by Eva Nmeir

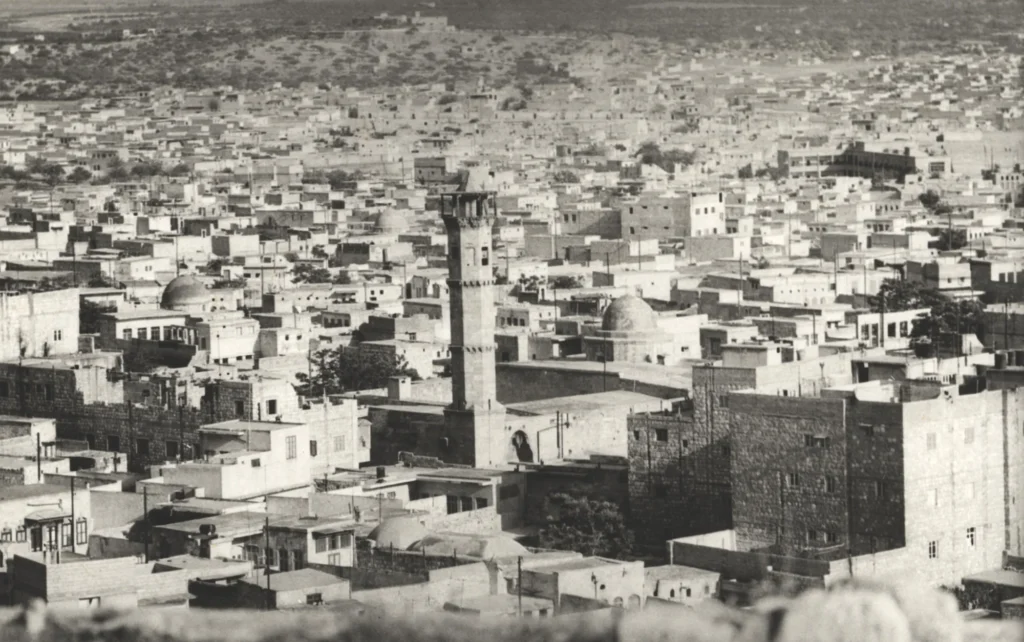

Looking at the walled old city of Aleppo, what particularly catches the eye are the numerous minarets – mosque towers, whose silhouettes stand out against the hill of the mighty Citadel. At one of the Citadel’s uppermost points, another such tower juts into the sky: the 21-metre-high square minaret of the Great Mosque (Upper Maqam Ibrahim) that was renovated by the powerful Ayyubid ruler of Aleppo, az-Zahir Ghazi, in the 7th century AH / 13th century AD (Fig. 3). Whether square, polygonal or round: the minarets in the Old City of Aleppo bear witness to both religious practice and building policy in a unique, historically grown urban cityscape and, not least, to Syria’s diverse architectural landscape.

The tall minarets, in particular, built from the typical local light grey limestone and sometimes elaborately decorated with stone carvings, mark the appearance of the city and set spatial highlights. It is especially these minarets that suffered often substantial damage during the war in Aleppo between 2012 and 2016; rehabilitation work will continue for a long time in some cases. Most important is the square minaret of the Great Umayyad Mosque, the main mosque in the core of the walled old city, which collapsed during fighting in 2013 (Fig. 1, 2). Over 900 years old, it was one of the most ancient minarets and Aleppo’s most outstanding landmark, along with the Citadel. Besides wars and fires, earthquakes repeatedly damaged minarets in the course of the city’s history, making restoration or renewal necessary.

The extraordinary stylistic diversity of the historical minarets plays a crucial role for the distinctive character of the Old City of Aleppo (Fig. 3–5). From the late 5th century AH / 11th century AD, when during the reign of the Seljuk sultans the minaret of the Umayyad Mosque was built, through the times of the Zengids and Ayyubids up to the Mamluk and Ottoman periods, a variety of building traditions and ornamental influences were at work. In western Syria, the older minarets usually have a square cross-section; the very first were likely built on the model of existing church towers.

The 45-metre-high minaret on the north-western courtyard corner of the Great Umayyad Mosque, built on a square ground plan with a side length of 4.95 metres, dated from the AH 480s / AD 1090s (Fig. 6, 7). This minaret, which presumably replaced a previous structure at the time, was to remain for centuries the tallest in all of Aleppo. Despite being extensively restored a few years ago, it was slightly leaning before its collapse. A spiral staircase with 140 steps led up to the balcony-like gallery for the muezzin, the prayer caller. This was crowned by a small domed minaret top. Especially in the two sections below the gallery, the four-zoned minaret shaft was accentuated by circumferential moulded bands indicating arch openings (blind arcades). Thus, the architectural decoration reflected a local style that reaches back as far as pre-Islamic Late Antiquity. Arabic inscriptions mentioned, among others, the patron of the building, Ibn al-Khashshab, who was the city’s chief judge (qadi) and a member of an influential local family.

