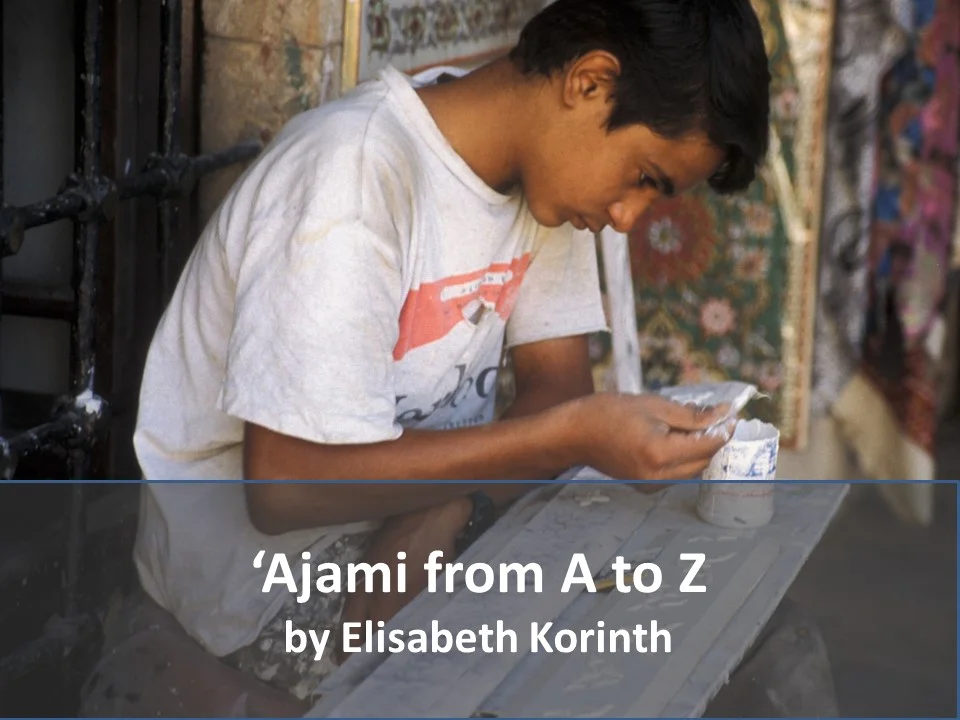

by Elisabeth Korinth

When working with the craft of ‘Ajami, the quality of the decoration and the precision of the execution depends to a great extent on the craftsperson and his or her practical experience. Creating ‘Ajami is not the work of one person but a whole workshop of workers. Families who have specialized in this craft often look back on a long history of experiences that have been passed down generations.

Depiction of a peacock on the decorated wooden panels of the Aleppo Room (© Museum für Islamische Kunst der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Photo: Georg Niedermeiser)

