In this series we display personal stories of places (historical monuments) in Aleppo city, told by people who had a special bond with the place. The aim of this series is to highlight the intangible aspect of heritage places in Aleppo, and to communicate the inclusion of memory in reimagining and rebuilding a place through its people.

These contributions are part of the joint efforts of the Interactive Heritage Map of Syria Project along with the Aleppo Heritage Catalogue Project, which seeks to document the history and architecture of historical monuments in the city of Aleppo.

Explore here with us a personal view on the history of Aleppo.

Bab al-Faraj clock

Ahmad Anis

October 2019

Between the year 1993 and 1994, when I was in fifth grade, I would pass by Bab Al-Faraj clock-tower every time I head to al-Jadida quarter to visit my uncle, Adnan Faris, who used…Read More

October 2019

Between the year 1993 and 1994, when I was in fifth grade, I would pass by Bab Al-Faraj clock-tower every time I head to al-Jadida quarter to visit my uncle, Adnan Faris, who used to repair old clocks. He was very well known for having most of the spare parts of clocks, and that he could repair the most difficult and complicated clocks out there. One time, a foreigner brought a rare broken clock from Europe that once had belonged to the collection of the last Russian Caesar, to be repaired in Aleppo in the hands of my well-reputed uncle. Those rare mechanical parts have always fascinated me. Every time I walked past Bab al-Faraj and saw the clock out of order, I would aspire to repair it and think about how I could restore it back to life one day when I grow older.

In 1995 official authorities cleaned the tower’s stone facade and fix the broken clock, but after a while it stopped again. Since I always had the will to repair it, I applied to the municipality of the old city when I was 16 years old, as my first attempt to work on the clock. I got the approval to go and check it. When I entered the place it was a great joy for me to see this unique treasure from the inside for the first time. A place ordinary people cannot visit, or even touch. My joy was immense, but accompanied by greater sadness due to poor former attempts to maintain or repair it. The clock relies primarily on weights that have a specific and precise scale to rotate its different sections, including the one that rotates the hands, the mechanical section of the clock through which the bell rings according to the number of time, and the melody section through which several bells ring a certain melody. It was not checked before why the clock kept stopping or where the error lies, as the attempts were not based on studies. When a fracture occurred in one of the gears and was replaced, the reason for the break was not really taken into consideration, and therefore it kept breaking and had so many errors without them being solved.

The minute you step inside the clock tower and start ascending up it feels as if you travel back in time, taken into another era, hundred and twenty years back. When you look at the technique of making the clock at that time and touch its mechanical parts, it transports you to another world. The smell of oil and wood cannot be forgotten and your sensation is indescribable. I was standing under the tower and imagining how the lights would look like, how would the clock hands turn, and what the bells sound like?

I began to restore the clock but my work was not complete. During this process I started having nightmares that someone would come to repair the clock only to complicate and cause malfunctions that lead to a fatal failure which can never be fixed. I had my attempts to continue repairing it, but I failed as I was still very young for such an experienced job, though I had repaired many clocks in most Syrian cities, including the clock of Deir Sednaya, the clock of the city of Salqin, the clock of the train station in Aleppo, and the clock of the Hijaz station in Damascus. The latter was a very complicated one because it is the parent clock (1) associated with all clocks of train stations connecting to the last station in Madinah, Saudi Arabia. It has a very precise mechanical and electrical magnetic work attached to it to take the timing in order for all clocks to work together and at the same time along the path of the train line.

As for Bab Al-Faraj clock, I was always accompanied by a constant nightmare, in which I wake up at night after disturbing dreams that the clock was destroyed by war, stolen, removed, or that something else was built in its place. My first visit at the end of the war in Aleppo was to go and see the clock tower. My heart was reassured when I found it in its place, un-tackled. Only some copper pieces were stolen for their material value. I later compensated the pieces. I proceeded to repair the clock at the beginning of 2017 with the rapid approval from the city’s governor. It was a volunteer job, but I was in an age (37 years old) where I was able to take full responsibility for that work. I took the work seriously, and I fixed it with precision. The bells started ringing again – a sound that had been forgotten by the city dwellers. An elderly man once told me the clock only rarely worked in the past 55 years, and its bells were never heard.