It was in the Mamluk period that several additional Friday mosques with impressive minarets were built. The war-damaged minaret of the Jamiʿ Altunbugha to the south-east of the Citadel (founded in 718 AH / 1318-19 AD by the governor who gave it his name, Fig. 8) is subdivided into three sections by muqarnas (honeycomb work) friezes, with a roofed gallery forming the top. The characteristic feature is now no longer a square but an octagonal shaft cross-section, whereby the square base remains. The octagonal Ayyubid brick minaret of Balis-Maskana (early 7th century AH / 13th century AD, Fig. 9), located on the edge of the Euphrates region – the Syrian Jazira (north-western Mesopotamia) – halfway between Aleppo and ar-Raqqa in the east, is an important forerunner of the new development in Aleppo. This is supposedly associated to a considerable extent with the architectural development in the Egyptian city of Cairo, the capital of the Mamluk Empire.

The significant Jamiʿ al-Utrush (founded in 801 AH / 1399 AD) at the southern foot of the Citadel, also endowed by a Mamluk governor of Aleppo, features a minaret with two galleries, which is an exception within the old city (Fig. 10, 11). This minaret, extensively repaired during the last century and damaged by the war as well, has two shaft sections of different diameters standing one above the other. Here, the possibilities of Cairo’s multipart Mamluk minaret architecture find their resonance.

Besides these two austere Aleppine minarets, there are minarets of the same period that are much more ornate, with blind arches formed from moulded bands and muqarnas cornices as recurring elements (Fig. 12). Among these, the minaret of the Friday mosque Jamiʿ al-Mihmandar (early or mid 8th century AH / 14th century AD) north of the Citadel was particularly striking (Fig. 13). The round main shaft was completely covered with long ribs, straight in the lower and zig-zagging in the upper zone. This outstanding minaret underwent extensive dismantling and rebuilding around the middle of the 20th century due to a slight lean. It was severely damaged during the war and collapsed at the end of 2016.

A second exceptional minaret is the corner minaret of Jamiʿ ar-Rumi or, after the founder’s name, Jamiʿ Mankalibugha (finished 769 AH / 1367 AD) south of the Citadel (Fig. 14, 15). It has a tall, slender, round main shaft that tapers slightly towards the top and is divided into four zones; it was severely damaged by the war in the upper section. The round cross-section, unusual for Aleppo at the time, is reminiscent of buildings further east in northern Syria, on the Euphrates in the Jazira region and the city of ar-Raqqa (Fig. 16). There, the brick minarets in turn refer to the minaret-building tradition in the east – in Iraq and Iran. In addition, the round building shape was included in the Seljuk-Turkish stone building tradition of Anatolia, which borders to the north. Decorative elements associated with this are, for example, rib motifs.

At the end of the sequence of traditional historical minaret forms, there are the round-facetted minarets with a pointed cone roof as well as a balcony projecting broadly above a muqarnas cornice typical of the Ottoman-Turkish architectural style. They found their introduction in Aleppo with the minaret of the madrasa-mosque Jamiʿ al-Khusrawiyya (completed 953 AH / 1546-47 AD) in the centre of the large endowment complex of the Ottoman provincial governor Khusraw Pasha (Fig. 17, 18). Contemporaries perceived the towering pencil-shaped minarets quite consciously as Ottoman buildings and also as symbols of Ottoman rule. Today, the first of these impressive minarets is gone – the Khusrawiyya Mosque was completely blown up in 2014.

At first sight, the historic minarets of Aleppo’s walled old city stand out clearly against modern minarets built from concrete, steel and glass, for example in the neighbouring western new town. On closer inspection, however, it is to a large extent a traditional repertoire of architectural forms and decorative motifs to which the very tall and much more prominent minarets of mosques refer, such as Jamiʿ ar-Rahman, the largest mosque northwest of the old city with a total of three square double minarets, or the northerly Jamiʿ at-Tawhid with its four slender, hybrid-shaped corner minarets (Fig. 19 and 20, both from the last quarter of the 20th century).

Featured image: The Old City of Aleppo – view from the west onto the Citadel, in the foreground is the minaret of the Jamiʿ Sayf ad-Dawla (2001) | Peter Heiske (CC-BY-NC-ND)

Published by Eva Nmeir: Art historian with special reference to Syria. She worked for the Syrian Heritage Archive Project and its co-projects on the World Heritage sites “Ancient City of Aleppo” and “Ancient Villages of Northern Syria”, among others.