by Prof. Hassan Abbas

The Levant is the birthplace of the three main monotheistic religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. All of these religions either emerged in the region or developed and expanded there, split into sects, and spread to the rest of the world.

Although the region has seen conflicts between followers of the three religions, their cultures still coexist as distinct components of Syrian culture.

Explore music in Syria through the lens of religions

Christian Music

Christianity came out of what is today Palestine and spread across the world. Syria was the land in which the early sites of the new religion were established. There is still a strong Christian presence in Syria. Folk tales and stories from the early days of Christian history tell about the first saints and their meetings in caves. Monasteries and churches of all ages continue to demonstrate the depth of Christian presence in the region. There are eleven different churches in Syria, from which three types of church music can be distinguished: Syriac, Byzantine and Armenian.

| Syriac Music |

Source: anonymus, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Syriac Orthodox Church originated in Edessa (present day Urfa). Adherents would recite simple hymns taken from Hebrew Jewish heritage. In the first three centuries of the first millennium AD, some of the church fathers, like the philosopher and poet Bardaisan of Edessa (154-222 AD) produced new texts for prayers and hymns with local melodies.

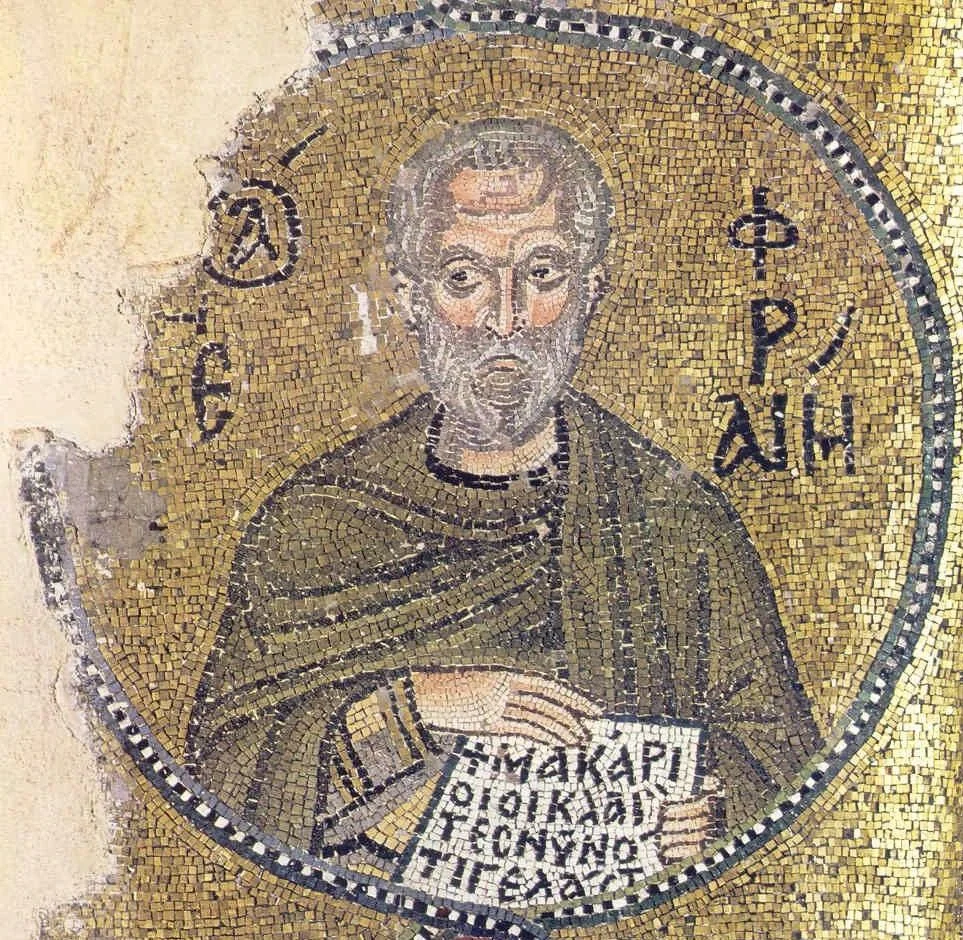

Saint Ephrem the Syrian (306-373 AD) believed that Bardaisan’s melodies distracted young people from their religious duties. He thus produced new serious hymns with endearing, beautiful melodies. He created a girls’ choir in Edessa that performed during prayers and religious services. Through hymns that still exist till today, he was able to attract the youth and bring most of them back to the church.

