by Hiba Bizreh

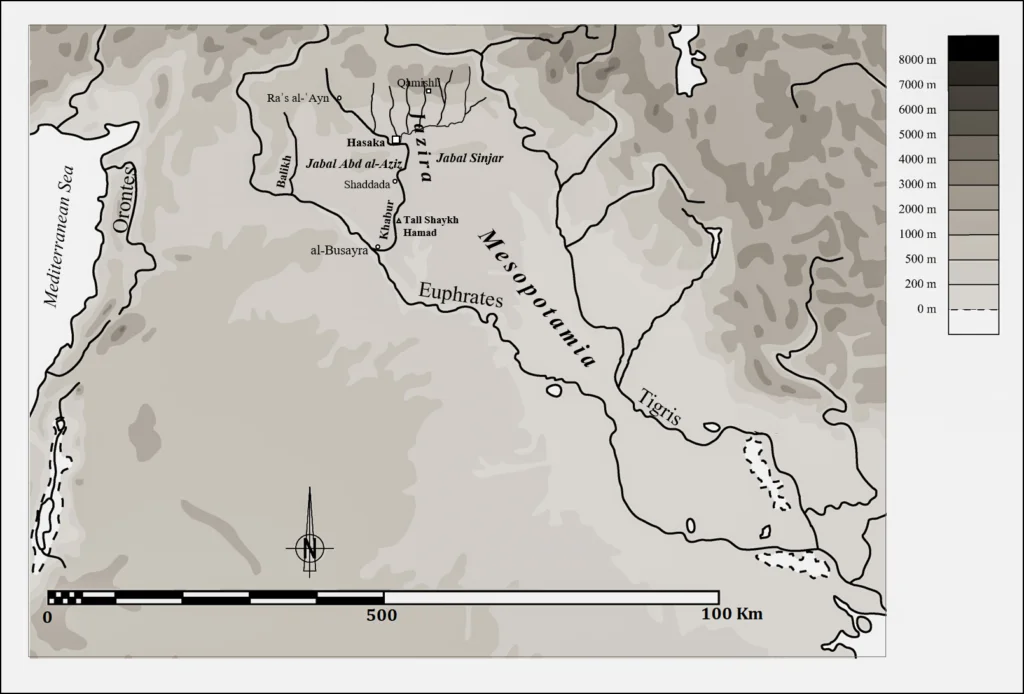

The vast region of northern Mesopotamia („land between the rivers” in ancient greek) stretches from the Euphrates to the Tigris. Even in our times, the local name refers to the specific geography: it is called in Arabic “al-Jazira” meaning „the island”. The region includes the floodplains of the Euphrates and its two main tributaries, the Khabur and the Balikh, and today it forms the north-east of Syria.

Two smaller mountain ranges – Jabal ʿAbd al-ʿAziz and Jabal Sinjar – form a natural limitation between the fertile Upper Jazira in the north, and the Lower Jazira in the south with its partly barren soils.

The annual rainfall of about 300 mm and more (close to the eastern Taurus foothills) allows for dry farming in the Upper Jazira, which is represented by all sorts of grains, especially wheat, while the rain-scarce southern parts depend on irrigated agriculture, in particular cotton cultivation. Besides farming, grazing of sheep, goats and cows is an important factor in Jazira life in general.

The Khabur River is the main nerve of the Jazira region. Its shallow region consists of vast steppes and plains that include many archaeological mounds, which are situated especially near waterways. They testify to human occupation in the region since prehistoric times.