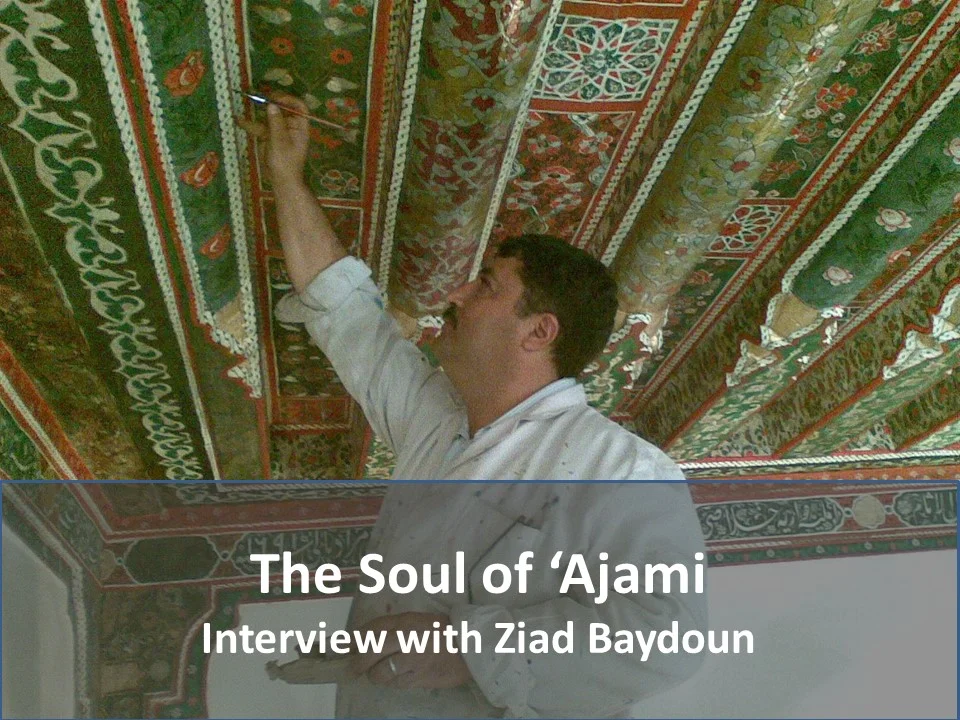

These processes have been optimized over time through generational transmission. The importance of artisan training should therefore not be underestimated. Symbolic importance is also placed upon specific teachers of the craft. In Syria, crafts are often associated with a grandmaster, a prestigious reputation earned through his experience and the quality of his work. This position was increasingly recognized starting in Ottoman times, and was tied to a set of religious and ethical criteria that addressed the master´s dedication and devotion, as well as his character. These grandmasters of craft were called Sheikh al-Kar or Sheikh al-Maslaha. This is an honorary title, which translates to the “Master of the crafts industry.” “A Sheikh al-Kar”, explains the Syrian artist Ziad Baydoun,“ is someone who can do the craft from A to Z on their own, starting with the design, cutting wooden panels to the last brushstroke.” A grandmaster needs to know how to blend the colours and how to experiment with them. The story of the ‘Ajami craft therefore not only tells the history of a traditional craft. It further reveals underlying historical concepts of how a craft was practiced a few hundred years ago, when each craft was governed by one grandmaster.

Having learned the craft from a renown master still means a certain prestige even though it is no longer an official position and its political and religious role has since faded. In general, anyone can learn the craft when employed in a workshop. However, crafting tricks and corporate secrets are usually kept within the family or business. On the one hand, this ensures the family business will be successful. On the other hand, it creates barriers for outsiders to learn the craft. The craft is on the verge of being forgotten. In an interview with the Interactive Heritage Map of Syria Project, Aliya Alnuaimi, a female artist, talks about the difficulties she encountered in the beginning of her work due to the craftsmen being unwilling to share their knowledge.

Layers of meaning

While the painting itself is considered a luxury craft, the meaning of the various motifs and images go deeper than the colours used, expressing a symbolic language with hidden messages, often enriched by sophisticated calligraphy work.

Illustration of the prevention of Abraham´s sacrifice by an angel on the wooden panels of the Aleppo Room (© Museum für Islamische Kunst der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Photo: Georg Niedermeiser)