At half past five, at sunrise on Eid Al-Fitr, in 2017, I completed my work in the clock. I went out of the tower and stood in the square, pondering it from below. At six o’clock, the sun rose up shining on its golden hands brightening the façade, and the bells rang for the first time. My joy was immense! I will never forget this moment. Then I went home and took a deep sleep rest. On the third day of Eid, I went to visit the clock with my family. It was four o’clock in the afternoon. When the bells knocked the children started dancing, joyful to hear the sound. My dream has been fulfilled for this important monument as I left a personal impact and had a hand in its maintenance and brought it back to life. I hope Aleppo will remain in its original beauty without deformation, and that the clock will continue to work regularly and not be tampered with in any way.

Ahmad Anis

(1) Damascus was the first stop of the Hijaz railway.

Al-Zawiya al-Hilaliyya

Ruba Rostum

August 2019

I am fond of Aleppo, not only of the city’s historical monuments, but also of its social and human heritage. As such, I got to know al-Zawiyya al-Hillaliyya as a place that has been…Read More

August 2019

I am fond of Aleppo, not only of the city’s historical monuments, but also of its social and human heritage. As such, I got to know al-Zawiyya al-Hillaliyya as a place that has been holding dhikr (Sufi ritual prayer) sessions for eight hundred years up to now. That cultural tradition has more value to me than the architecture itself, although the architecture is indicative of a unique beauty and awe. The series of rooms have their own charm and great prestige that I have not felt anywhere else. It has a wonderful spiritual dimension, as when I first visited the place I was very stunned of the dhikr sessions and their uniqueness.

Al-Zawiyya al-Hillaliyya is a building with a square space. The walls are covered with stunning wood work. There are forty wooden rooms, twenty on the ground level and the rest on the mezzanine level. Each room is one meter in width and one and a half in length, dedicated to one person who would like to practice the Sufis ritual called Hadhra.The person considers this room as his solitude residence, for mysticism and human detachment, to reach self-purity and spiritual communication with the divine self, away from the impurities of life. He stays for forty days and is offered food and drinks regularly in his place of isolation. He does not leave the room unless it is necessary. This practice has been performed in this place since it was established, and it did not even stop during the war period. It resembles the solitude of monks like Saint Simon and others. As the Hadhra is over, and the person had finished his duty that he vowed himself to, he can finally enjoy his spiritual serenity.

Traces of this Sufi tradition can even be recognized in the architecture as for example in the arrangement of rooms and in particular the number of rooms. In Sufism, the number forty is historically considered a sacred number, even before the appearance of the Abrahamic religions. And so al-Zawiyya al-Hillaliyya includes forty rooms in relation to this number.

The rituals of dhikr have rules in which there is a leader who leads the session, assisted by two people chanting poems (Muwashahat) of versatile music scales (maqams), and two others who clap their hands to set the rhythm, either slow or fast, according to the muwashah that is being recited. The sound rises or falls to give the perfect tone for the atmosphere. The rest of the participants either listen or repeat the chanting. It is a wonderful ritual in which even children participate. However, it is a male atmosphere that does not allow women to participate. So women stay outside trying to sneak a peek of what is happening inside to live the moment. This practice here is characterized by its old and important poetry (Muwashahat) accompanied by a high level of music performance.

Being interested in Aleppo’s heritage in general, and Muwashahat (sung poetry) and Qudoud Halabia in particular, I started asking about the places where dhikr sessions are being held. In my enquiry, I have discovered that there are seven places in Aleppo where these dhikhr sessions take place. Al-Zawiyya al-Hillaliyya is among the most famous and oldest ones, so I started frequenting this place.

There, I met with Dr. Jamal al-Din al-Hilali, who studied and practiced medicine as a doctor in Germany. His father was a leader of dhikr sessions. When his father died, Jamal al-Din al-Hilali had to quit his job and life in Germany to take over his father’s place in al-Zawiyya al-Hillaliyya, as the place and position are inherited. I asked him to attend one of the sessions and he replied that women are not allowed to enter. Although there is no Qur’anic text that prevents women from doing so, it is only adhered to the established customs. He could not change the dhikr sessions to be mixed because of their character and history as being male oriented. But he assured me that it is logically possible. Every Friday after the afternoon prayers, the dhikr sessions take place and last for about two hours. This place holds an ancient heritage of Aleppo’s culture.

