, because it is the source of life. We pray to the sun when it is rising and when it is setting down. The beginning of April is the most important religious feast, the “red Wednesday” (chwar shamma sur). But I don’t know if there is a special connection to the site of the tall and the shrines. The shrines are built on places where holy persons died or were divine person stayed and were built as commemoration place.

Lalish is the most important Ezidi temple in the world.

Basma: I never heard of a god Nabu in our religion. But maybe we pronounce it differently, so I do not recognize him or know it.

Anne: What does a temple look like?

Basma: I will show you pictures, then you will know. You see, these conical folded domes as are considered typical for our temples.

Sara: In Lalish you will find the same element as in the house I mentioned: this low door and a high threshold. Beside the door is a depiction of a black serpent carved into the stone. Some people kiss the serpent before entering the temple because it is a divine creature which should not be killed. They also kiss the threshold and the side of the gate.

Anne: Are there many other temples here in the region?

Basma: O yes, almost every village or town has its own temple, but Lalish is the most important one in the world.

Anne: Has Daesh destroyed many of them?

Sara: Many, many, many. In the Sinjar Region alone, about 81 are recorded to have been destroyed.

Anne: And are they going to be restored?

Sara: Some communities started to rebuild the temples, but then there was a decision that supporting funds should not be used for the restoration of temples but for the support of the people. Restoration can be done at a later stage.

Basma: Many people still live in terrible conditions, and many orphans, etc., need support. Anyhow, some temples are restored by individuals.

Anne: During your religious ceremonies, does music have a specific role?

Basma: Music is an essential part of our rituals. Every ritual is performed with music. The dancers have a kind of religious background. We have many songs and tales about our religion transmitted through music. They are communicated in an old dialect, so I cannot tell you the exact story they tell. But I will play some music so you can get an impression.

Sara: One story I know is about the persecution of someone in the south who fled to the north. There are so many different oral traditions about our culture since, nowadays, Ezidis live all over the world. I know one, for instance: it is about the Ottoman wali of Mosul Hafiz Pasha, who launched a genocidal attack on Sinjar, killing many, many Ezidis. There is a poem that relates to and tells the story of Ezidis’s suffering.

Anne: Do you have specific fairytales which your parents of grandparents tell?

Basma: No, we don’t have this tradition. The old songs speak about our history and events, but, as I said, they are in an old language. We cannot understand many of the words, I have to ask the older adults what the songs are saying.

Anne: Is there anything you would like to tell us about your culture?

Sara: When we marry, the family keeps the mother’s name, not that of the father, as an expression of respect for the women. Ezidis are not allowed to marry someone who is not Ezidi; otherwise, they will not be Ezidi anymore and will be expelled from the community. This happened under the rule of Saddam Hussein, when many Ezidis converted to Islam and later wanted to reconvert to Ezidism. But they were not allowed by our religious leaders. That’s one of the reasons why we have become such a minority. It was a crucial step for us when Baba Shaykh, our religious leader, allowed those girls who were raped and enslaved by Daesh (IS) to return to our community and be reintegrated. This was a significant step for us.

Basma: Once, I met a person from the south. He was astonished when he met me and said: “I thought Ezidis just wash themselves every 40 years!” Another person said that she does not shake hands with Ezidis because we are dirty. There is so much wrong and bad information about our Ezidi culture and religion spreading around, and I want people to know the right things and not these harmful lies.

Persecution under the IS rule

The end of the Iraqi war in 2003 and the chaotic situation of the Syrian war since 2011 encouraged the rise of terrorist groups such as al-Qaida and the so-called “Islamic State”. On the 3rd of August 2014, the “Islamic State” invaded the Sinjar region intending to exterminate the Ezidis. A genocide of the Ezidi population occurred. At least 10.000 people were killed. Thousands could escape – primarily to Iraqi-Kurdistan, where many still live in refugee camps. Others managed to flee to European countries, especially to Germany.

Anne: Do you have contact to the Ezidi communities in Syria or other parts of the world?

Sara: Yes, of course. My father tried to flee to Syria when Saddam Hussein persecuted him, but he did not make it. He was killed before I was born.

Basma: My father also had contacts in Syria and went there when we were threatened. He returned when the Iraqi government declared an amnesty. Some Iraqi Ezidis are still in Syria, cousins and relatives, and we still have contacts there.

Sara: I am participating in an international chat group of Ezidi women. When we talk about our culture, I sometimes feel they are talking about something completely different from what I know to be our culture.

Ezidi women and girls

Over 6000 Ezidi women and girls were kidnapped, raped and enslaved by IS terrorists, and they were captured to work in the households of IS-terrorists and often sold from one family to another. Since IS fall in Iraq, Ezidis women and girls fled or had to be “bought” to return to their community. Nadia Murad was one of the former victims and dedicated her life to fighting for her fellow sufferers. She received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018 (together with Denis Mukwege) for her efforts.

Featured image:

The Ezidi mausoleum of Sitt Zaynab (from the time of Badr al-Din Lulum Atabeg of Mosul, 1233-1259) in Balad Sinjar on the slopes of the Sinjar Mountain range, 1953 | Museumfor Islamic Art in Berlin, photo: Eugen Wirth (CC-BY-NC-SA)