The Syriac Orthodox Church does not allow the use of musical instruments and musical accompaniment to services and hymns inside the church. This position is shared by all the Eastern Orthodox Churches.

Syriac Christian religious music can also be considered a form of ethnic music as it represents the music of the Aramean people who lived in the Eastern Mediterranean region and maintained their presence as a people and a language from 1500 BC until the beginning of the tenth century AD (there are still three villages near Damascus that speak Aramaic).

| Byzantine Music |

After the first four centuries, differences in church music arose along with the progress and differentiations between of the churches. The Byzantine Church used the Syriac tonal system after making numerous elaborations and changes to it.

In the sixth century, the Syriac Saint Severus of Antioch (465/459-538 AD), the Patriarch of Antioch, set out a musical system based on eight modes (ألحان) (alhan). He used the eastern maqams (melodic modes) that are known in contemporary language as Bayati, Rast, Saba, Hijaz, and so on. This system provided the foundations of Byzantine Church music. Pope Gregory used it to produce the chanting system known as Ambrosian and later Gregorian chant, which was used by the Roman Catholic Church.

In the nineteenth century, due to major developments in Byzantine Church music, especially as a result of the influence of Arab and Persian music, a reformist movement emerged led by three churchmen who set out the bases of Byzantine music, called the “Three Teachers” system of notation, which is still in use to this day.

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, most churches in Syria held prayer services in Greek as they followed the Greek Orthodox-majority Antioch Patriarchate and during mass, they would use the Syriac language for the words of consecration. Chanting in Arabic began with Yusuf ad-Domani, who came from Constantinople to teach Byzantine Church music. His student Metri al-Murr (1880-1969 AD) provided the notation for this new tradition.

Byzantian hymn Rejoice, O Queen sung by Juman Abdullah and Elias Bouras.

Ison

The main feature of Byzantine chant is ”Ison“, a chant sung at a tonal level performed by a small number of the choir in one extended breath from the start to the end of the chant. If there is a change of jins, the “Ison” is sung at the tone of the new jins, and so on.

| Armenian Music |

The Kingdom of Armenia embraced Christianity early on and was the first Christian state in history. Like other nations, the Armenians sung the Psalms in their church rituals before they started to compose their own chants.

At the beginning of the fifth century, a group of scholars, the most famous being Saint Mesrop Mashtots (361-440 AD), with the assistance of the Syriac Church in the Syrian city of the Edessa (Urfa in present-day Turkey), invented the letters of the Armenian language in 406 AD. In that same year, the Holy Bible was translated into Armenian. It was the impetus to complete the notation of liturgical texts with Armenian melodies.

At the end of the sixteenth century, the scoring of Armenian music stopped. This continued until the twentieth century, which led to the loss of a great part of Armenian musical heritage. Safeguarding Armenian melodies is largely credited to the priest Komitas (Soghomon Soghomonian, 1869-1935 AD) who introduced polyphony to Armenian music at the end of the nineteenth century and collected Armenian melodies, eventually preventing a final loss. Komitas is considered the founder of modern classical Armenian music. Much of his work focused on the collection and notation of folk melodies and placing emphasis on the ethnic qualities of Armenian music.

After the arrival of Armenians in Syria in the mid-1920s, Armenian churches, particularly Orthodox churches, opened in larger Syrian cities. Armenian religious music thus became an integral part of traditional religious music in Syria.

Jewish Music

Jews were an integral and inherent part of the Syrian community up until the second half of the twentieth century when they started to leave the country gradually. Very few Jews remain today. They have contributed to all aspects of Syrian cultural life and their influence continues to this day.

The types of Syrian Jewish religious music did not differ from others used by Jews in their prayers. There is also no secular music that is specific to them. However, a number of Jewish musicians became famous in the first half of the twentieth century, particularly in Syria’s main musical city, Aleppo.