Beginning of 2019, I returned to Aleppo beginning of 2019, after such a long time being away. I was walking through al- Jalloum area on a Friday afternoon when I heard a rhythmic voice echoing the words of Allah… Allah… Allah. I followed the source of the sound from one alley to another to see myself suddenly in front of al-Zawiyya al-Hillaliyya. I have watched dhikr sessions several times from one of the windows. The sound was what drew me to the place again though I had forgotten where it was exactly. I encourage everyone to attend such ceremonies, as the place is very charming and beyond imagination or description.

Al-Zawiyya al-Hillaliyya has a great historical value because these sessions never stopped despite the war, and continued to take place every Friday! People who take part of these rituals in this place are not considered radicals in any way! It is the unique musical heritage in al-Hillaliyya which drives my passion and those people who have left an artistic trail in it, such as Bakri al-Kurdi, Omar al-Batsh and Sheikh Hassan al-Haffar.

The place has not been affected much during the war. The removal of the graves in the courtyard did not affect the course of weekly dhikr sessions. The place still exists and the wonderful ritual continues. There are fixed dates, and attending is possible. Even if I am just sitting on the steps, it still has a great value to me. I introduced most of my friends to Al-Zawiyya al-Hillaliyya, including a Lebanese friend; a Christian from southern Lebanon. We visited the place together and she wore a veil on her head and sat on the steps with me. She then started hearing the roaring voice of the men inside. Focusing on the voices, she entered a world of spirituality, a state similar to out-of-body experience, of what was happening to the men inside.

You will be impressed by the deep authenticity of this ritual. On Friday, as the men come out of the mosques after the prayer, wearing white djellabas with the smell of rose, musk and amber, and in the presence of the leader, you feel the deep respect and order in the place.

I am optimistic somehow as the war comes to an end. I rejoice on those who restore and do not grieve the destruction. My view of the situation is bright, as I was very pleased to know the place was not demolished and that the rituals are still happening. I see things differently with this elegant Aleppian practice, and the presence of children, boys and adults memorizing Muwashahat (sung poetry) of unknown ancient origins.

As much as we care about the architecture and buildings we have to pay attention to the intangible cultural heritage because we transmit/transfer/exchange it verbally and it is not documented. Aleppo is very stubborn, that is very obvious historically. There are secrets protected underneath the ground. Our heritage will not be lost! I believe in my city and I am certain that this city will not die.

Ruba Rostum

Aleppo Citadel

Nareen

October 2019

I lived in the al-Jazira region (north-east Syria) when I was young. For the summer holidays I used to go to Aleppo in which our visit would always start around the citadel. Not knowing…Read More

Aleppo Citadel

Nareen

October 2019

I lived in the al-Jazira region (north-east Syria) when I was young. For the summer holidays I used to go to Aleppo in which our visit would always start around the citadel. Not knowing why exactly I felt this way, I would always say to my mom that this citadel will be my home in the future. When I was 13 years old, we finally moved to Aleppo. I would often ask my dad to take me to the citadel; s and we would walk around it usually in the evening. One day, one of our relatives visited us and started telling us that one of our ancestors (or our 7th great grandfather) was the one who built the walls of the citadel. He was called “the one with the red beard”. Finally, there was true evidence that I belonged to this place!

My first visit inside the citadel itself was when I was in 10th grade, during a school trip. It was like a dream come true. I left my classmates and began to discover my surrounding stone by stone. I joined the group again in the cafeteria, which is unfortunately completely destroyed now.

I always visit the citadel with my friends. I feel that all my real friends are the ones I have the most memories with in the citadel. My best friend has travelled to the US because of the war, and I always remember our tour together, heading from the Umayyad mosque towards the citadel passing by Beroia restaurant all the way to madrasa al-Shibani. I like walking in Aleppo at night when it is calm, but she used to get scared of the darkness and rainy weather. The smell of rain is so distinctive and the atmosphere is breezy, beautiful and completely quiet as no one is walking around the citadel. It is an absolute pleasure for me. She would ask: “Why do you like Aleppo at night?” I reply: “There is nothing to distract my thoughts around the citadel. The view with the gray clouds and the rain is an outstanding scene”.

