by Eva Nmeir

The main mosques of Damascus and Aleppo each form the extensive, bustling core of the densely built historical old town of these largest and most tradition-rich Syrian cities. Both are known as “al-Jamiʿ al-Umawi al-Kabir” – “Great Umayyad Friday Mosque”. They were founded about 1300 years ago, when the Umayyad Caliphate (41–132 AH / 661–750 AD) was at the height of its power and the first major Arab-Muslim empire was ruled from Syria with Damascus as its capital. Today, they still rank among the most important places of worship in the world.

The two mosques were built at the end of the 1st century AH / beginning of the 8th century AD in the form of a courtyard mosque with a horizontal rectangular ground plan and a deep prayer hall (haram) along the southern side facing Mecca; the original existence of the narrower hallways (riwaq) surrounding the courtyard (sahn) is attested for Damascus (Fig. 1, 2). In fact, the original buildings each saw their own development – destruction by war, fire or earthquake was frequent, and their renovation or repair is, to this day, one of the most important building tasks of supreme rulers. While the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus was not affected by the recent acts of war in Syria, Aleppo’s Umayyad Mosque was severely damaged.

The architectural and decorative styles reflect Syria’s changing, multi-layered history in a unique way. Moreover, they bear witness to the different geographical and political conditions to which the cities of Damascus and Aleppo, in the centre and the north of the country respectively, were subjected. Taking a closer look at these extraordinary buildings reveals some fundamental similarities and differences.

The Great Umayyad Mosque of Damascus

The Great Umayyad Mosque of Damascus (Fig. 1, 3, 4) represents the oldest surviving mosque building. Significant basic features of the architecture and decorative design were maintained in the old building fabric, though only to a limited extent. This great mosque was commissioned by Caliph al-Walid ibn ʿAbd al-Malik and completed in 96 AH / 715 AD. The structure made use of the enclosing wall of the ancient Roman Temple of Jupiter, a site under which lie the remains of the Aramaic Temple of Hadad. On the same site, the Late Antique cathedral church dedicated to Saint John the Baptist was dismantled and its materials further utilized. It is believed that the head of the saint or, respectively, prophet (Yuhanna al-Maʿmadan, in the Koran Yahya) is kept in the mosque’s shrine. It is an important pilgrimage site for both Muslims and Christians (Fig. 5).