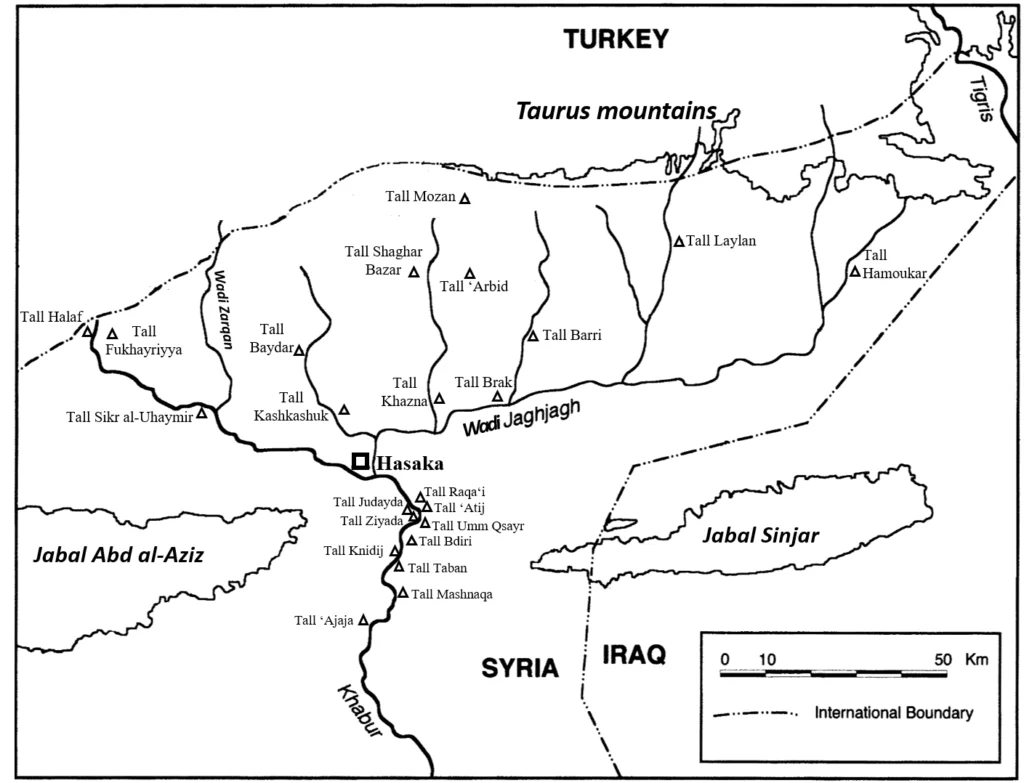

The northern part of the Khabur region has a triangular shape called “Khabur Triangle” or “Upper Khabur.” The modern city of al-Hasaka is located in the southern angle of the triangle that embraces many villages and cities, such as Raʾs al-ʿAyn and al-Qamishli. Several wadis flow in this region and converge to finally pour into the Khabur. Despite their dryness in the summer, they return to life in spring thanks to the winter rains in the northern, mountainous region of Tur ʿAbdin (a foothill to Taurus mountains) and nowadays part of modern Turkey.

The Middle Khabur Basin extends from al-Hasaka to the town of Shaddada; from here to al-Bsira (al-Busayra), where the Khabur meets the Euphrates, extends the Lower Khabur Basin.

The richness of archaeological remains in the Khabur region has attracted archaeologists and travellers since the 19th century. The first discovery in the Lower Khabur began in 1850 with a few short excavations carried out by Austen Henry Layard. In 1893, the German Diplomat Max von Oppenheim (see article “The Donkey Guide of Max von Oppenheim“) travelled in the region and described some sites on the Khabur banks during his passage through this area.

In 1907/08 Ernst Herzfeld and Friedrich Sarre surveyed the region and described many of the river’s west side ancient oriental mounds (Talls). The first comprehensive surveys, especially for the Lower Khabur region and some sites south of Hasaka, were carried out in 1975 and 1977 by the “Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orient” (TAVO) collaborative research team. They could identify 55 sites; most of them date to different periods of the ancient Near East, especially the Bronze Age (3000–1200 BC), like for example Tall ʿAjaja, Tall Taban and Tall Shaykh Hamad. At Tall Shaykh Hamad/ Dur Katlimmu a German team from the Free University of Berlin under the direction of Hartmut Kühne excavated systematically since 1978, and have recovered 550 cuneiform Akkadian and 40 Aramaic texts.

Following the international appeal launched by the Directorate-General of Syrian Antiquities and Museums to safeguard the archaeological sites located in the Khabur region from the threat of the waters of three dams near Hasaka, a French team under the direction of Jean-Yves Monchambert started in 1983 a systematic survey of the sites found in the area of the future lakes. The French team identified 58 historic sites, like for example Tall Umm Qsayr (Qseir)[1], Tall Ziyada[2] and Tall Raqa‘i. The latter was excavated by a Dutch-American joint mission headed by Glenn Schwartz and Hans Curvers.

Subsequent excavations at some of these sites indicated that they contained archaeological layers, the earliest of which date from the Halaf period and the latest from the Islamic periods, passing through the Ubaid period (5000 -3800 BC), the Uruk culture (3800 -3100 BC), the Bronze Age and the classical periods.

Tall Mashnaqa in the Middle Khabur is classified among the most important sites that were excavated by J.-Y. Monchambert between 1985 and 1986. Subsequently, another French team led by Dominique Beyer took over the excavations between 1992 and 2000. Before Tall Mashnaqa was submerged by the waters of the dam lake reservoir, D. Beyer was able to carry out extensive excavations, which proved that Mashnaqa is the only tall – so far – in the Middle Khabur region that shows a continuity of human settlement from the 5th millennium BC (Ubaid period) to the 3rd millennium BC, as well as a more recent settlement dating back to the Roman period. However, the 4th millennium BC levels, or the so-called Uruk civilization, yielded the most important finds at the site, namely tripartite houses, ovens and kilns, and a round huge building which would have been defensive.

