by Dr. Saria Almarzook

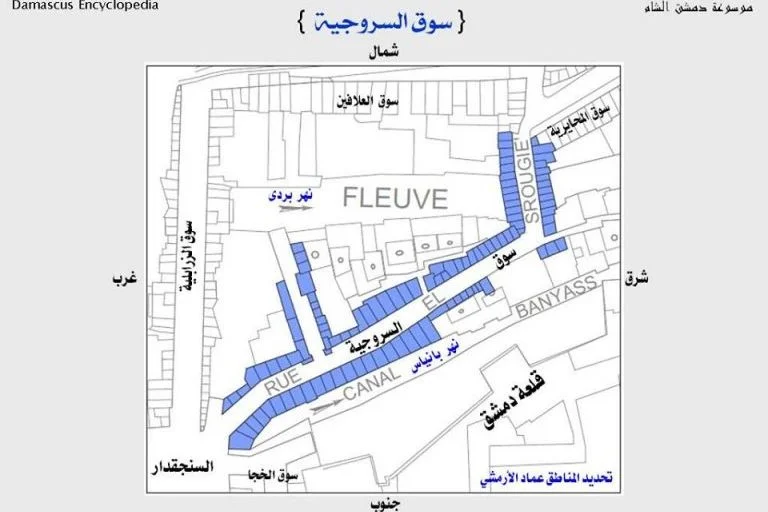

In Damascus, the oldest capital in the world with one hundred and fifty markets (suq), it is still possible to see the “ruins” of the famous as-Surujiyya Suq. The market lies to the north of the al-Hamidiyya Souq and the al-Khaja Suq, bordering the walls of the historic Citadel of Damascus at its western or the gate of the Secret, and overlooking the banks of the Banias and Barada rivers, opposite the as-Sanjaqdar Mosque (Ibn Mabrid, 1939). as-Surujiyya Suq was perpendicular, at its western side, to the Zarabiliyya Suq (before it was demolished). To the east, it was bordered by traditional courtyard houses and the al-Mahayariyya Suq; and by King Faisal Bin Hussein Street to the north (Nuaisa, 1986). The remaining market extends, with an arched iron and zinc roof, from at-Thawra Street and King Faisal Street parallel to the wall of the Citadel of Damascus, shown on the map of as-Surujiyya Suq and its surrounding areas (Fig. 2).

As-Surujiyya Suq was most probably established in the Ayyubid period, around 800 years ago. The suq specialised in the manufacture of saddles for horses, for all other types of animals used for transportation on trade routes and those used in fields and for other services, such as mules, donkeys and camels (Al-Armashi, 2017). The demand for horse saddles increased with the arrival of the Ottomans in Damascus and their involvement in military campaigns. There was a need to equip horses at military camps and barracks. Saddles were also needed by travellers and so-called ‘Orientalist explorers’ who toured Ottoman states in different eras, particularly during the end of Ottoman rule in the Levant, at the end of the nineteenth century and the turn of the twentieth century. Everyone wanted Arabian saddles made in Damascus’ as-Surujiyya Suq (Nuaisa, 1986). The limited references available do not state, that the manufacture of saddles was exclusive to Damascus as-Surujiyya Suq; some breeders mention that there were local saddle manufacturers in the countryside and towns far away from Damascus. However, the cavalry took pride in using Damascene saddles and considered them essential decorative features at major events and festivals combining beauty, quality and sturdiness.