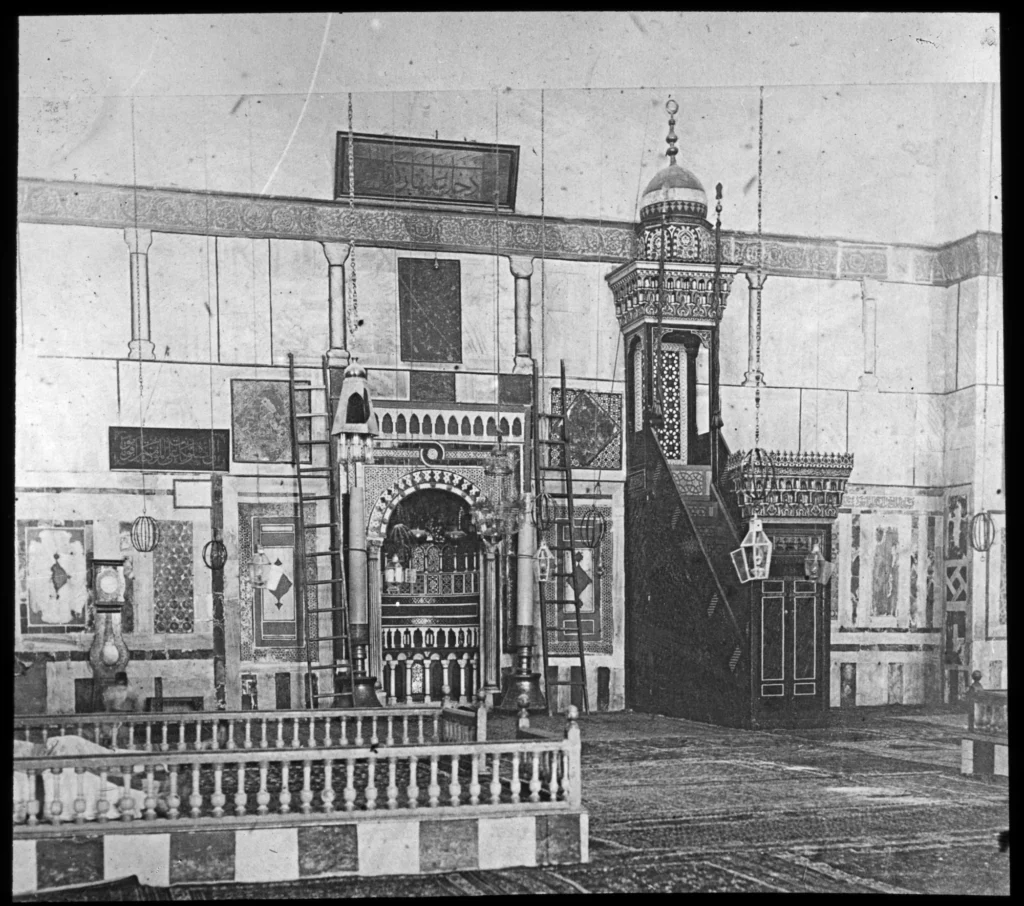

The Umayyad Mosque, measuring 100 x 157.5 m in length and width, provides a glimpse into the early days of monumental mosque architecture. In Syria, this developed in contact with the established Late Antique-Early Byzantine building tradition. Reminiscent of the basilica type of church, there are rows of high, two-storey arcades that run parallel to the long side of the wide and light prayer hall, forming three naves and supporting the roof; each of them rests on 20 tall, reused columns with Corinthian capitals (Fig. 4). However, the alignment of the mosque is different: running transversely to the long side, a broad, high structure (transept) with a dome accentuates the space in front of a central prayer niche (mihrab) in the southern qibla wall. The mihrab marks the location of the prayer leader, who, at the Friday prayers of the time, was often the caliph (Fig. 1, 3, 6).

The “Minaret of the Bride” on the opposite side of the courtyard next to the north gate, the “Minaret of Jesus” at the southeast corner of the prayer hall and the southwestern “Minaret of Qaytbay” were built in several construction phases at least dating back to the 3rd century AH / 9th century AD, the Abbasid period (Fig. 1). While the two first-mentioned mosque towers have a classical square shaft with differently shaped tops, the last-mentioned corner tower is octagonal. This minaret with its consistent style was for the last time rebuilt at the end of the 9th century AH / 15th century AD by the Mamluk Sultan Qaytbay.

Wall decorations with two zones of marble slabs and gold ground mosaics are among the characteristic decorative elements of the original building. This goes back to Byzantine influence. A few original and true-to-original portions were spared by the last devastating fire in 1893, in Ottoman times, further mosaics were later uncovered. Today, especially the interior of the prayer hall shows a decorative character, which has changed in essential details (Fig. 6, 7).

The glass mosaics on the dominating façade of the transept with its triangular pediment as well along the western hallway depict vegetal motifs and large-scale landscapes featuring gardens, rivers and buildings (Fig. 3, 8). In contrast to the Ancient Christian tradition, the depiction of living beings is avoided due to the religious context of the building. It is interesting to note that in the second half of the 7th century AH / 13th century AD this precious decorative technique was deliberately used in order to embellish the mausoleum of the first Mamluk sultan Baybars in the neighbouring Madrasa az-Zahiriyya in an appropriate manner.