Several other foreign missions responded to the call of the Directorate-General of Syrian Antiquities and Museums, including Laval University in Canada, which began rescue excavations in two sites in the Middle Khabur: Tall ‘Atij (eastern river bank) and Tall Judayda (Gudayda) (western river bank), about 19 km south of Hasaka. The systematic excavations into both sites were carried out by Michel Fortin from 1986 until 1993. He could reveal several buildings dating back to the Early Bronze Age (first half of the 3rd millennium) especially in Tall ‘Atij, where the Canadian mission discovered a kind of commercial station provided with multiple storage devices intended to store various products but in particular grain.

A few kilometres south of Tall ‘Atij lies Tall Bdiri, which during the Early Bronze Age was an important centre in the Middle Khabur region, with an area of 6 ha. Excavations at the site began in 1985 and continued until 1992 by a German mission led by Peter Pfälzner.

Archaeological excavations and surveys have not been limited to the Middle and Lower Khabur Basin, but foreign and national missions have played a major role in the study of large areas of the Upper Khabur. This region includes many important cities in the ancient history of the Near East, such as Tall Brak/Nagar, which is located on the banks of the Jaghjagh-wadi. This site consists of several mounds, the largest of which covers 43 ha. Excavations at Tall Brak began in the 1930s by a British expedition led by Max Mallowan; many British archaeologists continued the work until 2011. Tall Brak is one of the world’s earliest cities, reaching urban scale and complexity by the early 4th millennium BC and retaining political importance and economic power through most of the 3rd millennium BC. The main mound bears witness to human settlement from the beginning of the 6th millennium BC (Halaf period) to the end of the 2nd millennium BC (Late Bronze Age or Middle Assyrian period). There is no doubt that the most famous building of the Urukian period in Brak is the “Eye Temple,” whereas the palace of Naram Sin, the Akkadian king, is the most prominent building of the 3rd millennium BC.

![Tall Brak (Nagar), ruins of Naram-Sin Palace, 3rd millennuim BC. [Original photo name: naram sin palace2]](https://syrian-heritage.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/shap_import_44762.webp)

More than 60 years after the beginning of excavations at Tall Brak, archaeologists discovered a new site whose architectural remains and pottery have proven the existence of a city that rivalled Nagar in terms of development and urbanization in the 4th millennium BC. It is Tall Hamoukar, located at the eastern end of the Khabur triangle, close to the recent Iraqian border. This site has been studied since 1999 by a team from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, in partnership with a Syrian team. The prosperity of the city of Hamoukar is marked by the development of an urban and local social system that gives the best example of a city in northern Mesopotamia during the Uruk period.

On the Wadi Da‘a in the upper Khabur, is located Tall Shaghar Bazar (Chagar Bazar), which was excavated first by Max Mallowan, accompanied by his wife, Agatha Christie, from 1935 to 1937. Work was resumed at the site in 1999 by an expedition from the British School of Archaeology, in cooperation with archaeologists from the University of Liège and the Syrian Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums. The excavations revealed an important settlement dating back to the Halaf period (6th millennium BC) through the discovery of mostly geometrical painted pottery and figurines of naked women representing fertility. The site was occupied almost without interruption until the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC and was re-settled in the Middle Bronze Age (2004-1595 BC). In the 18th century BC, Chagar Bazar was one of the most important cities of the Assyrian Empire. An important building, perhaps of palatial type, was partially excavated, and yielded cuneiform administrative tablets (more than 300). The site was completely abandoned in the middle of the 2nd millennium BC.

Near Tall Brak is the site of Tall Baydar (Beydar), the ancient city of Nabada on the banks of Wadi Awaij (Aweij). Inscriptions found in the site indicate that in 2452 BC, Nabada was an important city belonging to the Nagar kingdom of Tall Brak. The main occupation of Baydar dates back to the 3rd millennium BC, and because of its importance, a joint European-Syrian mission conducted 16 seasons of excavations between 1992 and 2010. The topography of the site consists of a circular city, protected by perimetral fortifications with seven gates. The site was partially reoccupied in the Hellenistic period.

In the late 1970s, a Dutch mission led by Diederik Meijer explored a large part of the Khabur Triangle, which yielded information on sites dating from several periods, from the Neolithic to the Islamic era. Around the same time, a mission from Yale University conducted surveys and investigations in the Tall Laylan (Leilan) area, which uncovered sites from the most important periods of the ancient Near East, including the Ubaid, Uruk and Bronze Age.

Russian archaeologists played also an important role in excavating one of the sites of the Upper Khabur: Tall Khazna is located about 25 km north of Hasaka, on the left bank of Wadi Khanzir. From 1988 to 2000, the Russian team, under the supervision of Rauf M. Munchaev, carried out excavations that revealed distinctive architectural buildings extending from a transitional period between the final Obaid and the beginning of Uruk, until the 3rd millennium BC.