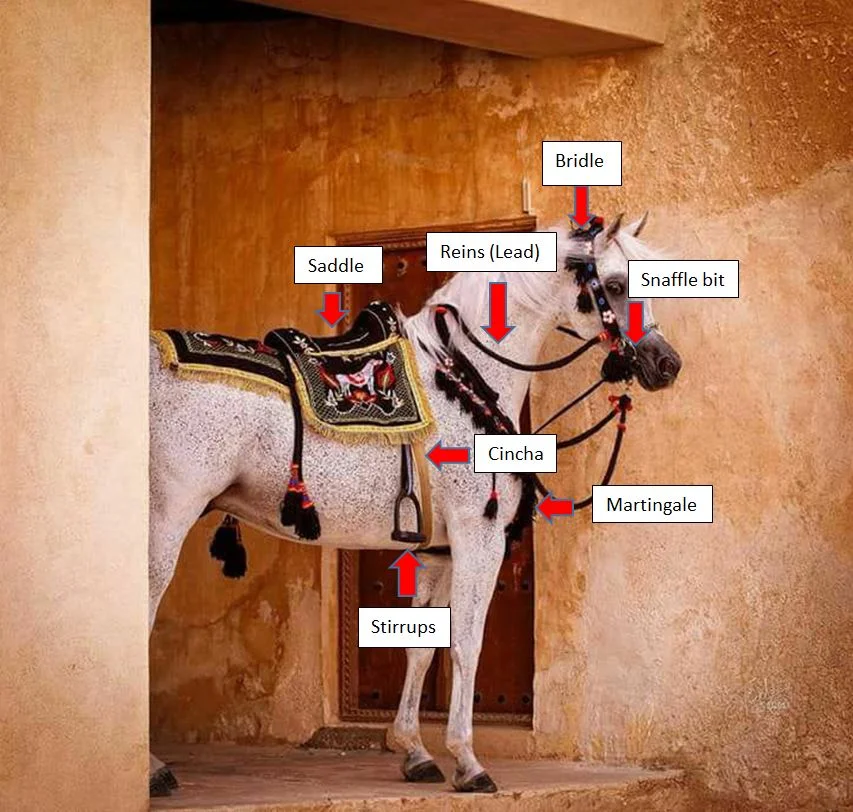

Surujiyya refers to saddle making tools and the production of saddle equipment for horse riders. Essential elements of this equipment are the saddle (or jalal, the covering on the horse’s back) and its accessories including bridle (الراسيات), reins or lead (الصرع أو المقود), snafflebit (الشكيمة), Belly Band Billet or Cincha (الحزام), Martingale or breast collar made of threads and shells (الشوبند أو الصدرية) or a Martingale made of silver (السلبند), and lastly the stirrups (الركاب).

The saddle seat is made of a mat that is sewn on all sides (الجلال). It originally used to be stuffed with straw, chosen for its light weight. Later, it was stuffed with cotton and extra pieces of cloth, covered in leather and then with embroidered fabric, which ensures the rider will feel comfortable while riding a horse with an Arabian saddle however long the journey. Saddles are made from the best types of baize, cotton and wool. Equestrians in Damascus, and more generally in Syria, use different names depending on whether the saddle seat is long (marshaha) and extends to cover the whole of the horse’s back up to its tail or is short (kafliyya). The hand worked inscriptions vary on the saddle, which is adorned with silver and colourful woollen threads. The saddle accessories, along with the saddle seat, form are a complete design covering the body of the horse. It guarantees total comfort for the horse and the riders, with all the visible displays of prosperity: the amount of silver amulets, precious stones, shells and colourful beads that embellish the bridles and martingale in particular (see Fig. 4 and 6).

The saddle is usually reconditioned for festivals or shortly before travel, according to the customs of the Syrian people, who see a good omen in preparing the horse. Because of this reason, the status of the horse and welfare of the riders is honoured and blessed on religious holidays or when departing for business or the Hajj (Sheik Al-Sroujieh, 2019). This is mainly due to the religious status of Arabian horses in Islamic history and their mention in the Qur’an (The War Horses – Al-‘Adiyat, Chapter 100) and prophetic traditions.

It is believed that the organization of the craft goes back to the Fatimid era (10th – 12th century), however its characteristics were further defined in the Ottoman period when each profession in Damascus had a master craftsman (Sheikh Al-Kar). According to historical references, there were 435 craftsmen (Kar) registered in Damascus at that time (Al-Qasimi and Al-Azam, 1988). Kar is a Persian-Turkish word which means trade. It was used in the Ottoman period to refer to craftsmen of the same profession. Each group of craftsmen was headed by a master craftsman, usually from a noble family (prominent families from Damascus or a family whose lineage can be drawn back to the family of the Prophet Muhammad) or Janissaries (who belonged to the strongest divisions of the Ottoman army and were considered personal guards of the Ottoman sultans) (Farid Beg, 1981). The master craftsman can be equated to the head of a professional guild, appointed through a deed issued by a judge and registered in accordance with the law in the records of the Damascus court (Nuaisa, 1986).