The splendour and magnificence of the Great Umayyad Mosque of Damascus continues to impress and impact people until this day. It is regarded as the embodiment of Syria’s outstanding Muslim heritage and, in religious terms, as one of the most venerable Islamic houses of worship. In terms of architectural history, this monumental mosque with its broadly stretched prayer hall is of key importance, notably for the Syrian architectural region and the subsequent developments in Early Islamic hypostyle mosques including some of the most prominent Friday mosques in the southern Mediterranean as well as the Great Mosque of Cordoba built by the Umayyad rulers of al-Andalus (Muslim Spain and Portugal).

The Great Umayyad Mosque of Aleppo

The Great Umayyad Mosque of Aleppo (Fig. 2, 9, 10) was built only a short time after that of Damascus, around 96 AH / 715 AD. It may also be attributed to al-Walid I or to his successor Sulayman ibn ʿAbd al-Malik. In this case, part of the area of the Byzantine Cathedral of Saint Helena was chosen as the site. In the ancient city, this was presumably the location of the central public square, the Roman forum or the Hellenistic Greek agora. The original building is entirely lost. A later historical source claims that its decoration was based on the model of the Damascene mosque.

The present great mosque, measuring 77.75 x 105 m, is about half the size of the great mosque in Damascus. Most of it goes back to the construction and expansion works by the Zengid Sultan Nur ad-Din as well as building activities in the Ayyubid and, finally, Early Mamluk periods (between the second half of the 6th century AH / 12th century AD and the end of the 7th century AH / 13th century AD). The shrine is dedicated to the prophet Zakariya, father of the prophet Yahya (Fig. 11). Its contents were moved from the Maqam Ibrahim Mosque on the Citadel to the Umayyad Mosque by Sultan Baybars after the destruction of Aleppo by the Mongols in 658 AH / 1260 AD.

The prayer hall with three naves was given its last form in the course of reconstruction work by the Mamluk Sultan Qalawun, completed in 684 AH / 1285 AD. All columns were replaced by pillars. Today, between four rows of 20 square pillars span cross vaults (Fig. 10). Thus, visitors get the impression of a homogenous, though rather squat space, which appears solemn due to the low incidence of light. Only the aisle between the entrance portal and the main prayer niche is slightly wider than the others and is marked by a dome (Fig. 9, 12).

Overall, the impressive stone architecture, whose decoration with stone inlays and reliefs is limited to major building elements, bears a sober character (Fig. 9–12). Following the model of this vaulted prayer hall, important Friday mosques in Aleppo and other cities in the western Syrian architectural landscape were rebuilt or redesigned. Pillars and cross-vaulted ceilings are also typical elements of the medieval Crusader architecture of Syria and the eastern Mediterranean.

The square-shaped, 45-metre-high minaret of the Great Mosque collapsed in 2013 (Fig. 2, 14). It was the oldest and largest remaining part of the building and dated back to the 480s AH / 1090s AD, to the Seljuk period. This minaret was commissioned by the influential judge of Aleppo, the qadi Ibn al-Khashshab, from the local architect as-Sarmani. Its characteristic multi-zone decoration reflects the arch-shaped circumferential profile bands of the Late Antique-Early Byzantine architectural tradition in northern Syria together with Islamic design elements such as inscription bands. It set the style for other minarets.

This masterpiece of minaret architecture, which had towered over the mosque and the adjacent central market area, Suq al-Madina, for over 900 years, will continue to serve the city as a famous landmark: a complete reconstruction of the Great Umayyad Mosque of Aleppo is in progress (Fig. 13).

Featured image: View over the roof of the south-western Madrasat Ismaʿil Basha al-ʿAzm to the Great Umayyad Mosque of Damascus with its high transept of the prayer hall with a central dome and its three minarets (1985) | Museum für Islamische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Collection Eugen Wirth (CC-BY-NC-SA)

Published by Eva Nmeir: Art historian with special reference to Syria. She worked for the Syrian Heritage Archive Project and its co-projects on the World Heritage sites “Ancient City of Aleppo” and “Ancient Villages of Northern Syria”, among others.