by Dr. Anke Scharrahs

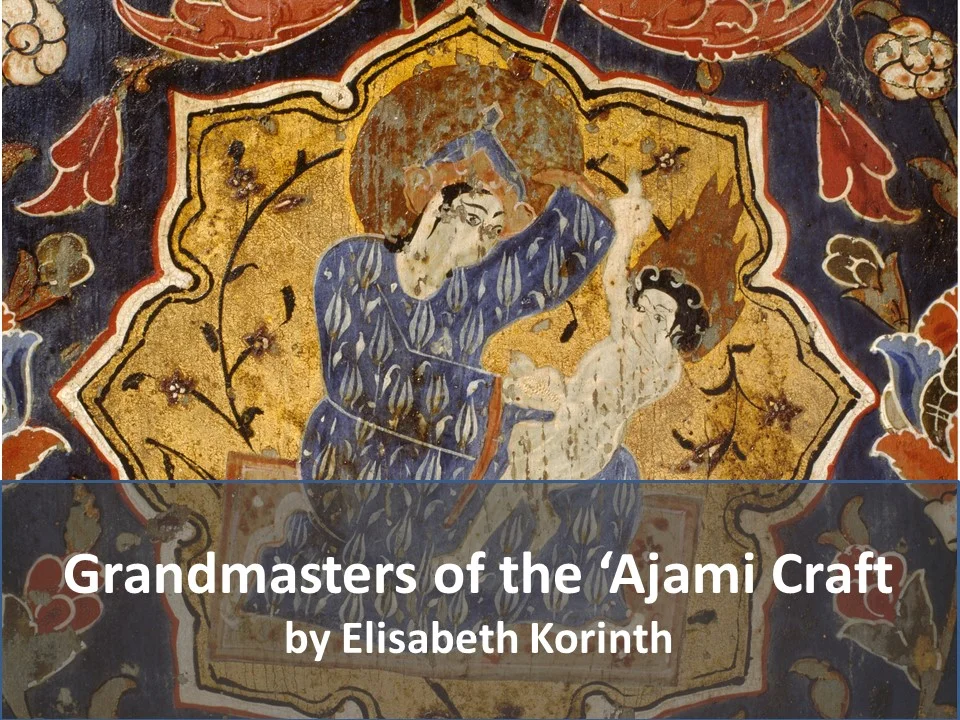

‘ajami panels and ceilings were crucial elements of elaborate interior decoration in 16th to 19th centuries private homes in Syrian cities. They interact finely balanced with gorgeous stone mosaics, softly coloured paste work, gilded and painted masonry, splendid tiles, and exquisite textiles. Decorative techniques and the materials used evolved during time as well as the motifs did. The pattern, flower vases and small landscape paintings show influences from India to France and from Iran to Turkey among other origins. The decorations reflect both, the specific taste of each single owner-builder and the sophisticated skills of the artisan workshops. The materials used were either sourced or produced locally or originated from far regions as for example rare pigments or dyes. Artisans had to juggle the ambitious task of creating spectacular vibrant surface decorations with expensive materials but being still affordable for the clients. Some of the lost secrets how the artisans achieved special effects and extraordinarily brilliant colours could be revealed with modern analytical techniques and microscopic examinations. Among the rediscovered painting materials is crushed cobalt glass (called smalt), carmine (dark red made from lice) and aloe (colorant for orange lacquer).

In 18th century Damascus, there were no shops yet selling tins or tubes with readily made paint as we are used to today. One has to imagine that all materials for the production of the ʿajami panels had to be made by hand in the workshops, for example the preparation of the paints by crushing minerals, handling plant dyes or certain toxic materials. One of the most fascinating materials was a sparkling orange yellow pigment that was widely used because of its incomparably intense golden-like colour and its special condition of double-breaking the light in its crystal structure. As fascinating as this material is for artists, as dangerous it is because of its highly toxic nature consisting of pure arsenic. The bright blue paint found in many rooms under brown varnish layers was made by tinting glass during heating with expensive cobalt oxide and crushing the glass to powder afterwards. The old masters also had to know which liquid was the appropriate one to be mixed with the various pigments to achieve bright colours. For example, the blue glass powder appears black when being used in oil or resin, but results in a bright blue when used with egg white or glue. Brilliant red colour was achieved when painting a bright orange under layer first that was then covered with a thin layer of expensive vermilion red. The thin red layer alone would be quite pale.