However, my most significant memory there is falling in love within the citadel. At work I met someone, who quickly realized how much I liked Aleppo and its citadel and decided to disclose his love to me in a café overlooking the citadel. He knew what a positive energy this place brings me. I remember it was a beautiful night, clear sky, bright stars, wrapped by a cool breeze of early spring. The atmosphere was great and the place was filled with joyful people enjoying the nice weather with music. Every time we used to fight or disagree on something we would always come to the citadel to discuss and take decisions. Our love relationship did not last but it was very special. This citadel is my home. It is part of my identity as I have the most beautiful memories. A part of my personality and character was developed around it.

I have visited the citadel three times after the end of the armed clashes. In the first visit I was in a state of shock. I tried to understand what happened. It was very difficult for me especially since I have certain memories in it. I expected a certain smell that I was familiar with but those smells have disappeared. There was a bad energy around it with a sense of fatigue, soreness and pain, for the people and the place itself. I had a very difficult intense feeling there that I cannot describe. I used to get very happy to stand in front of the ancient stones of the citadel wanting to embrace them if I could, but now this very thing hurts me. On my third visit, I began to understand that part of my memory had been lost. There used to be a big tree next to the citadel’s cafeteria, and when my dream to visit the place for the first time came true I wanted to commemorate the date by carving my friend’s initials and mine lightly and in small on the tree. But during the war, we lost the cafeteria as well as the tree, and up till this moment I search to find their place in vain.

I am willing to do anything that would be of help to the citadel. I tried applying to an excavation work in the citadel, announced by the Directorate of Antiquities, as I had some background experience in the field. I was not lucky enough to be a participant though. It could be that those who were chosen to do the job are more professionally experienced, but still, I try in my own way to preserve and maintain the citadel as much as possible, especially by keeping it clean. It annoys me very much when I see people who are tampering with it and they are not interested in keeping the place clean. So I ask strangers to stop throwing trash on the ground saying: “Isn’t it enough what have already happened to the citadel?!!”

My wish is to raise common awareness about our heritage. Syrians and non-Syrians consider it as part of their international heritage. It is rather an entire human global heritage. Shakespeare has written about the fame of Aleppo being a world trade center on the Silk Road. Aleppo encompasses the whole world and not just us Syrians. I take pictures of all angles of the citadel though I am not a professional photographer, but I keep sending my friends abroad photos of the citadel. They all have this nostalgia because this citadel is part of our identity and ask for more pictures. We will lose the value of our citadel if we do not take care of it. We could start by teaching the people to consider the citadel as their home and so keep it clean as they would in their own houses. I hope there will be complete guided strategies for that, to realize that we are walking on the footsteps of former civilizations that continue to form what we are today.

Nareen

Al-Bahramiyya Mosque

Sami Bahrami

August 2019

I got to know al-Bahramiyya mosque at the age of twenty when my uncle Radwan Bahrami took me there, not knowing at the time that my great grandfather was the one who built it!…Read More

