by Ruwaida Tinawi and Hiba Bizreh

“Bathing is a bliss of life” is a saying that my mother always repeated while bathing in order to entice my brother and me as children to take a bath. I am sure that my mother adopted this pictorial saying from her Turkish mother, who at the beginning of the 20th century – both in Turkey and in Damascus – had never visited a hammam other than the public one. My grandmother summarized in this saying all the joys of life at that time: going out with daughters and neighbours, the feeling of cleanliness and – probably most importantly – the “ladies’ reception” in the hammam, with dancing, singing and banquet.

The hammam’s visit was not limited to a particular stratum of the population, because it is a social place for everyone – rich and poor. Often it was also an important station for the rural population who came to the city to do errands and other duties. In addition to its hygienic role, it also had an important function as a place to relax from the strenuous journey.

The idea of the public bath goes back to the Greeks in the 5th century before our time. It then spread through the Seleucids and Romans, whose hammams were characterized by an imposing architecture. Syria was known in Roman times for its hammams.

A bath consisted of several parts: the changing room, the cold bathing area, the warm bathing area and the hot bathing area. Examples of Roman baths can be found in Palmyra, Bosra, Sirjilla and Shahba. The tradition was then continued by the Muslims, who built hammams in all cities with their own architectural and artistic styles. These baths also had a very special social function.

There were two types: the public ones, which were run independently, and the ones that were integrated into the palaces and bimaristans (hospitals).

The Islamic hammam usually consists of four areas, all of which are covered by domes:

