by Hasan Ali

Hasan Ali invites us to discover Palmyra/Tadmor from a local perspective by recalling childhood adventures and the testimonies of the elders to draw personal maps of cultural meanings and social values. It is an intimate yet collective journal of memories, scents and Palmyrene features and characteristics. As a Palmyrene archaeologist Hasan Ali was very much affected by the destruction, looting and vandalism of heritage in his city, he started to collect memories of Palmyras former residents as a documentation project.

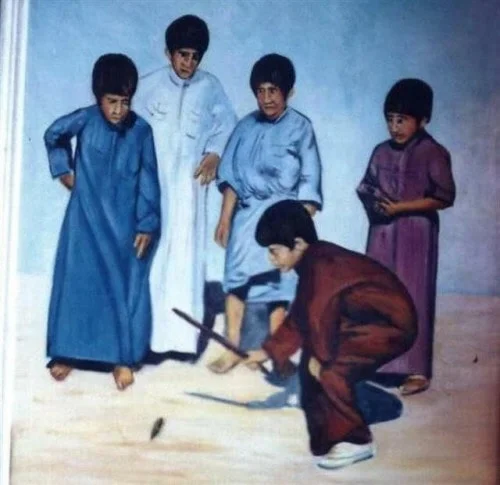

“My homegrown friends with whom I used to play hah (a traditional boys game) left” – is a local proverb to express nostalgia to childhood innocence and longing to home place familiarity. Losing home was our experience as inhabitants of Palmyra/Tadmur in recent years. When we were young, we heard this proverb after our parents. We could not understand its meaning until we grew up and particularly, when we were forced to escape. Indeed, all my former neighborhood children left our home town, spreading around the globe. We were separated from each other in different countries, and Palmyra/Tadmur was left alone, laying in ruins, with everyone left but the military.

In Tadmur, my fellow kids and I used to play in the streets of the central district close to the Sports ground of Ash-Shabiba (a governmental organization targeting youngsters) and close to Tadmur’s infamous prison’s eastern wall; we feared getting too close to its walls without thinking about the fact that people were locked up there. For the hah game, we gathered short sticks and one long stick, which we took from olive or pomegranate trees wood. We used to put the short sticks (25 to 30 cm) at the edge of the sidewalk directly into the earth and then hit them with the long stick (approximately 100 cm) to make the short one fly as far as possible. Whoever could make it reach further was the winner.

When Abud Shehab, one of my friends, felt hungry, he used to run home and roll a sandwich of goat labne (a very thick yoghurt cheese) or a homemade spice mixture called z’atar (thyme) on the bread. This was baked either by the modern automatic “Oven De Gaulle” or the more manually working “Oven Sulayman”. The latter was already greased with semne (sheep ghee). This semne is prepared using the jiff, a goat skin-bag in which yoghurt is shaked to extract butter and later ghee from it. For us, a jiff was used by Bedouins of Mount Al-ʿAmour, which is about 50 km to the north and is also called Mount Abu Rajmayn. We ran behind Abud to get also a rolled sandwich prepared lovingly by his mother, Auntie Hind.

Palmyra/Tadmor:

In Arabic, the name Tadmur refers to both the ancient and the modern city. In German and English, a linguistic distinction is made between the ancient city of Palmyra and the modern city of Tadmur. The caravan post of Tadmur in the Syrian Desert is already mentioned in ancient Near Eastern sources of the 2nd millennium BC. When the new town was built north of the antique ruins under French mandate rule at the end of the 1920s, the name Tadmur stayed. Before the IS invasion in 2015, about 80,000 inhabitants lived in the modern town Tadmur.

The Afqa-source and its oasis

We were eagerly waiting for the holiday, especially during the hot days, to go out with our family or friends and swim in the sulphur waters which are fed by the Afqa spring. This spring is the source of life of Palmyra/Tadmor. It is the reason for its existence, and was the main water supply for agriculture in the oasis. The spring water flows in a curve to the palm grove, and passes through some extension pools. Men used to swim in the men’s pool (hammam az-zilm), which was about two meters deep. In one of the interviews with Palmyrene inhabitants living in Turkey, Mr. Riyad al-Jarallah, a former official of the water administration, described the hammam az-zilim as an open section around which terraces of limestone were cut into the rock for bathing and recreation. During the French mandate a swimming pool (of ca. 7 x 20m) had been built on top of it, which was removed when the Meridian Hotel was constructed in 1985. The Afqa water continued to enter a concrete room built in the 1920ies. It belonged to a mill that was set up there to grind grain using the water flow power. The mill was removed in the 1950s, but the concrete room was reused as a pool for women.

As kids we loved to swim in the so-called Shari’a Pool, where the water was shallow. Its name “Shari’a Pool” preserves the memory of a Shari’a school which Shaykh Muhammad Shams al-Din (known as Shaykh Shakas) had established there in the 16th century. The school has disappeared since a long time but as the pool is a distribution basin for the 3 main canals that irrigate the oasis it survives up to now.

The Afqa spring dried up in 1994 due to the drilling and explosions for the Meridian Hotel construction next to the cave, representing a rocky cavity from which the spring water flowed. These explosions fractured the source rock. In 2021, I heard that the Afqa spring was giving water again.