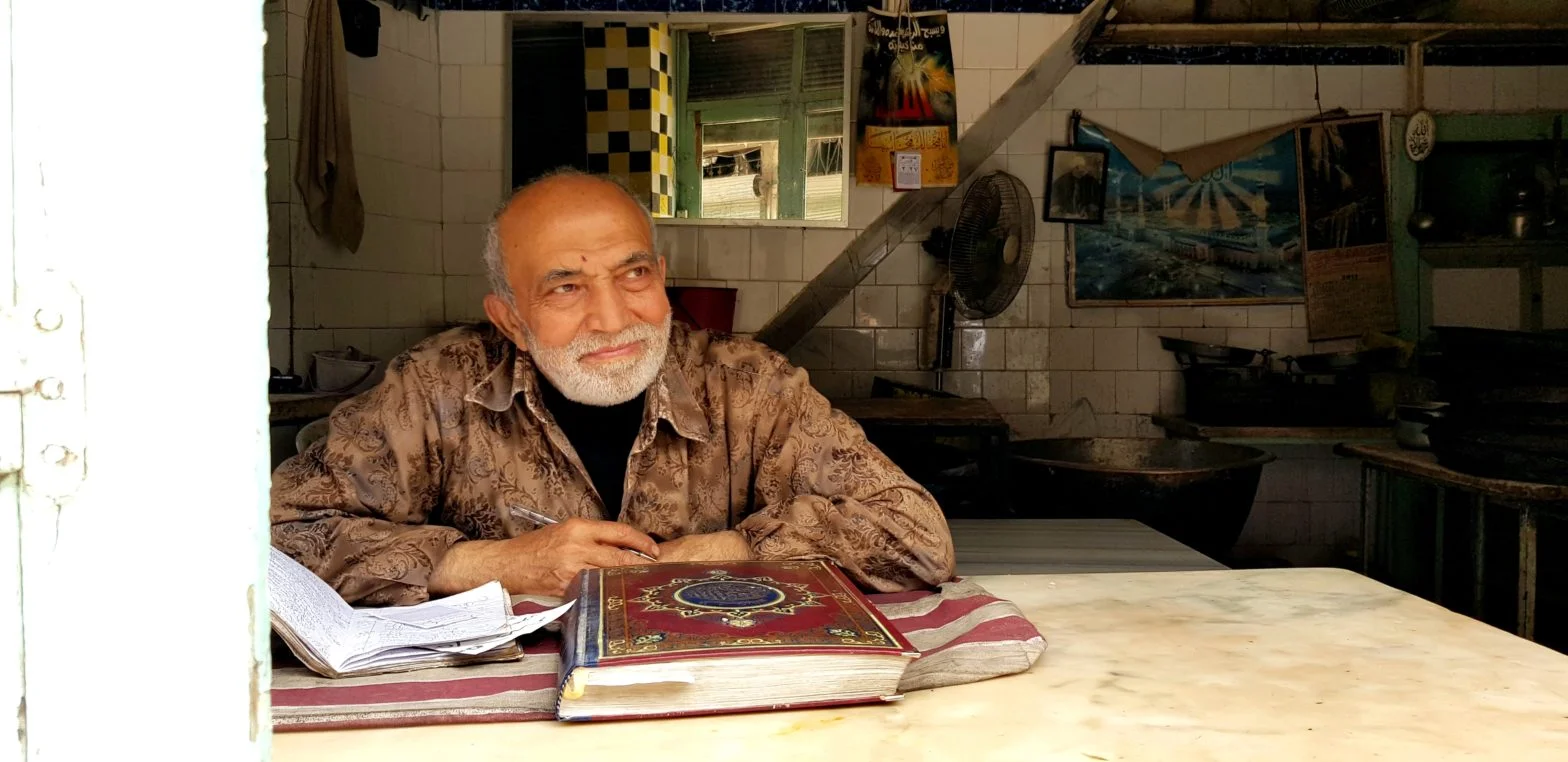

August 2019

I got to know al-Bahramiyya mosque at the age of twenty when my uncle Radwan Bahrami took me there, not knowing at the time that my great grandfather was the one who built it! My relationship started with this place since then and lasted up to seven years. I was periodically visiting the mosque every Friday for prayers. I would go an hour or two before the time of prayer and sit inside a place that dates back between 400 to 500 years old. The smell of cleanliness that exudes from the space is very distinctive as there are three servants working continuously to keep it clean and tidy; the air is fresh and the walls are cool in summer. It has a wonderful uniqueness. The voice of the muezzin Abu Jalal in the Al-Bahramiyya Mosque is original and sincere as he raises the call to prayer. You just have to close your eyes to hear his voice and immerse deeply into your soul, to travel back to the place, with its magical beautiful prayer hall, as you enter a state of complete spirituality.

I remember arriving to the mosque before the prayer time and taking the key from the servant who usually stands at the gate next to the sabil (water fountain) and rinses the floor of the mosque and the souk (market) outside. I open the door of the prayer hall and enter. Next to the window to my right, I see an old man sitting with the Qur’an and a bottle of water reading quietly. I open the locked door with the servant’s key. Despite the fact that the prayer hall is supposed to be empty of worshipers; I would see this old man inside every time. When I asked the servant about him, he answered that this man goes inside the mosque every Friday at the Morning Prayer and keeps reading the Qur’an until the Noon Prayer, and then he goes home; this is his own ritual of prayer.