The exploration of the Upper Khabur was continued between 1989 and 1991 by a French mission led by Bertille Lyonnet. The aim of this campaign was to shed light on the geoarchaeological evolution of this region during the 2nd millennium BC. However, due to the archaeological wealth that encompasses different periods of the ancient Near East, the mission attempted to reconstruct both the history of the sites and the evolution of the environment in the Upper Khabur. Lyonnet’s survey covered 64 sites, including some from the Pre-Pottery and Pottery Neolithic (8300–5600 BC) such as Tall al-Fukhayriyya (al-Fakhriyya) and Sikr al-Uhaymir. The mission also collected painted Halaf pottery (5600-5000 BC) from 40 sites.

These surveys of Halafian sites add strong evidence that the Upper Khabur was a densely populated area during the Halaf period, and it is possible that the region played an important role in the Halafian world. A Japanese expedition discovered in 1985 at Tall Kashkashuk important archaeological remains dating to the Halaf culture.

However, the site from which this culture took its name is Tall Halaf. This site on the Khabur River directly on the recent Syrian-Turkish border, was discovered by the German diplomat and archaeologist Max von Oppenheim in 1893. From 1911 onwards he conducted extensive excavations which confirmed that the site had been inhabited since the 6th millennium BC without interruption and became a prosperous settlement in the 5th millennium. The site was subsequently abandoned for a long period until the beginning of the 1st millennium BC, when the Arameans founded the kingdom of Guzana. It survived during the collapse of the Assyrian Empire and continued to be inhabited during the Roman-Parthian period.

In addition to the above-mentioned sites, there are many major sites in the Upper Khabur Basin, which testify to the great importance of the region in the history of the ancient Near East, such as Tall Barri, excavated since 1980 by a joint Italian-Syrian mission led by Emilio Pecorella, as well as Tall ‘Arbid, which has yielded important finds dating back to the 3rd millennium BC. The excavations were conducted by a Polish-Syrian mission under the direction of Piotr Bieliński.

The ancient town of Urkesh (Tall Mozan) is one of the cities that participated in the overall political development of northern Mesopotamia from the 4th millennium to the last part of the 2nd millennium BC. The peak of the city’s development was in the Akkadian period (3rd millennium BC). Excavations have revealed several buildings, the most important of which are the temple of Kumarbi (2400 BC) and the ancient royal palace (2300 BC). It should be noted that Tall Mozan has been excavated since 1984 by a joint American-Syrian mission led by Giorgio Buccellati. They initiated an eco-archeological park and a project for traditional handicraft goods, which are made by women in the villages of the region.

Archaeological fieldwork and important discoveries in the Syrian Jazira over a period of more than a century have proven that Northern Mesopotamia – like Southern Mesopotamia – has been a scene of cultural, social and political development since the end of the 5th millennium BC and a cradle for the first centers of northern civilization.

The rescue excavations and the documentation of the most important sites in the Khabur-Basin brought a huge pool of knowledge, but a large number of these Talls, which revealed these information, were completely submerged by the waters of three lakes of the “Khabur al-Kabir Basin Irrigation Project”. The Khabur-West, Hasaka-West, Hasaka-East reservoirs flooded a large part of these historic mounds. Among the lost sites are Tall Mashnaqa, Tall Ziyada, Tall Knaydij (Knedij), Tall Taban and Tall Bdiri. Unfortunately, other sites were inundated by the waters before the hand of the excavators reached them, drowning along with them their history, of which we only have the brief information through the surveys. Despite this great loss, the richness of the Jazira in archaeological remains gives cause for optimism, as many other sites can hopefully provide us with new knowledge in future about the civilizations and cultures of the ancient Near East.

Featured image: Tall Baydar, Temple B – decorated wall and low bench inside the central espace, 2010 | Hiba Bizreh (CC-BY-NC-ND)

[1] A systematic excavation at Tall Umm Qsayr (Qseir) (25 km south of Hasaka) was carried out in 1986 by Frank Hole from Yale University.

[2] Located on the right bank of the Khabur, about 14 km south east of Hasaka, the Tall was excavated between 1988 and 1990 under the direction of Georgio Buccellati from the University of California. Then in 1996 and 1997, a team of Yale University directed by Frank Hole took over the excavation work.

Published by Hiba Bizreh: Hiba Bizreh is an archaeologist working for the Syrian Heritage Archive Project since 2018. She received her PhD from the University of Strasbourg (France) in 2015. Her doctoral thesis “Research on the proto-urban period in the region of Khabur” focused on Tall Mashnaqa, the site which is characterized by a continuity of human settlement from the 5th (Ubaid period) to the 3rd millennium BC.