After swimming, we would get dressed and continue walking between the orchards of the oasis, which is as old as the Afqa spring water and is famous for its abundant palm, olive and fruit trees. The promenade through the alleys of the orchards was out of this world and cannot be easily erased from the memory as it represents so many delightful feelings. The passage between mud walls was sometimes two meters wide. Alleys were aligned with waterways coming from the Afqa spring, operated by irrigation motors like Andrea and Black stone. Their sounds cheer in every ear of a Tadmuri till now. I remember that some alleys couldn’t get the sun due to the density of palm, olive and pomegranate trees. People used to pass these alleys walking, biking or riding a cart with a donkey or a three-wheel-draisine, which we call tartayra. In Tadmur people knew each other, and used to exchange jokes and offer each other some dates and pomegranates they picked and put up in the market for sale.

Tadmuris and their town

The inhabitants of the old village of Tadmur, which was situated in between the ruins and inside the Temple of Bel were forced to move to a newly built town further north by the French mandate administration. Although the place for the new settlement north of the ruins carried the old name adh-Dhahira (still in use among elderly residents) the new town got the historic name Tadmur. The former director of the technical office in the municipality of Palmyra, the architect Ahmed Al-Agha, explained about the relocation of the people: “The reason behind the transfer of residents from the ancient village to Tadmur adh-Dhahira was to enable the French occupation authorities to uncover the Temple of Bel and the monuments of the ancient city of Palmyra. So they decided in 1928 to relocate the residents from their homes within the Temple of Bel and its surroundings and move them to the new place. The parcelling and road network was outlined by the French authorities.

During my youth, while still studying in secondary school, my friends and I used to wait for school time to end so we could bike to the archaeological area to play football or run there. Once I was biking down the citadel hill of on an earthy way towards the northern tombs and Camp of Diocletian, and a friend was sitting behind me, and out of a sudden, I felt the bike was way lighter to discover that my friend felt and rolled the way. Luckily he had only superficial wounds, but he reminds me of this accident until now.

Palmyra Ruins

Sometimes we used to enjoy sitting on the roof of the tomb towers. I used to daydream back then about my future as an archaeologist and the great books that I would write about the ancient history of what I could see as buildings around us. Sometimes I imagined how I am bringing back the widespread ruins to how they looked in the time of our ancestors Odaenathus and his wife Zenobia and that we modern Tadmuri residents could come back and live there.

After a few years, I realized my dream to study archaeology, and I graduated from Damascus University. From 2007 to 2015 I worked at the Directorate of Antiquities and Museums in Palmyra. My colleagues Hassan, Muhammad, Najem, and I often ran before sunset to arrive at the fortress hill of Qalʿat Ibn Maʿn and enjoy the sunset shades colouring the archaeological monuments with the magical purple in the evening. Also tourists liked to climb up the hill to enjoy the beauty of this time of the day.

Back then, night time in Palmyra was more eventful than its day time. The summer weather gets so gentle at night, and the breeze becomes cool and fresh. Families and friends used to gather at night in the courtyards of the houses during that time. In winter, men enjoyed the hospitality of the guesthouse (madafa or manazil – as locals call it); they gathered around the warmth of the diesel or wood-fired heater, the soba.

Crisis, invasion of ISIS and our escape

My dreams about Palmyra faded with the outbreak of the conflict in 2011/12 that caused the displacement of 60% of the population. During this time we were looking for security for our families and enough income to survive, so I took a second job in a clothes shop.

When ISIS invaded Palmyra city in 2015, life became a hell. We had to flee my beloved town running from the inevitable death. I escaped with my family first to Gaziantep in Turkey, later to Istanbul. Suffering came in different shades in the new country. We had to learn Turkish and to accept the Turkish habits and ways of living. First I worked as a teacher of Syrian history and a trainer for Syrian heritage crafts for Syrian refugee children. In 2016, with the support of the German Archaeological Institute in Istanbul and funded by the German Gerda Henkel Foundation, I could work as an archaeologist and later as an oral historian for my home town. I started my new work by documenting essential aspects of Palmyra’s heritage and its surroundings and the lifestyle of Palmyrene people. I collect memories from events like the moving from the old village to the new town, periods of power fluctuations etc. in the 20th and 21st century, as I consider it necessary to reconnect the Palmyrene diaspora community, protect the knowledge about the modern history of Palmyra, and give a voice to the people in the diaspora. In 2020 we initiated “Palmyrene voices” and launched an income project with traditional handcraft products from Tadmur.

In my opinion, it is unlikely that the people of Tadmur will be able to return home in the near future. But we want to go home to work with experts to ensure the preservation of historic Palmyra for future generations. A way must be found to preserve knowledge and heritage to transfer it properly from grandparents to grandchildren. The best way is by bridging the gap created by the massive exodus of Tadmuri residents by recording and analyzing the collective memory of the Palmyra refugees in their diaspora, so that they can share their stories and memories with their children and the whole world. Our hope remains, that one day we can return to our home Tadmur/Palmyra. Hoping, that future generations will keep this hope.

Featured image: View to historic Palmyra in the foreground with the modern city of Tadmur in the back and parts of the oasis in the west, 2002 | Photo Peter Heiske (CC-BY-NC-ND)

Published by Hasan Ali: Hasan Ali is a Palmyrene historian and archaeologist who holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of Damascus. Since 2016, with the help of the German Archaeological Institute in Istanbul, he is documenting the heritage of Palmyra and its surroundings in the 20th century and the present.

https://palmyrenevoices.org/