The mosque’s courtyard is beautiful, but the garden is even more. In the southeastern side, the mausoleum of the mosque builders, Bahram Pasha and his brother Radwan Pasha, is of great beauty and splendor. There are two (closed) entrances to the garden; one is on the eastern side from al-Madras al-Ahmadiyye’s alley where you can see the two shrines, and the other door is located on the western side, opening to the courtyard of the mosque. Before the war, I was unable to visit the tomb of my great-grandfather to recite some Qur’an verses on his soul, because the mosque’s servant never allowed me to enter. Ironically now, because of the war, I was able to enter it for the first time by passing the hills of rubbles of the destroyed shops in the middle of souk Antakiyye and the two khans of Tutun. The destruction was massive and the height of the rubble would reach the length of a human. When we passed through it to reach the door of the mosque it was closed. So we went to the Western side where there are two other doors of the mosque but they were also closed as the neighborhood was full of rubble hills. I saw the wall of the garden torn down so I headed east to the place of the shrine where I saw the tombstones had been completely removed. There are no longer any traces of the graves except the columns surrounding it. At the beginning of 2018, I wanted to rebuild the destroyed garden wall, which is a wall of eight meters long and three meters high. Therefore, I allocated 400,000 Syrian pounds, but the cost study resulted in more than two million Syrian pounds, which I could not afford.

In 1822, a major earthquake struck the city of Aleppo, and the mosque’s dome was completely destroyed. It took forty years to build another one. The construction costs were covered by selling the insulating lead that was covering the old dome, between 1860 and 1864, where four pillars were built bearing the new dome that was smaller in diameter than the old one. Now, after the war and the great damage that affected the prayer hall, the dome and the minaret, I am not optimistic that it will be restored as it was, due to the lack of adequate funding and an apparent expert workforce.

The gallery of the mosque was under the threat of complete collapse due to the damage to one of the external pillars, and its situation was critical if it had remained without repair and restoration. Then Abdo Kno, a donor, supported and repaired it with his individual efforts. The costs of restoring and repairing one pillar were estimated at 700 thousand Syrian pounds, so what would the full cost of the prayer hall be? I visited the mosque more than twenty times after the roads have been accessible again to enter the old city. Every time I visit it I grieve the place as if I see the destruction for the first time. Praying here seems not to be near foreseeable.

I wish for the restoration work to start soon in the mosque, like the restoration in churches and other mosques, and for people to pray in those places again that are memorable to our Aleppian community. I hope to go back to the prayers on Fridays under the mosque’s dome with the same people that we used to pray together before the war.

Sami Bahrami

Khan Al-Wazir

Paul Megarbane’

September 2019

My father had an office and a factory in Khan al-Wazir, where I used to accompany him to as a child. On our daily walk to work, we would always go to Bab al-Faraj post office to…Read More

Khan Al-Wazir

Paul Megarbane’

September 2019

My father had an office and a factory in Khan al-Wazir, where I used to accompany him to as a child. On our daily walk to work, we would always go to Bab al-Faraj post office to open our mailbox, grab the letters and continue the way by tram or walking until we arrived at Khan al-Wazir.

Our factory was relocated several times within the Khan itself. I remember in the beginning, the factory used to be positioned in the northern part; now demolished to widen the street leading from the Umayyad mosque to the citadel. It is told that the former alley used to be so narrow that you could touch both sides of its walls with your hands as you walked. And so, parts of the Khan and a large portion of the opposite building (Matbakh al-Ajami) were demolished in order to facilitate the accessibility to some houses.

After the acquisition of our shops in Khan al-Wazir, we received small government compensation and moved to the khan’s salon; a very good large square hall located just above the entrance. We went up from one of the two parallel stairs, one on each side of the Khan. We continued our work in this salon for about a year and a half before we moved to the western facade where I am still today.

I have many beautiful memories in this Khan visiting the small textile factory, which used to belong to my father and uncle. They had two of the first weaving looms in Aleppo, with a license to practice this profession in the Khan despite the looms’ loud noise. I can still hear the looms’ sound in my head today! How I could tell whether they were working or not even while sitting away in the office.

Our family products were well known as Atlas (Satin weave) Megarbane. In Aleppo, the bride’s apparel usually included garments made of famous Megarbane’s satin, because of its soft and robust quality. In addition to the textile industry we practiced general trade. My grandfather sold goods from satin and cotton fabric, of which a large sum was being exported to Mosul, Iraq.