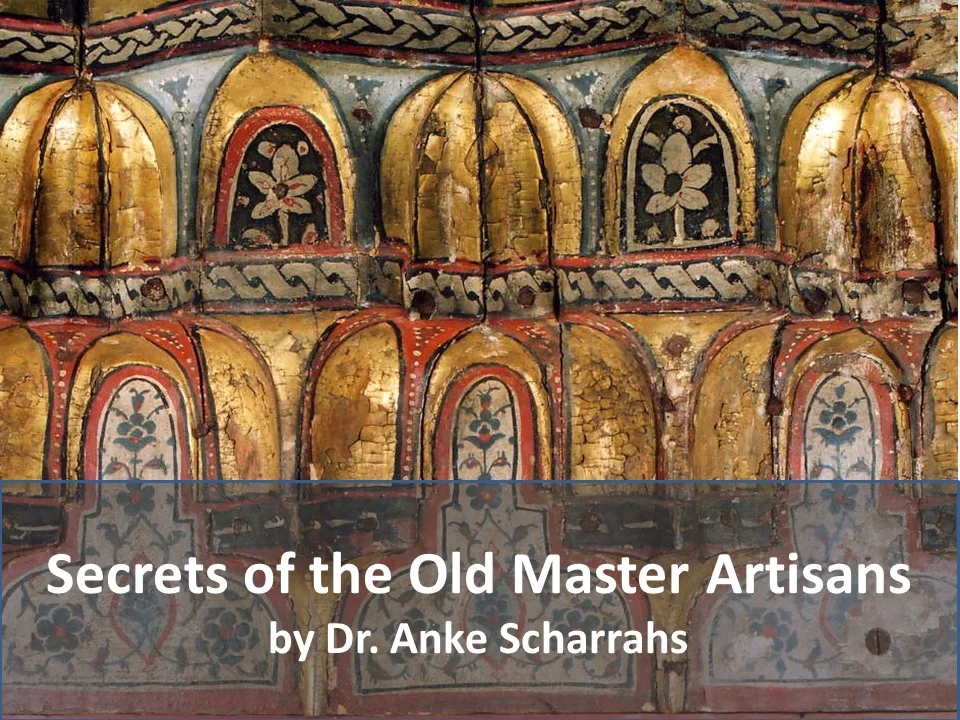

The Aleppo Room, located in the Museum for Islamic Art in Berlin, is an exceptional example, especially for its various layers of meaning embedded in the imagery of the decorated panels. This includes a rich variety of different kinds of flowers, geometrical forms and fruits. The paintings show off a mix of religious sceneries such as the biblical last supper, Abraham sacrificing his son Isaac, and a then contemporary artistic depiction of popular known Persian and Arabic literature, such as the love story of Layla and Majnun. These elements are enriched by East Asian mythical creatures: dragons, phoenixes and the so-called Qilin (a mythical creature with a scaly body and deer horns).

Even motifs that appear to be only a decorative element entail stories that can be misunderstood at first glance. Rami Alafandi has dedicated his research on the origins and development of motifs on sophisticated ‘Ajami work (read his article). According to his research, tulips often symbolize God, while roses appear as a representation of the Prophet Mohammad.

The craft today

In present times, the paintings are still enriched by the personal touch of the craftsperson, sometimes making the craft to a very personal expression of the artisan´s creativity. Each workshop has a unique composition style for an art piece. “I like to include hidden messages in my pictures,” says Ziad Baydoun, a craftsman from Damascus currently working in Malaysia. “On the one hand, they help me to recognize my work by integrating my signature. On the other hand, the work becomes something unique this way.” In an interview with the Interactive Heritage Map of Syria project, Ziad Baydoun tells his personal story of how he ended up working in Malaysia trying to raise awareness about a craft that is on the verge of being forgotten.

Experimenting with new types of material and colours are also part of the development of this craft. “The most beautiful experience for me was introducing oil colors in this work, which I previously used with oil painting”, remarks Aliya Alnuami. “This distinguished my work and added another layer to it, in the sense that no one else can make exactly the same piece, in its colours and gradations.” But in fact, the workshop in the Al-Azm palace had already used oil colours in the 1920s, possibly influenced by French workshop leaders of the time, explains restorer Dr. Anke Scharrahs. The discussion of what counts as authentic and traditional and what is modern day practice often inflames debate. In the end, no workshop is really following the old techniques; contemporary works still differ from the ones fabricated during Ottoman times. They nevertheless reflect and commemorate the splendor of a uniquely Syrian craft that has been practiced for centuries, one still valued by many people around the globe as their cultural heritage.