They include the Oud player Nasim Murad, the singer Esther Al-Hakim, known as Tira, and the singer known as the Fairouz (Mamish) of Aleppo. Esther al-Hakim was a famous Jewish singer. She was also part of the theatre group established by the father of Damascene theatre Abu-Khalil al-Kabbani. Ottoman documents report, that the group travelled to Chicago in 1839 to perform. Her nickname Tira (bird) is believed to have inspired the famous song Ya Tira Tiri Ya Hamama, composed by al-Kabbani. Fairouz Mamish, also known as Fairouz from Aleppo, was a Jewish singer from Aleppo (1895 – 1955). She recorded several songs with the composer and pianist Antoine Zabita (1914–1979), the violinist Sami al-Shawa (1885–1965) and the Jewish oud player Shehadeh Saadeh.

| Famous Jewish singers |

Esther al-Hakim

Sabah Fakhri performing the Song “Ya Tira Tiri Ya Hamama”

Fairouz of Aleppo

The famous song Ya Mayila ‘alghusson performed by Fairouz of Aleppo in 1926. Source is the personal archive of Alaa al-Sayed

Islamic Music

Islam’s position on music is ambiguous and contradictory. There are two opinions on the subject: one opinion states that Islam has prohibited it while the other states that it has allowed it. The fact is that the Qur’an, the supreme constitution for Muslims, is completely neutral on the matter. It does not contain any reference authorising, legislating or promoting music, but at the same time, there is no reference that prohibits, rejects or implies aversion to it. Islamic law is full of conflicting attitudes and legal opinions (Fatwa) on the subject. At the same time, Islamic history is full of stories of enjoyment of music, song and dance, with music being used by all sections of the Islamic community, at the assemblies of the religious and political authorities, as well as its prevalent use in the social life of the Muslim community.

Music became an activity that was encouraged and overseen by the state in the time of the first Nahda (Arab renaissance) led by Muhammad Ali Pasha (1760-1849 AD), the ruler of Egypt. Military musical bands were created and schools were established to teach music. Since then, music became a factor of modernisation in Egypt and Syria. It became a part of everyday life for the whole community, away from the authority of religion and its sheikhs. Islam has invested in music and its spiritual and emotional effect. It has adapted music to its teachings so to become inherent to many religious practices and rituals, many of which are official rituals unique to Islam. The main Islamic musical forms are:

The collective call to prayer in the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. Praise and prayers for the Prophet Mohammad are performed individually and can be heard at minutes 03:25, 04:51 and 05:25 of the video.

Adhan

The Adhan is the call to prayer sung by a muezzin with a beautiful voice. This follows the example set by the Prophet Muhammad who chose the first muezzin in Islam, Bilal, for his beautiful voice. The Adhan consists of a set number of sentences. In some sects and denominations in certain countries additions can be found.

Musically, it is not acceptable for it to be accompanied by a musical instrument. Most of the time, it has a fixed melody (Hijaz or Rast maqam). Some sheikhs, who have a unique musical talent, however, do not hesitate to perform the adhan in their own unique style, leaving their musical mark on a holy religious act. In some towns, in Syria and elsewhere, the muezzins recite lines of verse before starting the adhan, called reminders or recitations, especially before the adhan for the dawn (fajr) prayer on ordinary days, the night (isha’) prayer on Thursday evening and the midday (zuhr) prayer on Friday. Some sheikhs sometimes perform the adhan as a collective choir, as at the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus.

Dhikr

Dhikr is a form of worship in which the adherent, individually or as a group, remembers God. Dhikr gatherings are social religious meetings that bring people together in mosques, Sufi lodges (Zawiyya) or homes. The meeting is held at set times unrelated to religious occasions. The main festivities, however, take place on religious occasions, particularly mawlid, when several hundred people may take part in the zikr.

The dhikr starts with recitations from the Qur’an and then takes different courses depending on the style of the reciter (munshid). The dhikr is made up of parts called “segments” (al-Fusul/al-Fasl). Each section has its own words, chants and movements. There is no set arrangement for the sections. The munshid incorporates into the section muwashshahat, qudud and mawwal that change each time, according to his vocal ability, repertoire or even his mood.

Some Sufi orders have special practices that accompany the dhikr. In the Rifaʿi order (tariqa), for example, some participants in the dhikr perform a body piercing ritual, in which metal skewers of varying lengths are inserted into specific areas of their bodies. Most often, these are the cheeks, tongue, loins and stomach, without any blood flowing. This is considered one of the miracles of their order.

Mevlevi Order

The Mevlevi order performs a “whirling” ritual as part of its dhikr, whose secrets, it is said, were received by the founder of the order, Mawlana Jalal ad-Din ar-Rumi from Shams ad-Din at-Tabrizi in Konya in 1244 AD. The whirling ritual is performed by a group of participants called dervishes. But not all of the Dervishes are allowed to perform this ritual, as lengthy experience and training is required which not all members of the order have.

| Islamic Festivals |

There are many festivals observed in all places Muslims live in around the world, during which adherents chant simple phrases, supplications or prayers collectively with almost fixed melodies. Most of these festivals are restricted to men, particularly when they take place in public spaces, such as mosques. Some festivals, such as the prophet’s birthday (Mawlid), are also all-female. The main festivals are:

Takbirat al-Eid: chanting (Allah Akbar multiple times) on Eid al-Fitr, at the end of Ramadan, and Eid al-Adha, after the Hajj rituals are completed.