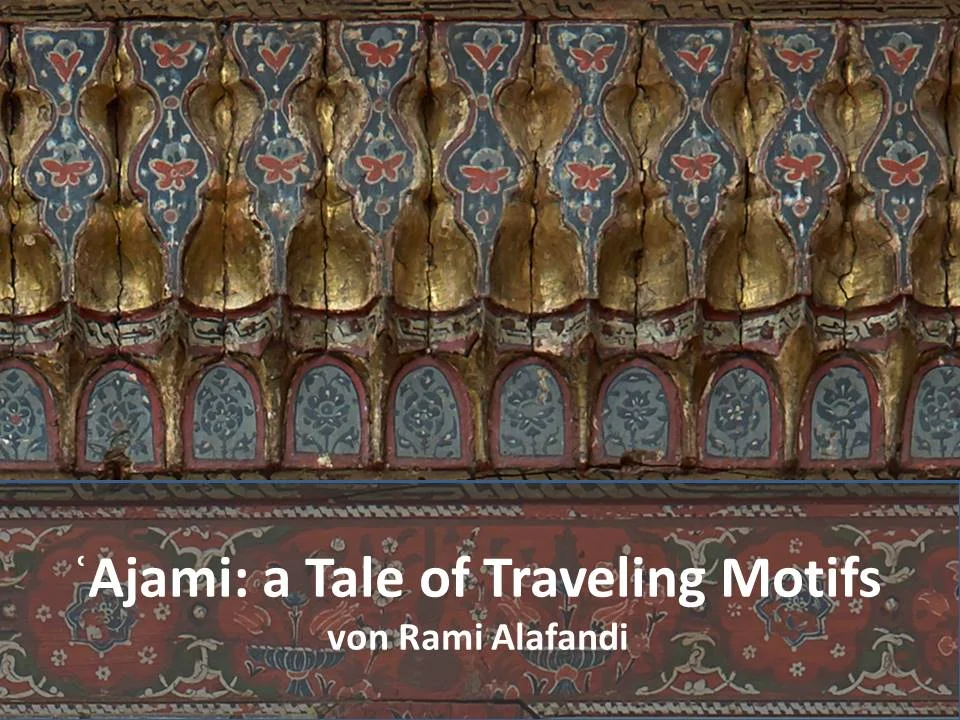

The special effect of the ʿajami reliefs was created by using a thick-flowing paste only made from unburnt gypsum and glue. This mixture had to be applied quickly to the wood because it needs a temperature of approximately 60 °C to be liquid enough for creating the raised pattern. In lower temperature the paste would congeal too quickly before the artist could complete his motifs. The artisans had to be well experienced and skilled with a quick and steady hand and had to know the motifs by heart in order to achieve the complicated ornaments using such tricky material.

The artisans did not only use various paints and tinted lacquers; they were also masters in the application of metal leaf and foil. Sensitive razor-thin gold leaf was used with special brushes and tools as well as the thicker copper leaf and tin foil. These metals were applied to the raised ornaments creating a special reflection of light. Some metals were polished to high gloss; some were applied on a rough surface in order to achieve a matte surface – similar to nowadays metallic paint. All these various efforts were made to create specific surface textures and contrasts as for example between polished gold leaf and matte sparkling azur blue, silver-coloured tinfoil and glossy dark red glowing lacquer, satiny pink and light blue, glossy copper leaf and silky orange paint, matte violet and green lacquer.