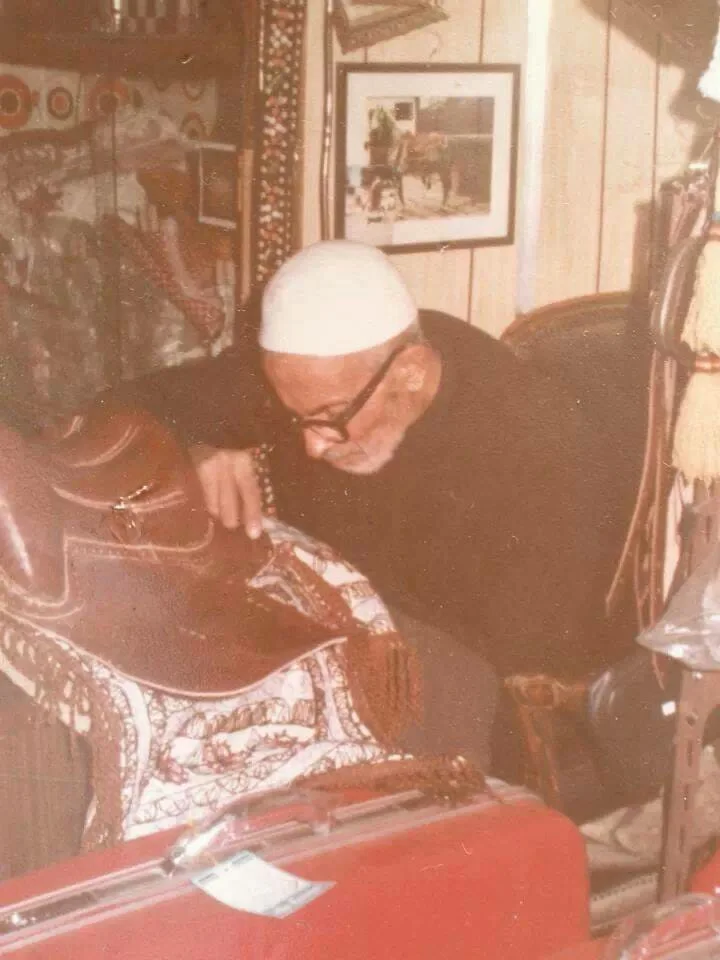

Damascene Arabian saddle manufacture is considered a traditional craft, which combines a legacy of the knowledge and skill necessary to produce a saddle and its accessories, identify the necessary instruments and know the terms used to describe the activities and products of this craft. Unfortunately, the number of craftsmen has fallen and there is currently only one craftsman.

The story of the As-Surujiyya’s last master craftsman: Khalil Ibrahim Sheik Al-Sroujieh

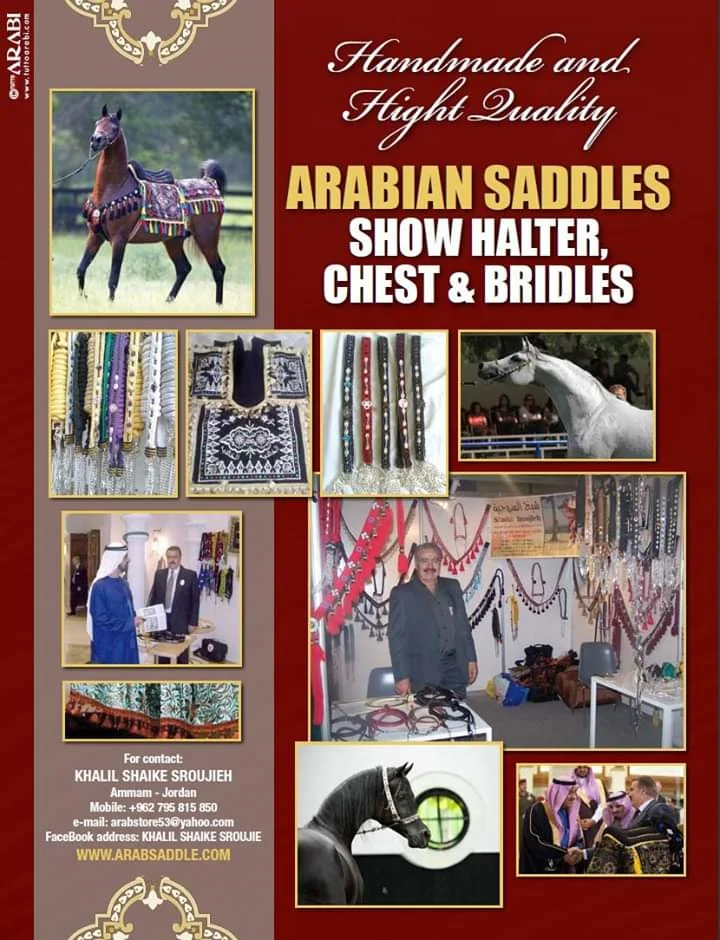

With the spread of modern means of transport and the disappearance of horses from public life, the functional and professional purpose of the As-Surujiyya Suq faded away. Most of the skilled saddle manufacturers left the country, taking the secrets of the old trade with them. However, horse breeders (in particular, of Arabian horses) in all parts of the world still want to buy Arabian saddles and accessories, even if the aim is solely to decorate their horses for events or photo shoots or to hang them on the walls of their houses and guesthouses as traditional decorative items.

Khalil Sheik Al-Sroujieh says, “the people working in saddle manufacturing were called “suruji” (from the Arabic word for saddle, suruj). When there were any disputes or problems, a person with experience, intelligence and tact would be chosen to deal with it. Above all, he had to have the financial capacity, piety and personality to solve the traders’ problems. The governor of Damascus issued a decree on the need for each profession to have an official or master to find appropriate solutions to problems in the market or among the craftsmen. This person was called the master craftsman (Sheikh Al-Kar). As our family was the best able and of longest standing in this trade, our forefather was chosen as a master for this profession at the end of the eighteenth century. The craft was passed down through the family and the title of Sheikh Al-Kar has remained in the family. This professional title has eclipsed our surname so that the family now has the surname of Sheik Al-Sroujieh.”