Mawlid an-Nabi: The birthday of the Prophet Muhammad is in the month of Rabi ʿ al-Awwal, the third month of the lunar calendar. This is the main religious festival for Sunni Muslims. The Mawlid celebration includes passages recited from the Qur’an by a single reciter, or collectively by the crowd gathered in the mosque.

| Special Islamic festivals |

Special festivals are those that are not considered common to all Muslims but are celebrated by a group or sect. Syria is home to numerous sects and denominations that each practice their own rituals. These are accompanied by a special type of music or even involve popular musical styles, by changing words in a specific way to correspond to their specific ideas or beliefs. Women’s participation in these special festivals depends on the particular view each sect or denomination holds of women and their role in society. The festivals include:

The “fourth” festival (Eid ar-Rabiʿ): the fourth of April, according to the Julian calendar, or the seventeenth April, according to the Gregorian calendar, is celebrated by the Alawites today. In ancient civilizations it used to mark the New Year or the spring celebration.

The “Joy in God” festival (Eid al-Faraḥ bi-Allah): This festival is held on 25 August and is the only festival of the Murshidi sect, commemorating the beginning of the Murshidi School by its spiritual leader Mujib bin Salman al-Murshid on 25 August 1951 AD. The festival’s rituals take place in marquees set up especially for this occasion, called squares.

The “Thursday of Sheikhs” festival (Yawm Khamis al-Mashayyikh): The last Thursday in April is dedicated to Sufi sheikhs who show their miracles. The festival involves a parade by followers of the Sufi brotherhood, accompanied by musicians and flag bearers. After visiting the graves of the masters of the brotherhood, the group goes to a square where a religious dance is held and the sheikhs show their miracles to the crowds of spectators.

The “Ashura” festival (Ihtifalat ʿAshura ͗): held on the tenth of the month Muharram, the first month of the Islamic hijri calendar, Ashura is of enormous importance to the Shi’ite sect. It commemorates the events at Karbala, when the third imam, Hussain bin Ali, was martyred. Every year, a large group of followers of the Shiite sect hold ceremonies and rituals to commemorate this event and to engrain them in the collective memory of their adherents. The story is told and chants are performed by experienced and specialist sheikhs. The songs that accompany the festival can be performed by a ‘civilian’ reciter known as Raddud.

Shared festivals amongst religions

In Syria, there are many festivals whose ceremonies still clearly maintain and involve a celebration of nature by the agricultural community. Festivals at the end of March and the beginning of April, whose origins lie in the ancient new year and the return of spring are examples of this. Some of these festivals refers to the blooming of flowers and have different names; for example, “Floral Thursday” (Khamis az-Zuhur), this equals Holy Thursday in English) for Christian denominations is “Plants/Floral Thursday” for the various groups of the Sunni denomination and the “Floral Festival” (the name given to the “fourth” festival”) for the Alawites. Some refer to the start of the wheat sowing season as Saint Barbara’s Day, which is 7 December for Western Christian denominations and 14 December for Eastern Christian denominations. St Barbara’s Day is also celebrated by the Alawites.

The celebration of these festivals in areas with sectarian diversity involves children of all the religious groups taking part in singing the same chants as they run in the streets, going from house to house to collect gifts from residents.

Continue with Music & Community

Feature Image: Mosaic of Female musicians found in a Byzantine villa in Maryamin, Syria (late 4th century AD – early 6th century AD) – Source: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Prof. Hassan Abbas was the Program Director of “Culture as Resistance” at the Asfari Institute for Civil Society and Citizenship, American University of Beirut and a leading scholar and expert on Syrian culture, and Syrian traditional music in particular. In his book ‘Traditional music in Syria’, Dr. Hassan Abbas distilled his knowledge of years of extensive research on the musical tradition of Syria. His book is available in Arabic here.

After having battled a long-term illness, Prof. Abbas died in March 2021. The team of the Interactive Heritage Map of Syria project is forever thankful for having had the chance and privilege to work with Prof. Abbas and learn from his brilliant mind.