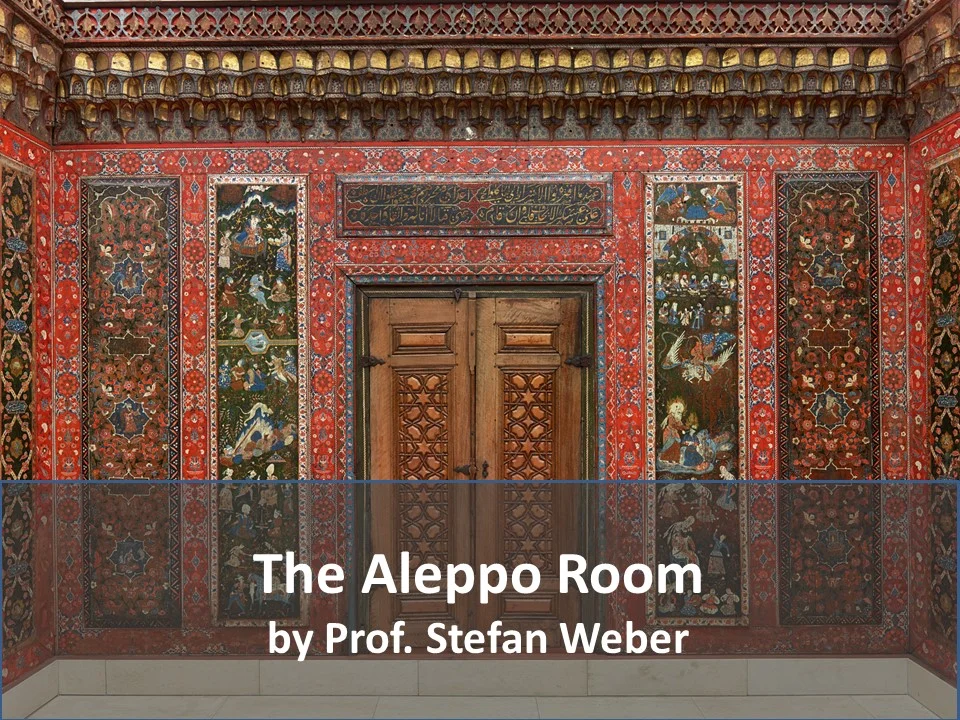

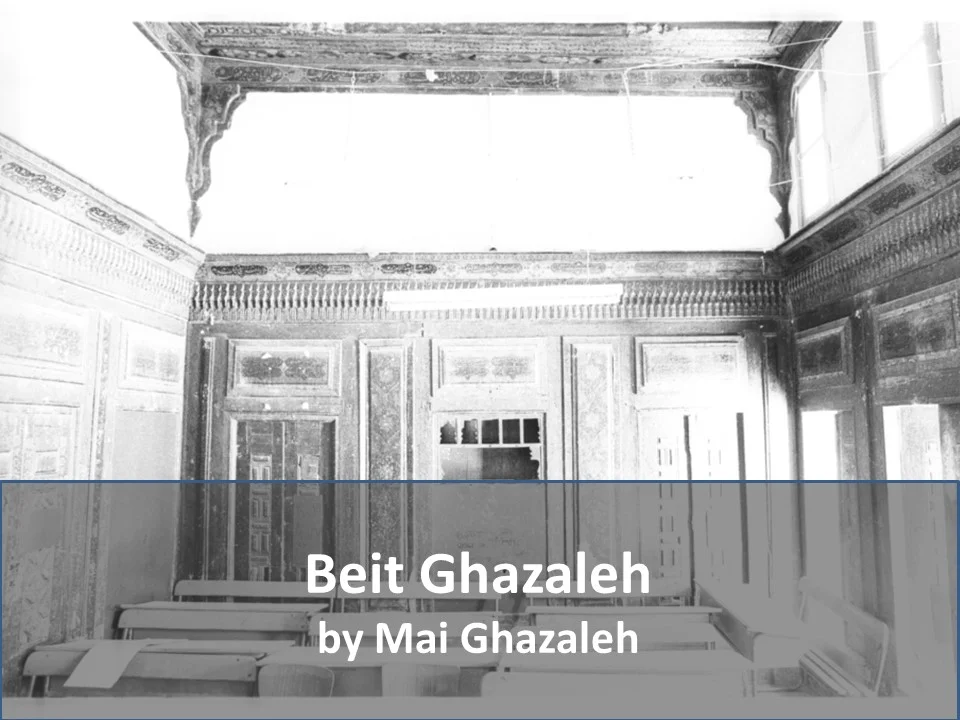

The entirety of the elaborately composed surface decoration, with its veils and layers of shimmering pattern and colour, produces the uniquely glorious atmosphere of Damascene residences. The patterns and colours of the painted wooden decoration are related to those of the stone mosaics; for example, motifs similar to those in the ceiling patterns may appear again in the floor pavement. The finely honed black marble forming the background of many mosaic panels is perfectly in concert with the vivid black lines of the painted pattern on the ʿajami panels. Silver and gold threads in the silk fabrics and embroideries call out to the metal-leafed surface details of the walls and ceilings, and the colourful carpets and ornamental cushions play a symphony with the painted wood panels all around. The mother-of-pearl inlays and the mirrors shimmer in silvery light, creating a sparkling effect when moving inside the room, playing the same notes as the dazzling water of the fountain spouts. This change and play of light during the day is one of the most fascinating discoveries in these rooms. It means they were made to delight visitors again and again throughout