Khalil son of Ibrahim son of Ahmed son of Amin son of Muhammed Said Sheikh As-Surujiyya is the chief of the saddle manufacturing craft today and the last master craftsman. This title was also held by his paternal grandfather (Sheikh Muhammad Said, known as Abu Amin), a senior expert in the profession and the representative of saddle manufacturing workers to other professions and the head master craftsman as well as its representative to the Ottoman state. His powers included the ability to grant (or withdraw) a license to practice the profession, under a decree issued in 1797 (military division record no. 330, afterwards Damascus High Court record no. 240). The craftsmen usually inherited the position of master craftsmen from their fathers or brothers. They were changed if they were discharged through a decree from the sultan calling for the appointment of a new master craftsman and setting out the qualities sought. The As-Surujiyya Suq did not only specialise at that time in saddle manufacture; it was also a centre for the production of cases for pistols and small rifles as well as covers to protect books and amulets (Al-Dimashqi, 1341H).

Khalil relives memories of his childhood and youth in Damascus’ as-Surujiyya Suq and the loss of more than 14 of the family’s shops through the demolition of a vital part of the suq in 1970. Fortunately, his father Ibrahim Sheik Al-Sroujieh had moved a part of his equipment to Amman, Jordan, and settled there with his family. He opened a shop manufacturing saddles in al-Hashimi Street (Rashid, 2002). Khalil Ibrahim Sheik Al-Sroujieh still runs his shop in Amman with his brothers and sons, maintaining the family tradition and the craft of their forefathers. He also still visits Damascus from time to time for supplies of fabrics, braided rope and raw materials that are only available in Damascus. Khalil talks about the stages of making an Arabian saddle, “the model is made out of jute and is stuffed with cotton or wool. The stirrups are then attached, on the left and right, and a strap for the stomach of the horse (from the right side). Two wooden pieces, called ka’ka in the trade, are then fastened at the front and back, the front is covered with baize or tadriba (stitching of the saddle seat with a long needle and two braided woollen threads and the corners in a shape parallel to the horse’s back) after the filling has been placed and its thickness checked to ensure the comfort of the horse and the riders. After the stirrups and the lower saddle strap have been fixed, the accessories, which include the chest strap, halter, tether and lead are set in place. The production of one saddle takes three or four days of continuous work”.

Khalil goes on saying, “the purchase of horses is now limited to the rich, sheikhs, princes and their studs. They spare no expense in purchasing the best Arabian saddles. Their demand for riding saddles might even include golden elements for the purpose of only displaying an image of an industry that is on the verge of disappearance. There are only a handful of craftsmen today. Recently, there have been some light and cheap saddles that people use to ride horses in parks, resorts and archaeological sites but they are undoubtedly incomparable to the original saddles”.

We are now more than ever before aware of the importance of conserving traditional craft industries and the need to document skills and conserve their details and changes without losing knowledge of them or losing the terms and words associated with them over time. In recent years, handcrafts are increasingly in decline, particularly with advance of technology in manufacturing and loss of appreciation for traditional industries, along with interest in the details limited only to breeders with financial resources. Khalil Ibrahim Sheik Al-Sroujieh receives invitations from equestrian gatherings around the world to present his hand-made products. Specialized international periodicals interested in equestrian heritage publish articles about him and oriental saddle-making craftsmanship continually. There are, however, major challenges this traditional craft faces. The main one perhaps is that the craftsmen need suitable permanent market outlets to distribute their products, cover the labour costs and make reasonable profits for them so that it can be passed down to future generations.

Dr. Saria Almarzook, Syrian-German associated lecturer and translator. She holds a PhD in Molecular Biology and Biodiversity of horses from the Humboldt University of Berlin. Her book on diversity of horses (ISBN: 9783895749476) was published in 2018. Furthermore, her articles are published in peer-reviewed scientific journals like Animal Genetics.

I want to know complete history about sarraj ( saddle maker) . I want him family tree and i want which tribe start saddle makker in arab

Hello Zia,

you are right. Sarraj refers to the occupation of saddle making. We don’t have documents such as family trees in our collections, and as far as we know there is no central archive that keeps them. Such documents are usually kept by individual families as part of their heritage. Your best chance is to contact members of the Sarraj family. Good luck.

Oh, wow! What a great explanation. When you said that certain horse saddles are hand-stitched and take months to complete, it really blew my mind away. My ultra-rich uncle just bought a horse ranch in the countryside last month and he’s inviting me for a ride next weekend. I’ll make sure he reads this article so he’ll get some proper equipment for the activity soon.