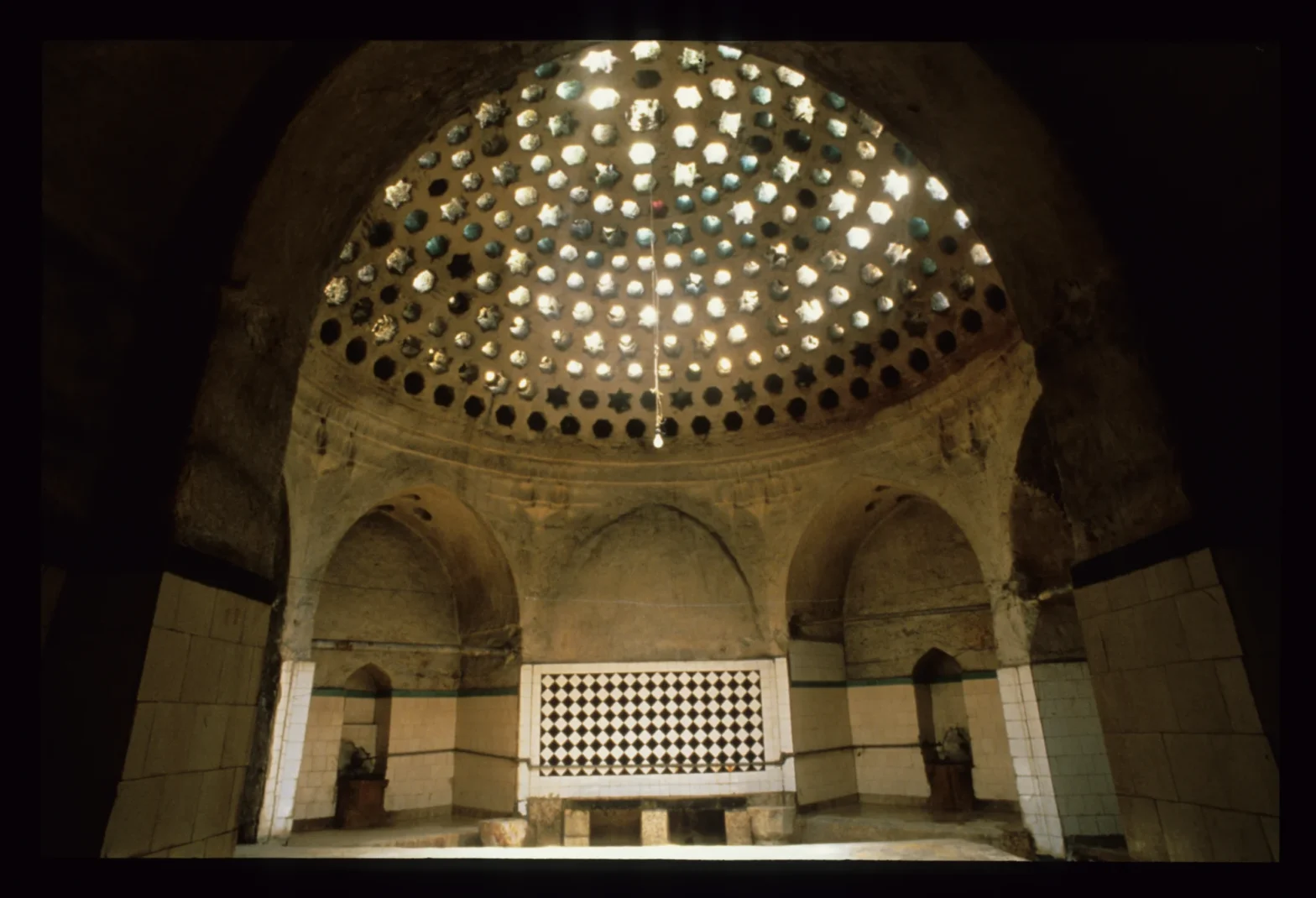

In the so-called ‘outer area’ (al-barrani) people changed their clothes. The hall, which was provided with a central well, was also a place for get-togethers, entertainment and exchange, even business transactions. For ladies it was also a popular place for festive occasions such as marriage and birth. Through this area one reached the next, the middle area (al-wastani). In this area the temperature is mild. The third area is called the ‘interior area’ (al-juwwani). It is the hottest room of the bath. The floor is covered with coloured marble slabs, the small domes that cover the room are interspersed with glass stones. Adjacent to the interior is the place of water heating (al-qamim), from where the water is fed directly into the juwwani. The last room of the hammam is a room for the heater (al-qamimi), who is responsible for constantly supplying the stove with combustible.

In Damascus, most public hammams were located within the old town and near the city gates, mosques and schools. So it is at the Hammam al-Malik az-Zahir, which bordered on az-Zahiriyya School. In addition, hammams were installed in the market areas near the accommodations to serve the traders and travelers, such as Hammam Nur ad-Din ash-Shahid in the Buzuriyya Market. As a result of the expansion of the city beyond the city wall in Ayyubid times, the hammams were built in the northern quarter along the Tura tributary, where we find five hammams, some of which are still in operation, such as the Hammam Ammuna.

One of the most famous Mamluk hammams outside Damascus’ city wall is the al-Qaramani Hammam near Marja Square and are the Hammams in the suburb of Salihiyyat Dimashq, like Hammam al-Muqaddam and Hammam ʿAbd al-Basit. Hammam at-Tayruzi (at-Tawrizi) is also considered one of the most important hammams of Damascus. It was built by the Mamluk prince at-Tawrizi as part of a building complex that included a mosque with his tomb. Hammam Fathi in the Midan district is a special example of Ottoman architecture in Damascus due to the rich ornamentation of its façade.