a long visit in the house, designed to slowly change and shift their expression and ambiance over time. The well-balanced nature of the bright colours, ornaments and architectural elements are testament to the high quality of the work and the skill of the artists, which leaves a deep impression on every visitor.

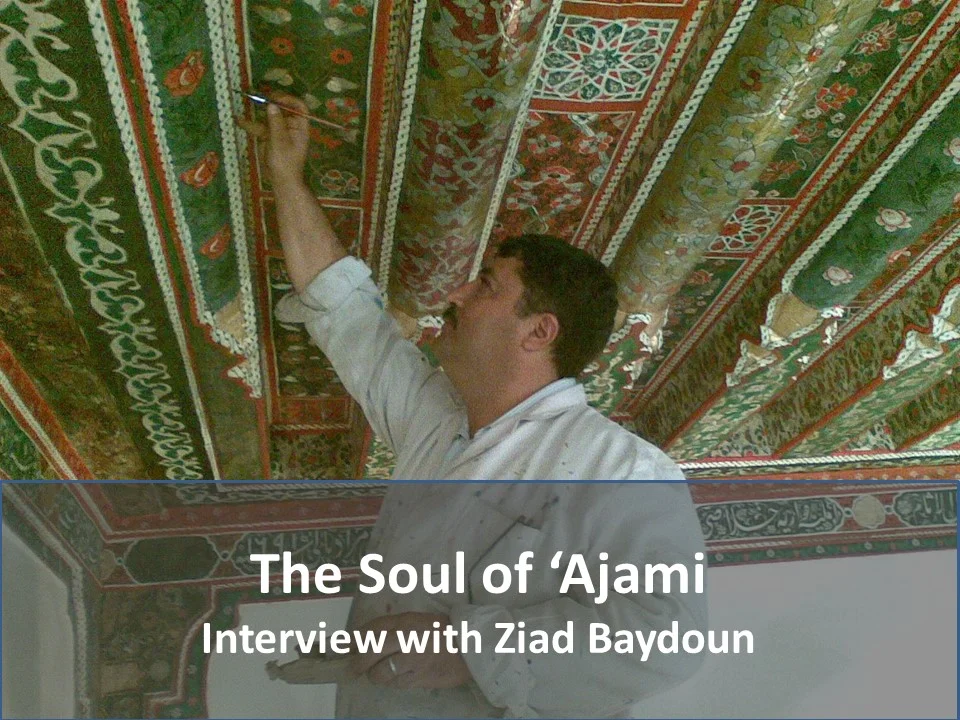

The knowledge about the materials, the painting techniques, and the motifs was handed down in the family workshops from one generation to another. But in the 1850s a drastic change happened and many of these secrets got lost because the production of such ʿajami decorations declined dramatically. There were two main reasons for this: firstly, dramatic changes in the economic situation of the people after the opening of the Ottoman Empire to cheap products from industrial Europe; and secondly because the taste of the people and the style of home décor changed. The ʿajami workshops did not find clients anymore because people favoured Baroque-style ceilings painted in European manner on canvas or large-scale landscape paintings on the walls instead of wooden panels. Because of that many of the secrets are lost for ever. Only a few can be detected with scientific analyses and research.