One of my distant memories is when the demand for our products increased and we were distributing our load of work to some qaysariyyas that have looms in them, to increase our production. There is a special craftsmanship to work on the loom where the worker sits in front of his tools and puts his feet in a hole underneath to lift and lower the strands using his hands to alternate between left and right in order to weave.

Many things have changed in front of the Khan, including the demolition of al-qaysariyya in front of the entrance and the closure of the water well beside the entrance. There was a water tank opening near the door of our factory that was also closed.

Later, my office served as the Swiss consulate. In 2008 & 2009 I organised Syrian-Swiss events and festivals sponsored by Aleppo’s Governorate and the Swiss Embassy in Damascus, such as fashion shows, exhibitions, cultural and artistic gatherings. There is a huge open courtyard in front of the consulate, in which up to 600 people can sit comfortably. A music band from Switzerland held a beautiful concert there once. Colorful lighting during the artistic performances created a very romantic beautiful and serene atmosphere, highlighting the architectural beauty of the arches, columns and open space. Nowadays, the Khan is abandoned due to the war. Its stone and trees no longer give the same impact as before. Unfortunately, it is in a bad condition.

A few days ago, I went to the Khan to make several arrangements but could not bear to stay inside for more than 45 minutes. My heart is sad and in pain. I have witnessed the Khan in its days of glory. Now, all you see is your belongings scattered, thrown to the ground. I do not advise anyone to visit their shattered home. I cannot do anything for the Khan by myself, because I am not the only one who works here. The official interest in the place is not of a priority at the moment due to the immense work required for the old city of Aleppo, which is a very large area. I hope the Khan receives its well-deserved attention from those interested in World Heritage to restore it to its full potential.

Paul Megarbane’

Al-Adiliyya Mosque

Omar Abd Alwahhab Katta

July 2019

I have known al-Adiliyya mosque for more than 45 to 50 years now, as my father used to take me with him since I was 4 – 5 years old. That is why I have a strong and long history…Read More

Al-Adiliyya Mosque

Omar Abd Alwahhab Katta

July 2019

I have known al-Adiliyya mosque for more than 45 to 50 years now, as my father used to take me with him since I was 4 – 5 years old. That is why I have a strong and long history of attachment to this place.

It is a very important place for Muslims in general and the people of Aleppo in particular as it is one of the most ancient historic mosques. It is an early ottoman mosque. It has a historic value of course but also a religious and symbolic value for the people of Aleppo like me, as I used to attend in there sessions of dhikr since I was very young until 10 to 15 years ago when these sessions stopped due to several reasons, among which are the death or move of the people who were responsible.

This of course did not prevent me from going there anyway as the place is full of charm and has a certain specificity to it. Friday prayers used to take place in al-Adiliyya mosque, many people including myself would attend, especially those who knew the mosque and the people responsible for it in the early times. Also on special occassions and religious holidays, especially on Friday, dhikr sessions would take part in the mosque with chanting and sufi ceremonies. Ramadan, Isra and Meraj, mid of Sha’ban. Every Friday there would be something special in this mosque which I assign so many of my memories to from childhood.

Anyone who used to go regularly to the mosque would remember how all your senses would ignite in that place. It has a very specific smell and image to it. There are several Ottoman mosques in Aleppo, but this one has something very unique, whether in its entrance, prayer hall, courtyard, trees, domes, or the niches upstairs where children would sit during special sessions. The memory of the place is so distictive.

The mosque stood for centuries and lived along since my childhood with all its beautiful details. It stands now so strong in my memory. I used to go there regularly to release the stress of daily life, and therefore, it has an incredible value in my heart. The minute I step my foot inside the mosque I feel relieved and all the memories come again. The fragrance of Ahl al-Khier (people of good will) of historic times accompanies you when you enter this place.

I feel really sad and in agony to see the mosque in its current state. It burns my heart to see what had happened to the mosque and Aleppo, of all its historic bits and details. It puts me in tears, and I can not even go and visit it now. If we could just see a real support I am sure many people would just volunteer to help rebuilding it. We can restore a destoryed building but we can not restore how it really used to be, as every stone holds a story of the people of the mosque. I really hope to recover the story of a beautiful time by restoring the stones of the building.

Omar Abd Alwahhab Katta