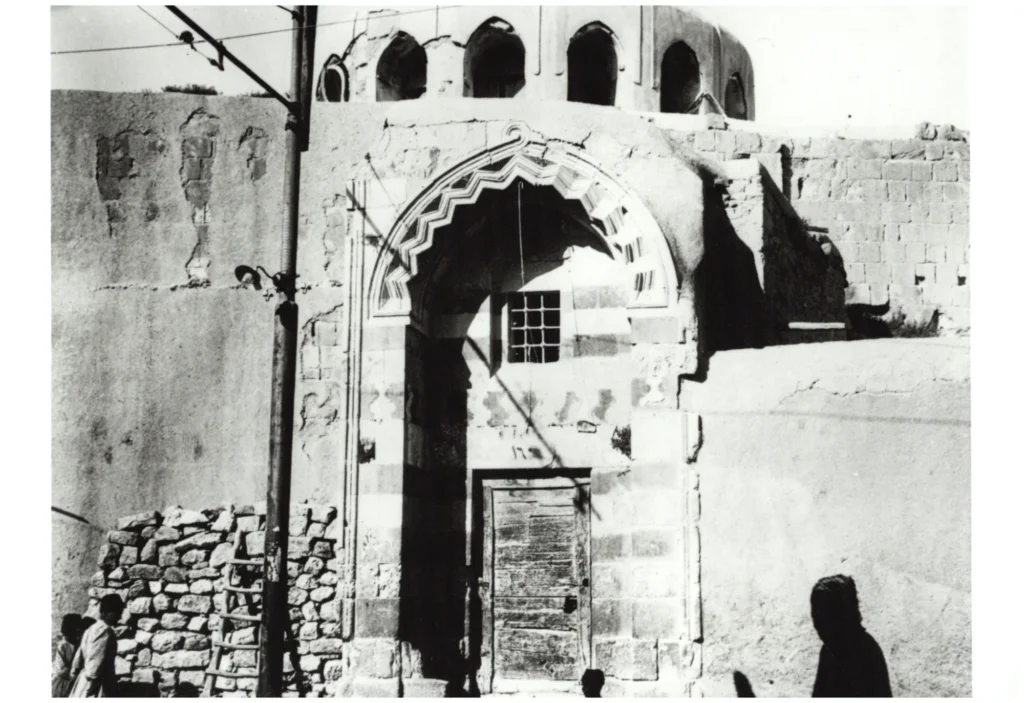

The Aleppine people have added a new element to the public bathing culture: laurel soap, which has long enjoyed a unique fame all over the world. Aleppo also adapted architectural styles known from Istanbul and Anatolia. The Hammam an-Nahhasin is considered to be the most famous of the Ayyubid period, characterized by a dome decorated with glass light apertures. Unfortunately, this hammam was damaged in the last years of the Syrian crisis. Among the Mamluk hammams, the hammam Yalbugha an-Nasiri, which is considered to be one of the most beautiful Islamic hammams of Aleppo, should be mentioned above all. It has an impressive façade with an alternation of yellow and black stones. The high entrance, decorated with Mamluk blasons, is framed on both sides by windows. Like many other Aleppine ‘architectural treasures’, this hammam was largely destroyed during the last war. The Hammam Bahram Basha shows a development of the hammam building of the Ottoman period in Aleppo. Its northern façade opens outwards, also characterized by the typical alternation of yellow and black stones (ablaq).

Most Syrian cities have public hammams. Especially famous is the Hammam as-Sultan in Hama, the Hammam at-Tasawir in Jabla as well as the Hammam al-Basha and the Hammam al-ʿUthmaniyya in Homs. The latter was recently restored and put back into operation. In Bosra, the Mamluk Hammam al-Manjak is particularly well known. It was restored in the 80s of the last century by the Syrian Department of Antiquities together with the German Archaeological Institute and now houses the Islamic Museum. The Mamluk hammam in as-Salamiyya is also a typical example of the Syrian hammams and can be seen from afar through its domes, which are slightly pointed towards the top.

Many of the public Islamic hammams of Syrian cities have disappeared completely. Others are still standing, but have lost their function as hammams and turned into shops or workshops. Fortunately, some have been preserved and restored, such as Hammam al-Qaramani and Hammam Ammuna in Damascus.

For some time now more and more Syrians have been visiting public hammams to preserve traditions and customs and to remind people of the traditions of their ancestors, but also to forget the harsh conditions of the war in a place of bliss. Just like the cultural-historical background of the Hammam building, the words of our ancestors are rooted in the collective memory. Whatever the local and temporal changes and whatever the changing living conditions, I never see the hammam – both public and private – differently than the joys of life.